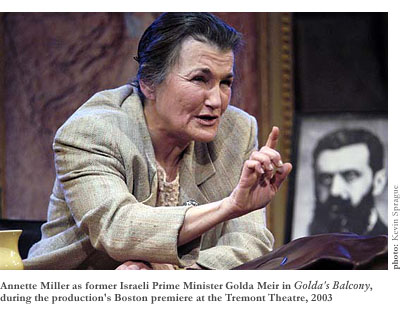

“No wigs, no swollen leg, no false nose,” says Newton-based actress Annette Miller, at the beginning of William Gibson’s Golda’s Balcony, premiering in Boston from January 3rd through February 22nd. Nor is there anything resembling a balcony to be seen on the Tremont Theatre’s low-rise (and consequently rather difficult to see) stage; the set, instead, consists of a bunker-like office, complete with bullet-flecked stone wall, enclosed between sections of a symbolically sliced-up world map. Yet even these visual aids could well have been dispensed with—so convincing is Miller’s transformation into her physical antithesis, Golda Meir (1898-1978), former Israeli Prime Minister, that we would have suspended our disbelief even if she had donned false wings and told her story from a fluffy-pink-clouded heaven.

As it is, Miller depicts Meir as an old woman, reminiscing and reliving the past like a rather hyperactive, slightly deranged grandmother talking to her grandchildren. We watch spellbound as the actress delivers her memory-stretching, ninety-minute monologue without even an intermission, shifting from passionate tears to wry smiles to wistful sighs as she flits among events in Meir’s long life. The balcony in the play’s title actually has two referents in Meir’s story (as Gibson tells it), the disparity between which constitutes a potent symbol of the harrowing gap she discovers between idealism and political reality. The first balcony is that of her idyllic apartment overlooking the Mediterranean Sea—the balcony on which she stands in 1948, feasting her eyes on the newly-created State of Israel stretched out before her. That moment represents the fulfillment of the Zionist dream to which she has devoted herself since declaring her own independence from her parents twenty years earlier. In pursuit of that dream, she has dragged her reluctant husband away from a comfortable life in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and into the austerity of a Jewish kibbutz, returning to the U.S. only to raise money for Jewish self-defense. Admittedly, as an ardent young socialist looking forward to a bright, peaceful future in a world rid of tyrants such as the Kaiser and the Czar, she does not exactly relish her role as an “arms dealer.” Nevertheless, she maintains enough of her idealism to concur with David Ben-Gurion’s assessment that the state of Israel will not only bring to a close two thousand years of Jewish suffering (of which the recent Holocaust was only the finale), but will constitute the very “redemption of the human race.”

A quarter of a century and three wars later, a grim-faced Meir recalls her frequent visits, as Prime Minister, to what her generals called “Golda’s balcony,” which is, in reality, the control room of a secret underground nuclear reactor, built to equip Israel with the atom bomb it considered necessary to guarantee its security against the five sworn enemies that surround it. Unlike the heavenly vista of her first balcony, this one has a “view into hell.” And so we come to the climax, the crisis of the monologue. It is 1973 and Egypt and Syria have unexpectedly invaded Israel and routed its defenses (an event that came to be known as the Yom Kippur War). U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and President Nixon are stalling on their promise to replace Israel’s lost fighter planes and it seems that the very survival of Israel is in jeopardy. Hence, we witness Prime Minister Meir enduring (or, strictly, recalling having endured) a truly dark night of the soul, crying and vomiting through the small hours as she contemplates having to drop atom bombs on Cairo and Damascus in order to deter the invaders from pressing home their advantage. “What happens,” she intones, her idealistic Jewish paradise utterly lost, Armageddon itself beckoning, “when idealism becomes power?” “To save the world you create,” she continues, with Messianic horror, “how many worlds are you willing to destroy?”

Golda’s Balcony, in its current form, actually dates from an earlier version simply called Golda, which William Gibson (most famous for his 1957 play The Miracle Worker about Helen Keller) wrote in the late ’70s, having spent a lot of time in Israel and having met Golda Meir several times. Despite its success, the octogenarian Gibson, now a resident of Lenox, Massachusetts, was unhappy with it and set about revising his script in partnership with nearby theatrical powerhouse Shakespeare & Company. That partnership flowered to the extent that Gibson consented to allow Shakespeare & Company to produce the revised, one-woman version of his play in its intimate Spring Lawn Theatre. And after playing to sold-out audiences for eighty nights last summer, it seemed natural to bring the same production to Boston for its big-city premiere. Shakespeare & Company’s director, Tina Packer, declares herself “proud to be able to present the strength of Bill Gibson’s writing […], proud to be producing Annette Miller in such a powerful piece of acting and Danny Gidron in directing, and proud to be telling the story of a woman who played such a pivotal role in her country’s history.”

Golda’s Balcony, in its current form, actually dates from an earlier version simply called Golda, which William Gibson (most famous for his 1957 play The Miracle Worker about Helen Keller) wrote in the late ’70s, having spent a lot of time in Israel and having met Golda Meir several times. Despite its success, the octogenarian Gibson, now a resident of Lenox, Massachusetts, was unhappy with it and set about revising his script in partnership with nearby theatrical powerhouse Shakespeare & Company. That partnership flowered to the extent that Gibson consented to allow Shakespeare & Company to produce the revised, one-woman version of his play in its intimate Spring Lawn Theatre. And after playing to sold-out audiences for eighty nights last summer, it seemed natural to bring the same production to Boston for its big-city premiere. Shakespeare & Company’s director, Tina Packer, declares herself “proud to be able to present the strength of Bill Gibson’s writing […], proud to be producing Annette Miller in such a powerful piece of acting and Danny Gidron in directing, and proud to be telling the story of a woman who played such a pivotal role in her country’s history.”

Not that the play is a mere homage to Golda Meir. “The dark side” of her single-mindedness, as Gidron calls it, is not glossed over. She describes, without a hint of guilt, her neglect, disregard, and eventual abandonment of her long-suffering husband, Morris. Nor does she express any regret for her subsequent promiscuity around her fellow travelers in the Zionist movement—who, she declares, made her feel alive in a way that Morris never could. Indeed, such self-dramatization, combined with a refusal to admit any fault, recurs again and again throughout the monologue. She always depicts her own motives—as opposed to those of others—as perfectly pure. And she always depicts Israel, with which she feels an almost personal identification, as the innocent victim of hostile or scheming foreign powers. The French, for example, are excoriated for refusing to allow the replacement fighter planes (which Nixon, faced with Meir’s doomsday scenario, eventually agrees to send) to land and refuel on their way to Israel; meanwhile, the significant help that Israel received from France on its nuclear program goes entirely unacknowledged.

Even during that fateful night before the planes are dispatched, Meir focuses not so much on the tragedy of the millions of Arabs who will die if she uses the atom bomb as on the personal tragedy of being the one obliged to take the terrible, conscience-searing decision: of finding herself in entirely the wrong place at the wrong time in history. Indeed, so complete is Meir’s disregard for the welfare of Arabs that she seems frequently to forget their very existence, declaring, at one point, “where nothing was, Israel is”—as if the land west of the Sea of Galilee had not existed before 1948.

Gibson apparently intends us to take such remarks with a pinch of salt. For if the play is not meant to be a homage to Golda Meir, nor is it meant to be an apology for Zionism. Rather, it is intended by the playwright to convey a much more abstract message about, “how good intentions can spill so much blood.” The young Meir voices “the idealism of every major cause in history,” and the dark thoughts that her pursuit of that ideal lead her to entertain are familiar to politicians and revolutionaries the world over.

On the other hand, Gibson certainly does not regret the fact that every word Meir speaks “resonates”—as Miller puts it—with modern audiences used to reading about the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict every day with their morning coffee. This “almost timeless topicality” is, for him, an additional strength of the play. The trouble, it seems to me, is that Meir’s numerous pronouncements on the rights and wrongs of the conflict are liable to entirely consume the attention of a contemporary, politically aware audience—and, thereby, entirely obscure the universal message her example is supposed to illustrate. Gibson himself remarks that “Golda Meir’s story is the story of the State of Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict.” And, given Meir’s articulation of such utterly one-sided assessments as “peace will only be attained in Israel when the Arabs learn to love their children more than they hate the Jews,” it can’t help but come across as Israeli propaganda.

On the other hand, Gibson certainly does not regret the fact that every word Meir speaks “resonates”—as Miller puts it—with modern audiences used to reading about the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict every day with their morning coffee. This “almost timeless topicality” is, for him, an additional strength of the play. The trouble, it seems to me, is that Meir’s numerous pronouncements on the rights and wrongs of the conflict are liable to entirely consume the attention of a contemporary, politically aware audience—and, thereby, entirely obscure the universal message her example is supposed to illustrate. Gibson himself remarks that “Golda Meir’s story is the story of the State of Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict.” And, given Meir’s articulation of such utterly one-sided assessments as “peace will only be attained in Israel when the Arabs learn to love their children more than they hate the Jews,” it can’t help but come across as Israeli propaganda.

Another consequence of mounting this production in such partisan times is that its appeal is bound to be greatest in—if not confined to—supporters of current Israeli policy. It came as no surprise to me that the audience of which I was a part consisted mainly of middle-aged Jewish women mumbling their identification with Meir’s outlook on the conflict. Nor was I greatly surprised to come across this paragraph in a review of the play in the December 2002 issue of The Senior Times: “It’s ironic that as much as we have learned over the years, Jews today still suffer from some of the same ignorance and prejudice that faced them in the ’30s. History has been forgotten. Today’s hate mongers in academia, banning of Israeli goods by some European countries make it so sad and hard to believe that we are living in 2002.” I say again: an audience in 2003 is inevitably going to be more engaged by Meir’s pronouncements on the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict than by any abstract point about the human predicament that her example might illustrate.

Annette Miller (herself a Jewish actress) admitted in a recent Boston Herald interview that some of the things Meir says are “hard to swallow.” “I’m sure some people will see it and say ‘right on,’ and others will say ‘I don’t think you’re giving us the whole picture,’ but I think it’s important to show what goes into a political figure’s decisions. Not just in Israel, but everywhere.” Well, maybe. But even as a neutral, with no connections on either side of the conflict, I found myself yearning for Miller’s monologue to be followed, balanced by a companion piece in which a corresponding Arab statesman told his side of the story—especially given that this is the side that receives the least press in this country.

Hopefully at some time in the future, when the dust is settled in the Holy Land and the territorial arguments are resolved (or at least forgotten), we will be able to view this play from a detached, philosophical perspective and see it as a story about “the price of triumph and the degeneration of ideals” (as director Gidron puts it). However, one can’t help grimly concluding, as the suicide bombers and trigger-happy soldiers continue to conduct their hateful tit-for-tat, that that day will be a long time in coming. For all the undoubted qualities of this production of Golda’s Balcony, I can’t help feeling that, like Golda Meir on that fateful night in 1973, it finds itself in the wrong place at the wrong time.