It is often overlooked that the Whitney Biennial is a group exhibition. This, perhaps, is due to the effects a biennial selection can have on the career of an artist—as the exhibition showcases less-well-known creators, its list of artists serves as a powerful hot-or-not roster for the contemporary moment (a point of considerable interest to aficionados and investors alike). With this in mind, and considering the Recession Special of a scaled-back field—the 2010 biennial includes only 55 artists, a considerable reduction from the 81 and 100 presented in its two most recent iterations—I expected that the ordained individualism would be amplified, as the Lucky Few fought over unprecedented shares of acclaim and artist-specific attention. Instead, I discovered an exhibition described by a sensibility of nearly-singular focus. With an unprecedentedly collective spirit, the artists of the 2010 Whitney Biennial—whose works will remain on display through May 30th—reignite the social function of art in the most exciting group exhibit mounted in recent memory, jettisoning overwrought self-seriousness and artistic condescension to embrace honest and fleeting moments of engagement with its audience.

The artists of this exhibition have turned toward America’s collective unconscious—currently gripped by crises beyond the sphere of visual art—to take up the question “what does it mean to make art in America today?” Taken as a single expression, the biennial is a group meditation that considers the essential cultural values responsible for the production and consumption of art, a distillation made possible by the climate of social catastrophe. The photographer Tam Tran, a 2010 participant, is quoted in the catalog as working by aiming her camera at “everything and anything my eyes see and love,” and it is this same exuberant spirit of wanting to feel moved by the things of the world and moved to share those experiences with others that informs the basic purposes of art as a social mode of entertainment.

In challenging the barriers between art and entertainment in popular thought, the most important gestures here have aimed to redraw the boundaries of where one looks for meaning in art to encompass the audience. This is not achieved by way of inclusion, as with Allan Kaprow’s famous 1960s Happenings, which sought to promote an expansive, life-as-art philosophy by moving mundane actions and actors into an art space under the auspices of “performance.” Rather, these artists aim to highlight the characteristics of artworks that draw audiences to them and use them to construct small, momentary experiences that present themselves as welcoming and perhaps playful asides to the rough materialism of life-on-hard-times. In a particularly surprising departure from recent trends in American art, the beautiful is embraced throughout the exhibition as a universally appealing mode of entertainment that has been fundamental to the entire history of art-making, producing a Whitney Biennial that espouses a genuine aesthetics.

Charles Ray’s untitled ink-on-paper drawings, hard-edge renderings of flowers, stand out among such works as breathtaking kernels of composition and novel explorations of the emotive properties of color. They are unspeakably beautiful, and seem—like flowers—to have been created simply so that the world might be filled with beautiful things (though, unlike flowers, this appearance is not at all misleading). The works borrow from the flattened languages of graphic design and Piet Mondrian, while suggesting the close-in detailing of an austere china pattern or an element of exquisite home decor. This endows their visual presentation with a familiar and comfortable sentimentality, as well as an aura of expertise and balanced, understated perfection that upends any notions of kitsch.

Cast on cream paper, the strong, solid hues give the field a warm, plastic tactility that feels implicitly friendly. The drawings are almost aware of their own sensuality, and a moment’s breath before them is sufficient to convince us that Ray wants us to like what we see. The works encourage comfort with their visual and emotional ebb, appealing to the viewer’s notions of beauty that belong as much to the draw of the natural world as to the satisfactions of nice-looking things.

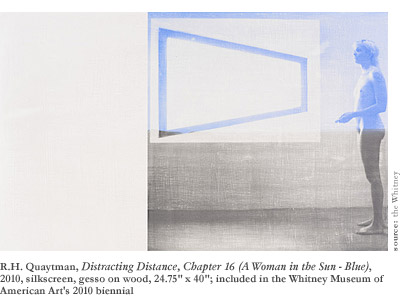

R. H. Quaytman’s series Distracting Distance, Chapter 16, made specifically for the biennial, displays a simple optical phenomenon with a set of strikingly attractive pieces—screenprint and gesso on wood—that play an intimate, inviting game of perception. Each work is a single pattern of repeating lines that stretches the horizontal length and appears black from a distance, if somewhat loosely-grounded. The lines wiggle with the elusiveness of optical illusions and, in a few cases, shimmer with impastoed-on diamond dust. Closer inspection is all but demanded, and it reveals that each apparent line is in fact a collection of three parallel stripes in red, green, and blue—the TV-familiar effect of color saturation meets the viewer’s knowing, delighted smile.

As soon as this small revelation has been absorbed, though, the pronounced, governing geometry of each object asserts itself, and attention quickly boomerangs from the close-up back to the whole piece and the tweaking relationships it shares first with its neighbors and then with the building itself. (Quaytman’s patterns borrow from signature elements of the museum’s architecture, in particular the trapezoidal prisms of its window bays.) Put in simpler terms, these slight planks are fun and appealing to look at, and their discovery stirs the exhibition’s playful aura for its visitors, keeping them floating along with its light pace and snaring them briefly in private epiphanies.

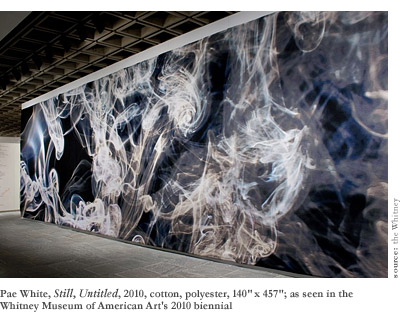

In this way, passing experience is upheld alongside beauty throughout the exhibition as an important source of meaning, tied to notions of both entertainment and escapism. Pae White’s Still, Untitled is perhaps the single most breathtaking work on display in the biennial, and one that embodies its central meditations on the transient, sensual value of art experience. A large, dark work in cotton and polyester that looks mostly like a tapestry, it bears the image of a dispersing white puff of smoke and occupies an entire wall opposite the elevators on the third floor. The work’s size and scale give it a formal grandeur and painterly value that make it a masterpiece, yet it is a quip from the modest catalog essay by co-curators Francesco Bonami and Gary Carrion-Murayari that offers our best clue as to the compelling familiarity that the unique medium carries as a vehicle for beauty and meaning alike: “The domestic and the infinite can often be found in the same place.”

Like a cigarette, a fire, or a hot meal, the viewer’s experience with Still, Untitled furnishes a fleeting escape and a direct, unequivocal pleasure. It is arresting and familiar and a reminder of so many briefly-loved things. This is the promise of the 2010 biennial’s new ephemerality: the passing meaning is not, as in performance, tied to material transience or “being there,” but instead it depends on the momentary refuge an artist can offer her audience. It is the refuge of a cigarette—silent, singular, and necessarily fleeting as a specific experience, yet still a moment in the infinite series of such moments that foster hope, desire, and a will to live in a person’s spirit.

If the great successes of this exhibit lie hidden amid these gestures towards the fleeting, private, and beautiful escapes that sustain sanity in adulthood, its failures share the hallmarks of self-importance and grandiosity. Most of America’s exceptional art since the early 20th Century has depended on a suspension-of-disbelief-like acceptance of its own self-seriousness on the part of its appreciators. One cannot approach the aspirations to sublimity of Jackson Pollock, Richard Serra, or Robert Smithson without conceding some degree of validity to Barnett Newman’s edict, “Any art worthy of its name should address ‘life’, ‘man’, ‘nature’, ‘death’, and ‘tragedy.'” (Newman, by-the-way, makes a stellar cameo as his painting The Promise appears in Collecting Biennials, an exhibition of artworks from past Whitney biennials that are entombed in the museum’s permanent collection.) Here, however, any such pleas fall flat and emotionless.

Curtis Mann’s After the Dust, Second View (Beirut) destroys its own outstanding formal originality with trite, explanation-requiring gestures towards the context of suffering and the source of his images. His process re-treats printed photographs with household chemicals, yielding an arresting visual experience that looks distinct, new, and striking. Presented as works of composition alone, the images seem thoughtful and inventive, but that sense is immediately overshadowed by a lengthy diatribe on their source—a stranger’s Flickr account documenting the thirty-three-day war between Israel and Hezbollah during the summer of 2006.

Supplying this information is a cloying, annoying, and attention-seeking behavior that ultimately distracts from the far more interesting painterly and sculptural values of the work by forcing the viewer to consider the metaphorical implications of chemically altering and destroying the images in the distracting context of a war, rather than the relevant contexts of photography or art-making. Several other artists take up similar tales of suffering as their primary subject matter. In any such instance, the human narratives behind the works are extraordinarily moving, yet when presented as art they invoke less than no emotion, and one stands before them feeling equally resentful of the blatant demands for sympathy and the artists’ hijacking of others’ misfortunes in a display that feels exploitative and exhibitionistic.

The other principal source of disappointment and self-aggrandizement in the biennial is the seemingly ceaseless cavalcade of derivative video art. The medium is strikingly over-represented, a fact made worse by the unimaginative showings from all its practitioners. Greeting visitors just inside the third floor gallery space, the installation Better Dimension by Edgar Cleijne and Ellen Gallagher is an archetypal monument to sadness and failure.

A room-filling wooden box decorated with imagery borrowed from the polemical broadsheets and pamphlets of the American Illusionist Black Herman (famous in the 1920s and early 1930s for his “buried alive” act) and jazz musician Sun Ra, the bulk of the work is guarded by nearly-hidden sliding doors. Inside, video and slide projections alternate between the abstract–painted glass slides that, while unoriginal, are not unbeautiful, and the uninterestingly bizarre. Suffice it to say that the center of the space is occupied by a bust of President John F. Kennedy rotating on an LP. Such work is the epitome of the “Take me seriously!” demands that are ubiquitous in contemporary art, yet in contrast to Newman and others who have made the same cavalier appeal, there is little or no value to glean from cobbled-together, overly deliberate weirdness that revels in its own arbitrariness.

Unsurprisingly, the effect of these works is antipodal to all that is embraced by the biennial at large. They are hostile, diffident, and isolating, shrouded in faux-mystery, and fully propped up by a self-perpetuating cult-of-the-artist. They are uninteresting, unwelcoming, and unbeautiful, dismissing the vital-feeling emphasis this exhibition has placed on the changing role of art in both the private, emotional landscapes of its audience members and the world recovering from ruinous disaster.

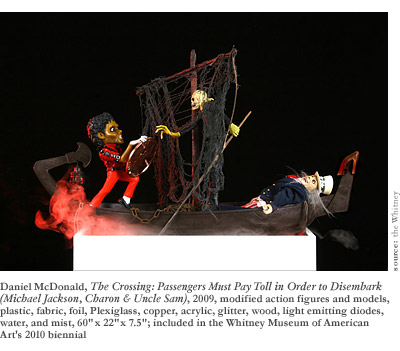

Where it succeeds, the 2010 Whitney Biennial features an art that is fundamentally comfortable being an expression of beauty, entertainment, and the essential value of impermanent experience. Aki Sasamoto’s Strange Attractors wants to be played with as much as Daniel McDonald’s The Crossing: Passengers Must Pay Toll in Order to Disembark (Michael Jackson, Charon & Uncle Sam) wants to be laughed at and Scott Short’s Untitled (White) or Aurel Schmidt’s The Fall want to be thought exquisitely, impossibly beautiful. It is an art that wants to offer alternatives to fear and depression in a moment of collective despondency without brooding over the nature of suffering. If anything, suffering is anathema to the dynamics of the biennial—not disdained, but respected, as the deeply private experiences of unhappiness and strife are left apart by artists who are interested in creating small, momentary distractions from the horrors of contemporary life. In their space, the transcendent value of exposure to beauty, ephemerality, and simple delight coalesces clearly, and what it means to make art in America today becomes what it will take for us to survive, together. This exhibition is one moment along a series of transient, ultimately meaningless moments, but for once it feels as though self-importance is held in reserve, while the artists and their audience escape with a laugh and the passing communion of hope.