In fourth grade, I borrowed from one of my classmates a series of books rumored to be banned from teachers’ reading lists: Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (1981), More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (1984), and Scary Stories 3: More Tales to Chill Your Bones (1991). To this day, I sometimes have trouble eating a meal if I think of this collection of intestine-churning folktales, all researched and retold by the fastidious, mischievous student of folklore, Alvin Schwartz. This is not necessarily due to the content of the stories themselves; in fact, many tales come off playful, with parenthetical directives instructing adventurous storytellers how to scare their listeners. Rather, it is due to my relationship with the searing, viscerally upsetting illustrations in the books, contributed by artist Stephen Gammell. Intended as juvenile entertainment and still considered offensive in some circles, these stories and haunting images have been adapted by director André Øvredal and producer/writer Guillermo del Toro in a collaborative cinematic effort to be released on August 9th.

The Scary Stories film is constructed as a woven compilation of stories culled from Schwartz’s three volumes. It tells of a group of adolescent friends from the fictional town of Mill Valley who trespass on the property of the abandoned Bellows’ family mansion in and around the year 1968. Snooping around, they discover a diary-like tome of “scary” stories penned by the missing/dead Bellows daughter, Sarah. One of these stories, “The Big Toe,” included in Schwartz’s first collection, recalls a small boy who discovers the toe of a corpse while gardening. Awakened, its dead owner then sets out to retrieve the lost appendage. In “The Red Spot,” a young girl urgently observes that the boil on her face is a burgeoning nest of spiders resting just below the surface of her skin. As Schwartz’s stories—“Harold,” “The Dream,” “What Do You Come For?”—are integrated to fit the film’s camp fire-style narrative in one way or another, we feel Øvredal’s and del Toro’s palpable admiration for them (del Toro is on record, profusely, regarding the influence the series has had on him). Rendering many scenes in gruesome detail, they have acutely manifested Gammell’s brutal imagery.

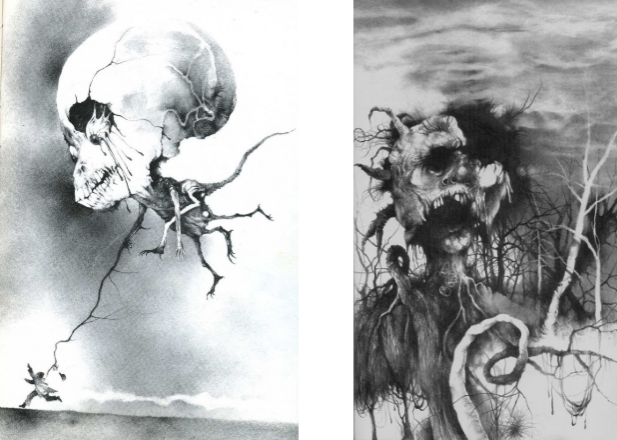

For those who never had the opportunity to process the vaporous illustrations from the Scary Stories trilogy (and for those just initiated), they are a disturbing anchor, enhancing Schwartz’s folktales while disrupting the shoals of eidetic memory. Their existence on the page in chiaroscuro is just enough to burrow into the darker recesses of one’s imagination, like remnants of a bad dream that resist being ignored. Although he had won awards for more endearing and colorful work—including the Caldecott Honor award for his drawings in Song and Dance Man written by Karen Ackerman, and a New York Times “Best Illustrated Books” award for his work in Olaf Baker’s Where the Buffaloes Begin—Gammell made a radical turn with Scary Stories. Some of the images, as in “Sam’s New Pet,” “The Hog,” and “A New Horse,” depict unsettling combinations of animal and human elements, which appear as surreal caricatures.

Others reveal maddening, frequently rural, visualscapes completely tangential to the text. These are enmeshed worlds comprised of decrepit rocking chairs, malformed statues of angels, things borne of tree roots and tendons, and bleeding orbs (or are they small planets?).

It is difficult to surmise just what physiologically occurs in these spaces and with these creatures, for many drawings seem unfinished (dismemberment a common occurrence) and other scenes creep to adjacent pages. An artist who clearly rejects borders and boundaries, both in his career and on the page, Gammell has a fascination with the natural world, its inherent structure, culpability, and mercilessness. The way it’s taken for granted, those common forms we perceive everyday, clearly fuels Gammell’s desire to distort and reconfigure them, into the supernatural and sickeningly uncommon.

It is this preoccupation with the natural world, and specifically Gammell’s pull towards the corporeal—hair, cartilage, dripping orifices—that inspire Øvredal and del Toro in their cinematic Scary Stories adaptation. Gammell’s artwork serves as a gift of raw material informing the film’s storyboards and costume design, dovetailing perfectly with the two filmmakers’ oeuvres. What they have done previously in fostering macabre visualizations that pivot on grotesque expressions of anatomy (the Pale Man from del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth [2006] and the oversized trolls in Øvredal’s Trollhunter [2010], the intimate cinematography and claustrophobic close-ups of Øvredal’s The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016) all come to mind) informs their re-imagining of Gammell’s nightmarish drawings. We catch fractured glimpses of the corpse in search of its toe, its unwieldy skeletal figure disappearing into darkened hallways. The tortured scarecrow Harold, with his insect-infested jowls and rotting frame, buries himself well in our psyche, as permanently as the stake that is his spine. And then there is the Jangly Man, who slips down a chimney, limb after limb, before recomposing himself in a feat of impossibly demonic, anatomical reverie. Traumatizing enough on the page, these ghouls and creatures have now been conjured onscreen to frighten subsequent generations of filmgoers and horror aesthetes.

There were many books that I remember reading in my elementary school days. My favorites were Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, Jerry Spinelli’s Maniac Magee, and Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet, for their short-sentence, narrative-ride brilliance and themes into which I could easily dig my teeth. But Scary Stories remains at the top of the list. They were books kept secret, blasphemous, passed to each other in the hallways. Censored and republished with more palatable illustrations in 2011, this series still rests on bookshelves in the “young readers” section of public libraries, where it will likely outlast those who misunderstood its value to the spirit and imagination of a generation. As for Stephen Gammell, he was my first introduction to the art of horror illustration; I assure you he is the last to have taught me just how impression works.