There’s something satisfying about a group show of visual artworks unified by a single thematic topic, especially when the focus is on an image (such as “house”) and not a concept (such as “home”). Better still when only a few artists are represented in the show—four, say, one artist taking care of each cardinal point on the compass. Let each one be given a chance to display a variety of approaches to the topic, breathing full breath into the body of the work with a skillful, disciplined transformation of the artist’s restless urges and power surges. And let the result, for the art-hungry gallery-goer, resemble the wholesome and appetizing pleasure of having a multi-course meal instead of just one dish. Assign groups of well-sponsored artists such archetypal topics, even, and see what they come up with.

That probably isn’t what happened at the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College. While the crowds were flocking to the cathedral-crazed campus to see paintings by Caravaggio (two years ago) and Munch (this past spring) the McMullen curator, in the mood for something contemporary and novel, probably just noticed that a few interesting visual artists, drawn to the loaded symbolism growing organically from the minute particulars of shelters, had found inspiration in residential architecture recently. Hence House: Charged Space, showing on the college’s Newton campus until September 16, featuring a generous sampling of photographs by Shellburne Thurber, a few paintings by Mark Wethli, a slew of architectural models by Bruce Monteith, and a small bunch of woodworked sculptures by Fritz Buehner.

With more houses in New England than there are alarmed fences to guard them with, how did it happen that one artist, Thurber, decided that she’d better get out of the Northeast and head down South to go scavenging for images in antebellum mansions that seem to have been abandoned only in relatively recent years by Faulkner’s dysfunctional Compson family from The Sound and the Fury? What made her want to park in front of the old Chesson homestead, for example, one sunny autumn weekend in some backwater Confederate town in Yoknapatawpha County, and walk around the house with her camera until she found an open door to enter or (behind the rhododendrons that appear prominently in at least one photograph) a perfectly paneless window to slip through? It must have been the love of that heart-racing sensation you get in a hushed and haunted house, where you swear someone’s still home as you step over the rubble of plaster, porcupine poop, and moth-eaten curtains ripped from their cheap rods, opening daringly one creepily creaking door on its rusty hinges after another.

After exploring the spoiled enamel mess of the kitchen and the electrifying eeriness of the formerly upholstered and well-appointed parlor (where the headlines about the Depression used to be read), Thurber must have summoned the foolhardy courage, all alone and full-well knowing that a skeleton lurked in every closet, to ascend the mysterious stairs we see giving compositional structure and symbolic suggestive power to some of her pictures. Upstairs is where the ancient inhabitants, practically prehistoric, used to rest their soft and vulnerable flesh. She might have let herself be consumed by her love of that profound sense of felt absences gotten from intimate perusal of a stranger’s private space. In her rapture, she took that picture of the corner of the stately old bedroom, its grand hearth blocked now by a stove shield, the shreds and patches of three generations of wallpaper (including a green and red holly-sprig pattern) by chance arranged in colorfully chaotic collage where the plaster has managed not to fall away from the horizontal slats that in other large swaths of the wall give composition and gravity to the crazy mess.

Salvaging the ephemeral and accidentally picturesque moment of decay that is actually taking forever to finish, Thurber must have been acting partly out of love for the people who lived and breathed and suffered there, “muling and puking” as babes and going right on through Shakespeare’s six additional stages of human development until they had to be carried out by their tragicomical Faulkneresque loved ones to the black wagon in the dusty road. Thurber might have meant to evoke—it’s harder to speak for intent than effect—mysterious feelings of pathos by presenting that neat little stack of boxes there in the corner, now so soggy that the cardboard sides have collapsed like flesh falling from bones and the cryptic contents (cloth, newsprint, stationery) have avalanched to the floor.

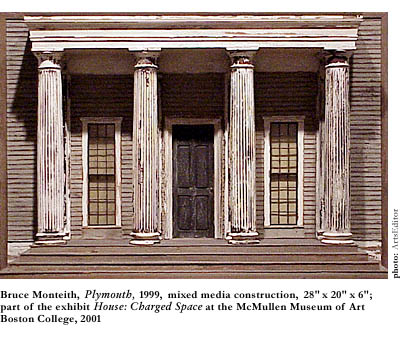

Isn’t it also love of another sort—a kind of humanity-hugging agape for the archetypal resonance stirred by the very façade of a house—that leaves the mouth agape on beholding the miniature models of assorted houses that Bruce Monteith constructed in his woodshop? Didn’t he do well, in his infinite and colossal compassion, with his godlike perspective on the pitiful dwellings we build to brave the elements—saltboxes, duplexes, summer camps, and manses—to let us tower over the little mock-architectural models and take humorous note of the affectionately detailed imperfections of used abodes that he has taken exquisite pains to provide; abodes, after all, that the owners always meant to maintain better; abodes that we could crush with one brutish, anti-art blow of the closed fist?

It must be love of a higher sort, as celestial as a satellite and almost as remote, that made Monteith look far and wide, at modest and monstrous shelter alike, and take such high-spirited note of the imperfections of the used abodes, the details of peeled paint on the severe columns of a very rigid and reserved Federalist house in New England as endearing as the rust on the hinges of the twin doors of a duplex summer-shack or down-South slave quarters. He took exquisite pains to provide these details, and in return must have gained enormous satisfaction in the meticulous re-creation of time’s ravages—as if he had wreaked the same kind of relentless and indifferent havoc on the houses as the wind and rain and icestorms and sun. There’s an open-hearted intelligence to admire, again by way of class contrast more than class conflict, in the equally exact depictions of the decrepit front entrance of his grandfather’s imposing Greek-revival house in Virginia and the dumpy little boarded-up cottage. Rife with both cultural association and idiosyncratic identity, the house façades are left alone, in three-dimensional eye-level view on the wall of the gallery, easy to return to and wonder at over and over with what might even be a lump in the throat for the character they contain.

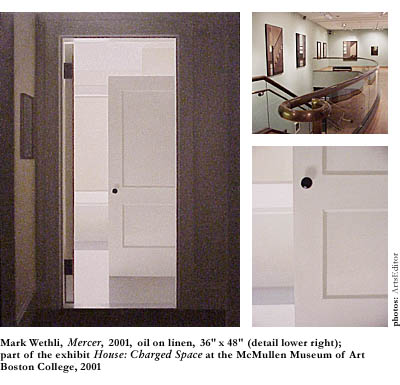

That wouldn’t be the sort of thing you’d say of Mark Wethli’s astonishingly still paintings of the unpeopled, possibly uninhabitable interiors of prosperous-looking New England houses, is it? You wouldn’t say it was love of people, would you, but some purely aesthetic, somewhat ascetic love of light that made him make these paintings, each extremely accomplished large-scale work a study of the way the house receives the daylight that it is offered and proceeds to refract it, categorize it, and both simplify and complicate it, breaking it down into parts and shades and putting it back together again in the form of a residential interior?

You would say that these houses are made as much of light as of wood, and that we can stand before a painting, say, of a bright hallway seen through a darkened door (from inside a space darker than any in the painting) and have a perfectly engaged time counting the shades the single light has been broken down into. We can note the geometrical shapes (of windows, doors, staircases, and furniture pieces) the shadows took on after the light, finding it impossible to put a halt to its downward descent, crashed softly into the house at—yes—the speed of light. Wethli apparently discovered that some shapes are contained partly or wholly by other shapes of light that in turn are contained partly or wholly by others. The perpendiculars, parallels, and diagonals of these illuminating, nearly photorealistic, sheer-Vermeer paintings intersect and overlap neatly and believably. We have to admire how the painter with the world’s steadiest hand never allows us to become completely abstracted by the paintings. We can never forget what objects we’re looking at. We see the details of the house as much as we see the shadows. But we’re not looking closely enough or with enough patience if we don’t find ourselves exploring the interiors and drifting around them with our eyes.

Is Wethli’s a wholly different kind of love from the one that inspired Fritz Buehner to go to the enormous trouble of carving perfect (and perfectly featureless) models of suburban American “homes” out of big beautiful cradle-shapes of cherry wood and maple that still have their bark on them? Is Buehner’s love the love of raw lumber, or is it the love of communication, of reminding us of the raw original source of the lumber that was cut to make the houses during the Baby Boom building boom—in particular, the sardonic, anti-social, nature-loving love of pointing out the absurd contrast between the primal beauty of that wood and the rigid artificiality of “homes” that (at least before they’re lived in) only a realtor could love? Impressive how each ranch house or cluster of ranch houses, attached two-car garages and all, takes its puny place on the vast plain of the varnished split of wood. But we may wonder if Buehner has taken it perhaps a bit too far, carried away by the one strong satirical and surreal idea. We might wonder if it has been entirely worth the expenditure of labor and materials, especially considering the additional absurd contrast—the spun aluminum spools on which he’s mounted the pieces. It seems that his energy could have been better spent on the expression of a higher love than the albeit useful love of satire, especially given the artist’s obvious skill with axes, saws, chisels, t-squares, sandpapers, and varnishes. It’s the love of facile social criticism, the tone of which seems better suited for the comic strips of Matt Groening, when what we might prefer and get more out of is the satiric art with the big heart.

Is Wethli’s a wholly different kind of love from the one that inspired Fritz Buehner to go to the enormous trouble of carving perfect (and perfectly featureless) models of suburban American “homes” out of big beautiful cradle-shapes of cherry wood and maple that still have their bark on them? Is Buehner’s love the love of raw lumber, or is it the love of communication, of reminding us of the raw original source of the lumber that was cut to make the houses during the Baby Boom building boom—in particular, the sardonic, anti-social, nature-loving love of pointing out the absurd contrast between the primal beauty of that wood and the rigid artificiality of “homes” that (at least before they’re lived in) only a realtor could love? Impressive how each ranch house or cluster of ranch houses, attached two-car garages and all, takes its puny place on the vast plain of the varnished split of wood. But we may wonder if Buehner has taken it perhaps a bit too far, carried away by the one strong satirical and surreal idea. We might wonder if it has been entirely worth the expenditure of labor and materials, especially considering the additional absurd contrast—the spun aluminum spools on which he’s mounted the pieces. It seems that his energy could have been better spent on the expression of a higher love than the albeit useful love of satire, especially given the artist’s obvious skill with axes, saws, chisels, t-squares, sandpapers, and varnishes. It’s the love of facile social criticism, the tone of which seems better suited for the comic strips of Matt Groening, when what we might prefer and get more out of is the satiric art with the big heart.

Leaving this remarkable show at the McMullen Museum, we might be thinking of the eye-opening scene in the Faulkner house where the horse gets loose in the house and runs down the hallway with its nostrils flaring; of the sedate suburban house the Cleavers lived in on television in the 60s; of the fortressed castles we’ve seen in northern Italy; of a reoccurring dream that we have entered a shadowy house in the woods by a river, knowing that an ancient woman we’ve never seen waits for us in an upstairs room. We might be thinking of a hundred other shelters that by any other name or dimension—from hogan to mansion—contain the same powerful kind of archetypal quality.

Or, because we’re on the campus of a largely Irish college, we might be thinking of the high-minded poet William Butler Yeats. Even when he lived in a medieval stone tower on the Irish coast, didn’t he long to live more simply on the lake isle of Innisfree, in a hut like that one “of clay and wattles made” that he had read about in the American Thoreau? A house is a “charged space,” like the suggestive title of the exhibit says, because it condenses the wayward energy we bring to it, the way Yeats’ poems did with words that came into them from the outside.