About 50 years after her first hiatus from the art circuits of Huntington Avenue, Reba Stewart (1930-1971) has come back in legacy and in spirit to this community. And now, as it was then, she’s come “like a swirl of energy” to direct and inspire a generation of innovative thought among its students. Her long-time friend Genevieve McMillan, along with the Massachusetts College of Art, has helped bring back to the forefront one of the leading figures of Boston’s own Beat Generation. In celebration of Reba and of the sort of character that she represented during her lifetime, this year will see the inauguration of the Genevieve McMillan–Reba Stewart Traveling Fellowship, to send a graduating senior or recent graduate of MassArt’s Printmaking Department to study abroad. The President’s Gallery is also currently hosting an exhibit of Reba’s work until November 20th. When I asked Ms. McMillan to describe to me her intentions with such a gift, she aligned the spirit of the Beat Generation with that of today’s underground; she used the word “Renaissance.”

I happened to speak with Genevieve McMillan and with Donald Kelley, artist and close mutual friend of hers and Reba’s, on the same day that The New York Times announced the sale of a Willem de Kooning painting for $63.5 million, and a Jasper Johns painting for $80 million. “What would Reba think of these prices?” asked Mr. Kelley, and Ms. McMillan shook her head. This is the commonality between the underground art world then and now, in Mr. Kelley’s perspective; we share a common voice of reaction, each unique to its own moment in history. Then they recalled the vitality of the young generation of artists during the 1950s, crowded into an apartment building on St. Botolph Street behind the New England Conservatory and working odd jobs to support their passion. They joked about the late-night partying and the visits paid by figures such as Dizzy Gillespie. Reba herself was a champion of the disadvantaged, having left her family at the age of 14, and supported herself through the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. “Reba came from nothing,” recalled Ms. McMillan. “No background, no family. And she graduated at the top of her class.”

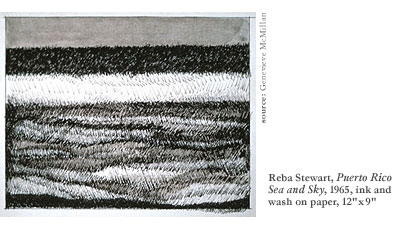

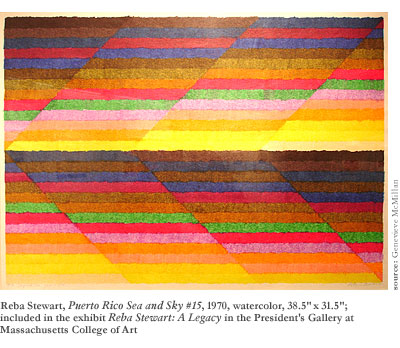

One of Reba’s strongest assets was her curiosity with regard to foreign cultures, and her ambition to pull the far corners of the world into her work. She traveled to Mexico in 1951, ’52, and ’54, where she developed her painting. In 1956 she was awarded the Ruth A. Sturdivant Traveling Fellowship and traveled to Kyoto. There, amidst Japan’s rich history of printmaking, she began experimenting with woodcuts. Years later she would spend a good deal of time in Puerto Rico, absorbing both the local art and the land itself. “That’s where Reba learned to use light,” said Ms. McMillan, nodding to Reba’s Puerto Rico Sea and Sky painting hanging near the window.

The Sea and Sky series makes a strong presence at the President’s Gallery at MassArt, as ink or marker drawings from 1965, and again as larger acrylic paintings from five years later. The earlier pieces seem like landscapes comprised of flattened shape and the steady texture afforded by the markers—abstract and organic. Although the later pieces have a completely different aesthetic from the earlier ones (and to some degree speak of her time spent studying with Josef Albers), both expressions of the series illustrate a unique perspective on the contours of a beach in Puerto Rico.

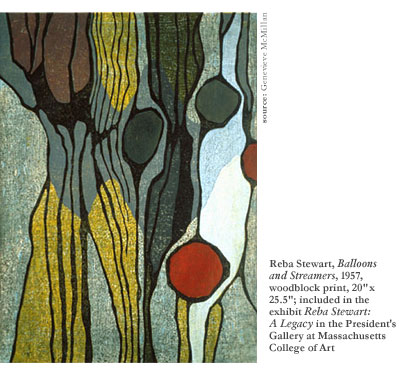

Elsewhere in the gallery is some of Reba Stewart’s earlier artwork, from her time as a student abroad in Japan. There are three pieces from the summer of 1957—Brushwood Thicket, Blue Plant and Vine, and Bull Thistle. These woodcuts, each with a theme of nature underlying the compositions of flattened shape and line, boast a very powerful use of color. They’re broad, abstract forms, enclosed in line like stained glass on paper. She works predominantly in a range of blues and greens, but interspersed throughout is the occasional warm color to offset the vocabulary of “earth tones.” She may have learned to use light in Puerto Rico, but she left Japan knowing color.

The exhibit illustrates one of Reba Stewart’s peculiar qualities, uncommon among established artists: a wide breadth in aesthetic. For students still struggling to find a unique niche that they can explore in a “hit or miss” art world, breadth is a survival mechanism. But established artists often fall into the seductive trap of developing a “trademark style,” and assuming it as their singular dharma—also a survival mechanism. Branding is a necessary element to conducting business, and as Mr. Kelley said, “Artists today are under tremendous pressure.” It’s hard to stray from what sells. Dealers, curators, foundations, and collectors constitute a very exacting force.

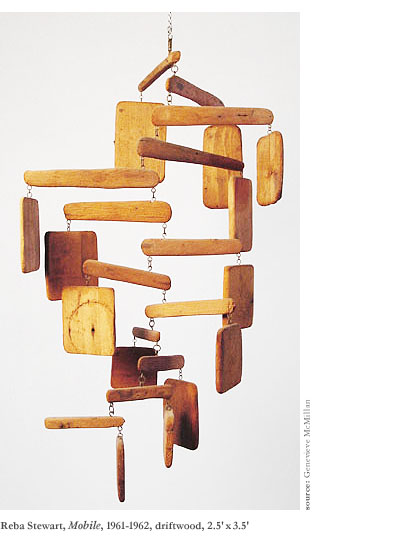

“Reba was constantly developing,” said Ms. McMillan. First the woodcuts, then her acrylic paintings, the marker drawings, the pen and ink, her prints, and an entire expansive series of wooden mobiles, made from driftwood off the beaches of Puerto Rico. They’d once been fragments of coffins, worn away by the saltwater and carried out to sea. And Reba would collect the pieces and send them to her studio in Baltimore, where she’d link them together with hooks and epoxy.

In the memories of those who knew her, Reba was not only an outstanding student and artist, but also a remarkable teacher that believed in close interaction. She seemed to have done her most profound teaching outside the classroom setting, on a personal level. And on more than just technique. “She took people along with her,” said Ms. McMillan. “She adjusted you. Your whole life. Even in her letters.” And she and Mr. Kelley shared a nostalgic nod.

I wasn’t sure whether or not there was a place for that sort of figure in the current university environment. Reba clearly represents a breach in the glass wall of “professionalism” between student and teacher. We talked about the pressure that teachers face today, to stay at arm’s length from their students and keep curriculum before friendship. “Yes, art students today seem better trained,” said Mr. Kelley optimistically. But that did nothing to assuage in any of our minds the difference between a trainer and a true force of influence.

But there is no ideal teacher without an ideal student, and so I was curious for an ideal example. “Could you describe,” I asked Mr. Kelley and Ms. McMillan, “a student that would be perfect for Reba’s style of teaching?” And their response was a succinct one: Ric Haynes.

He was a student of hers at the Maryland Institute College of Art. In his own words: “Her criticisms in class were filled with terror—people would burst into tears, they would slam stuff. There was a lot of hard feeling. She wasn’t easy, and that’s what kids didn’t like—they wanted someone who was easy…I had a problem with the color course that first year, and I got very angry at her because she made fun of me. We had a fight, and I said, ‘You can’t make fun of me—I don’t know how to do this, I’ve never done it before.’ And after class she came and offered to teach me the color course privately, and I went Thursday afternoons 4 to 7, and I started to learn color that way. It was very intuitive—I couldn’t tell you those theories to this day.”

“She exacted many hours of work from them,” added Ms. McMillan. “Her students would have to be very concentrated. Dedicated.” To Reba, a student’s natural ability was not as important as the student’s dedication, and she held them to uncomfortably high standards.

“Let’s talk about the scholarship again,” I said. I wanted to know what role the artist should play in the greater scope of Boston. I wanted to know whether or not that role was being fulfilled now, and how the scholarship would serve that end. Immediately Mr. Kelley shook his head. “Don’t limit yourself to Boston,” he said. “Think globally.” Ms. McMillan said that the scholarship would have a broadening influence, and that artists who have experienced a world outside their own would have that much more to contribute to their environment. But first, “they must get out of the shrunken, provincial world,” she said, in her slight French accent. The artist, in choosing to be an artist, has assumed a great deal of responsibility to his particular time and place, and to strengthen the foundation of his impact, he’ll have to pull from the greatest possible wealth of experience, and forge from it a recognizable voice—unique but laboriously cultivated. And, like Reba, he’ll have to remain flexible and always allow for change.

Talking about the impact of art on the greater scope of society tends to lead to sweeping statements that are optimistic and vague. But as long as we were talking about a single scholarship and a single student, I was curious as to how these lofty ambitions would boil down to the micro level. How could the overwhelming “art and community” question be reduced to the day-to-day actions of a single recipient? “You are always giving back to the community if you’re producing,” said Ms. McMillan, “as long as what you produce is interesting.”

The relationship of the artist to his or her environment is not always a benign one, however, and often beset with antagonism. “The artist’s interests are often way ahead of what the general public is thinking,” remarked Kelley, pointing to Johns and de Kooning in the pages of The New York Times as an example. “Those guys are from our generation.” Much of the art of the ’50s and ’60s was a reaction against the drab, industrializing postwar America, and the need to react was impressed upon an entire generation of artists, musicians, and writers. Throughout the century and before it, some of the most exciting moments in art have emerged from a spirit of outcry. And that spirit has served as an agent of commonality among artists, bringing them together over a similar charge. What does the spirit of outcry look like today? “What have you seen the younger generation react against?” I asked. “And are they reacting together?”

Mr. Kelley again pointed to The New York Times. “It’s just amazing.” He shook his head in disappointment. “It’s all about money. And I think that’s what students are reacting to now.” What would Reba think about these prices? And about the art market? How could you formulate the question to someone who had believed that art and life were inseparable?

Ms. McMillan and Mr. Kelley, with the help of countless others, have assembled a catalogue and brief countenance of Reba Stewart’s life as a student, a teacher, an artist, and as a friend. There’s a chronology of her travel experiences, her influences, and the continual recurrence of turning points that helped shape the figure for whom the scholarship is named. They use the word “reminiscences.” “This scholarship represents the example of a woman,” said Mr. Kelley as we were finishing our visit.

Then, as a final thought, I asked them both how they saw the art student today in light of the voice of reaction that characterized Reba and the Beat community. “Nothing has changed,” said Mr. Kelley. Nothing has changed since Reba’s been away.