“It doesn’t seem right for all of these paintings to languish in a dark vault,” says Ellen Powers, sister-in-law of the late Boston-born painter Marilyn Powers (1925-1976). “They’re such wonderful pictures,” agrees Ellen’s husband Norm Powers—Marilyn’s brother. “Someone should be enjoying them the way we have.”

In the late 1960s, Ellen and Norm took to Marilyn’s paintings so much—she was at the height of her powers then—that they had their Bauhaus home in suburban Boston built more or less around her striking landscapes and sensuous portraits. A lot of those paintings still figure prominently on the white walls of their mod abode. (Past a large painting in the living room, you see through wide windows a snowy copse of oaks on a granite knoll and a steep snowy lawn.) And though the dozen or more Marilyn Powers paintings that decorate their home will go with Ellen and Norm Powers when they move into a smaller place within the year, there are dozens more where these came from.

Thanks to an arrangement with the Judi Rotenberg Gallery on Newbury Street in Boston, approximately 300 paintings will be for sale this winter. “We’re happy to be representing the Marilyn Powers estate,” says gallery director and curator Abigail Ross. “As soon as we can catalogue them and get them safely stored, we will offer the paintings, under a consignment arrangement with the Powers family, to our clients.”

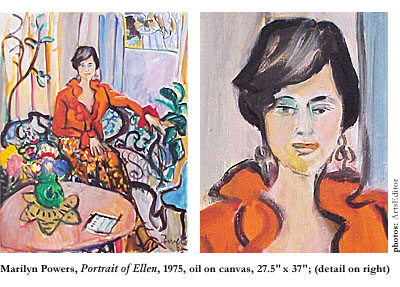

Many of the painter’s signature portraits bear a resemblance—unabashedly, even proudly—to the irrepressibly colorful portraits of Henri Matisse. And though many of them, by virtue of the models’ hair styles, clothing, and surrounding props, are recognizably ’60s and ’70s, they’ve weathered the decades well enough. They’re too abundant in spirit, especially when gathered in a single room, to be period pieces yet. Abigail likens them to the loose and evocative portraits of the late Alice Neel, whose awe-inspiring retrospective played posthumously at the Addison Gallery of American Art last winter. “Marilyn Powers’ portraits tell us a lot about the people,” says Abigail. “They’re more than just accurate depictions of their appearances.” (In reference to her late sister-in-law’s interest in integrating the setting with the figure, Ellen Powers says: “They’re not just portraits; they’re paintings!” And somehow, you know what she means.)

Until Ellen and Norm move, one white living room wall will continue to vibrate with a large, late ’60s portrait of the couple with their three children. It’s one of many luxurious, respectable examples of the figurative expressionism practiced by Powers and her admittedly better-known painter husband of 30 years, Jason Berger. The broad expanses of lilac and cream-colored wall in the painting bring forward the posed figures of the five family members—according to Ellen, uncannily accurate in facial appearance and posture. A few dark brushstrokes sufficed for the architecture of the faces and no more than the essential details of body shape and clothing color. The parents flank their three small children on a couch like the frames of a fan. The family looks to be one piece, as if form and content were one.

When the jolly and hospitable Powers couple sell their house—”It’s time to move to something smaller,” Ellen says of the well-appointed empty nest with the three now-vacant bedrooms their children used to inhabit—they will take the family portrait. They’ll also take, from the wall by the entrance to the kitchen, the opulent 1970-ish portrait of Ellen as a striking woman. Fashionably attired in ruffled orange blouse, long floral skirt, sandals, and dangly earrings, she mesmerizes with her dark-eyed gaze—an exotic and prosperous beauty of her times. Her figure is integrated compositionally, as well as sartorially, into the sitting-room setting. The curves of the loveseat she graces become her, and she becomes them. There’s the sinuous vertical stalk of the tall green rubber plant; the flowing folds of the peach drapes; the vibrant violet wall; and the big smudged blooms of pink, yellow, and blue fresh-cut flowers (hydrangeas maybe) in a green Mexican vase on the coffee table before her. All the details support the aesthetically engaged figure of a person who finds herself, in all senses of the term, in her surroundings.

Of the many dozen portraits on consignment at the Judi Rotenberg Gallery, several stand a great chance of selling for the modest four-figure sum they are rumored to command. The large portrait of the rose-turbaned Indian man named Mr. Dilgir, relaxed and bearded in his brown suit and tie. The one of the prim and literary-looking Jane MacArthur. The sympathetic portrayal of Marilyn’s uncle—Uncle Dick, says Ellen—a lovably ordinary man with just enough dignity granted him by the painter to make it through the day in his red jacket. Joe the housepainter looks good, black brushstrokes comprising the seasoned features of his wizened face. So do the two dangerous portraits of the beautiful dark-haired model reclining on a couch, in what would appear to be Turkish harem pants, almost as frankly sexual with her blouse on in the one as she is with her blouse off in the other. There’s the large close-up of Vivona, a voluptuous, brown-skinned madonna with large supple limbs who is having her luxurious flesh adored by the painter. (To paraphrase T.S. Eliot’s line about roses, these people have the look of people who are being looked at.)

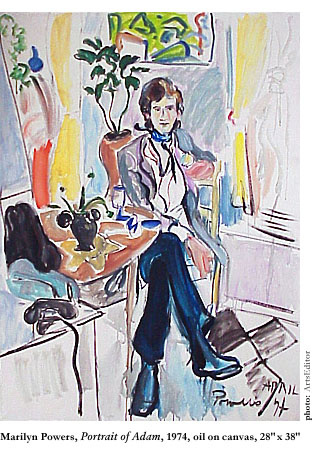

Several portraits of Marilyn and Jason Berger’s son Adam Berger will be up for sale, too. And since the dashing young man himself is probably not available, someone will be likely to take home a portrait of the young man as an artist, maybe the one in which he is looking quite dandy in ascot and long hair and trim suit, his slender legs crossed at the knee, a look of sensuous if gangly indolence on his face. He’s complemented by the colorful kitchen-table surroundings in this painting and by the likewise colorful office surroundings in another. Even the cord of the telephone seems animated. And the window seems “open” in more ways than one. Looking at these loose and dynamic paintings, one can imagine the diligent passion of the painter at work with what Ellen calls her ever-present cigarette. (Marilyn Powers was ever the artist, apparently—blunt and energetic and impatient with niceties; and some have described her as difficult, too.) The portraits of Adam are more than a little in style like that of famous French filmmaker Francois Truffaut, who is depicted reading Ladies’ Home Journal at one of many kitchen tables lucky enough to be portrayed in these paintings. Again, that’s thanks more than a little to the influence of famous French painter Henri Matisse.

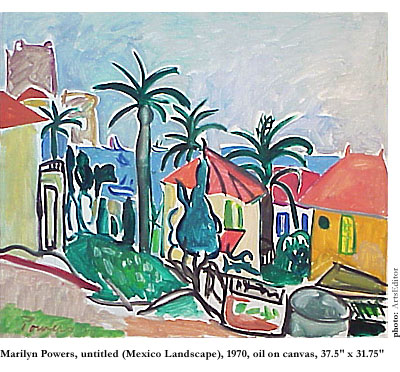

Ellen and Norm will also be taking the two Mexican landscapes from a cozy corner of the atmospheric family room behind the kitchen. Somehow they’ll make room for the 1970 bayscape, painted in the free, plein aire landscape style that Marilyn Powers and Jason Berger emulated in the French Impressionists. Painted from a street up the hill from the deep blue water, the view centers a horizon-line that’s bisected by brown trunks of green-fronded palms, cream and lime-green and yellow green-shuttered stucco two-stories with pitched, terra cotta rooftops, and the belfry of a church. The whole abundant clutter of buildings looks as if it would slide down the hill to the right and on out of the painting if that dependable horizon-line wasn’t there to stabilize the hill.

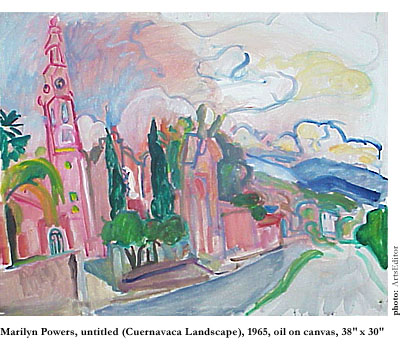

Though a lot of people would like to have it on their family room walls, somehow the Powers couple might make room in their new home for the 1965 Cuernavaca landscape. It’s a dramatic representation of church buildings on a hillside street that disappears in picture-perfect three-point perspective into the lower right corner of the picture plane. Rather than stepping downhill to a shore (and bringing the eye along with them), the buildings in this painting seem to be leaning to their right—the viewer’s left—stretching uphill so not to be sucked into the uncompromising vortex. An exhilarating piece of expressionism, without a person in view to melodramatize the action.

Even though these two Mexican landscapes, as well as several French landscapes from other rooms in the house, won’t be listed for sale in the Judi Rotenberg Gallery’s catalogue, many other landscapes will be. That very loosely squiggled one, for example—as close as Marilyn Powers got to abstraction, perhaps—of the elm tree, or willow maybe, in the park, with the camouflaged forms of water birds (ducks or geese or perhaps even swans) strutting along the bottom of the picture. Or that busy, post-Impressionist piece of verdant village landscape with the zigzag composition of hills and fields helping us to locate the riddingly represented figures of houses, trees, and stooping gardener in the variegated mass of intersecting planes and overlapping squiggles. Or the many other landscapes, too numerous and full of rich details to mention, that would prove Powers, in the outdoors at least, to be the kind of “connoisseur of chaos” that the visually oriented American poet Wallace Stevens admired. Beautifully colored brushstrokes applied with meticulously sloppy effect; no single brushstroke taking precedence over another.

Marilyn Powers was interesting enough as a landscape artist, and clients of the Judi Rotenberg Gallery might be more likely to buy landscapes of places they don’t know than portraits of people they don’t know. But it’s not surprising to learn that in her lifetime Powers was better known for her portraits. Wife and mother, sister-in-law and aunt, daughter and daughter-in-law, she painted multiple versions of her own immediate family, many portraits of her extended family members, and a lot of pictures of people whom her brush made as familiar as family. She appears to have wanted to paint—to familiarize herself with—anyone who had the good fortune to enter her field of vision. And she had a larger sense of family in the art world as well.

When Powers and Jason Berger started the Direct Vision artists’ group in 1971, they did so out of a need for sustained contact with a larger community. They clearly took after the plein aire French Impressionist and post-Impressionist forebears. There are shades of Van Gogh and Cézanne, and always the influence of the Impressionists’ distant descendant Matisse, especially in the way in which the open-aired principles of outdoor painting find their way indoors in the portraits (as if things were wilder indoors than one might have imagined).

The patriarch of the immediate family of Boston-area “figurative expressionist” painters was Karl Zerbe, head of the painting department at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for nearly 20 years. In the late ’40s, when newlyweds Powers and Berger were enrolled at the Museum School, Zerbe had been in the States for several years. He’d brought from Europe the dissonant dark Expressionist tendencies, only to see them passionately embraced, if given a brighter American interpretation, in the paintings of his protégés—among which were several Jewish Bohemian-Bostonians, including Berger and Powers, David Aronson, Reed Kay, and Lawrence Kupferman.

If the Direct Visionaries and their acquaintances formed a second kind of family for Marilyn Powers, then the Judi Rotenberg Gallery is their family room. After all, Lawrence Kupferman’s son, David Kupferman, had a solo exhibition of his abstract “sea light” paintings there this winter. The gallery has represented Marilyn Powers’ widower, Jason Berger, for some time now. Judi Rotenberg herself—mother of Abigail Ross and widow of Richard Ross—is a painter; and her father, Harold Rotenberg, dares to do plein aire landscapes in his mid-’90s. (He had a solo exhibition at the gallery in 2000.)

There’s a good deal of fairly recent Boston art history being preserved and distributed by the Rotenberg Gallery. They’re performing an honorable service for the community, not just running a business.