When she was a young girl, Sarah Lamb remembers that she and her parents “used to play music and kind of run around the living room” in their Jamaica Plain home. “And then my parents decided to put me in ballet class.” At age 6, she enrolled in the Boston Ballet School.

Now 21 and a soloist with the Boston Ballet, Lamb says she is “very happy here” and can’t imagine leaving the Ballet. “I’m keeping my options open,” though, “because ballet is a very ephemeral art form,” she admits. Job security doesn’t really exist, “and we’ve had some turmoil with the directors over the past few years,” Lamb explains.

“I’m very excited for the next season,” she adds, which will include Onegin, one of Lamb’s favorites, and Mark Morris’ Maelstrom, performed by the Boston Ballet for the second time.

Lamb was trained in the Boston Ballet School on scholarship from the age of twelve through graduation from high school. She was immediately accepted into the Company’s apprentice program, and joined the corps de ballet the following year. Now a soloist, she says, “My favorite thing is having a profession doing something I truly love. I doubt that a lot of people are ever able to do what they really love to do as a job.”

Although brought up in the tradition of classical ballet, Lamb has been exposed to Russian character dancing and flamenco. “I did jazz and modern, which was fed to us through the curriculum,” she says, but it wasn’t “real modern, not Graham technique or anything.”

“If you really want to be a professional ballet dancer, you have to spend much more time doing ballet than anything else,” she emphasizes.

Knowing the great importance of proper training, Sarah Lamb is thankful for her mentor, Tatiana Legat, who has coached her since the age of 13. “She is a phenomenal coach and almost a second mother to me,” Lamb explains. “Tatiana is one of the reasons I really want to stay in Boston,” she elaborates, “because she teaches in the School here and I take classes from her and get coaching.”

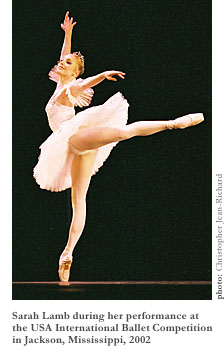

Legat has coached Lamb for every competition she has been to, including this year’s USA International Ballet Competition (IBC) in Jackson, Mississippi, where Lamb took home the silver medal. “A lot of why I do competitions is to be able to work with her,” says Lamb, referring to Legat as “my mentor-idol in the ballet world.”

Sarah Lamb recognizes herself as the recipient of the great legacy of Russian ballet. Tatiana Legat coached Mikhail Baryshnikov and Natalia Makarova, and is the descendent of one of the founding members of the Vaganova method. Also known as the Russian syllabus, “It’s a world-famous teaching method,” Lamb says. “They created the Kirov and the Moscow [Bolshoi] Ballet Companies.”

But Lamb’s admiration does not stop with her coach. “There are lots of other people I look up to,” she says, including several members of the Boston Ballet. “I try to emulate Larissa Ponomarenko,” and the way she deliberately focuses on her hands and arms. “Ballet is not just technique. It’s not just legs and feet, which most people don’t have anyway. But it’s the smaller things, like the port-de-bras and the arms and the hands,” that make the difference between a mediocre performer and a beautiful ballerina. Ponomarenko has taken her upper body expression “and made it transcendent. It’s totally beyond, a step beyond everyone else.”

“And even if you weren’t born with a genetically perfect body, you can take something like a hand, where everyone has the same capabilities, and you can make it speak. You can make it speak in many different ways,” she says.

Making the body speak is the whole idea behind dance, and Lamb recognizes the importance of the individual performer’s interpretation of the movement, a single voice in an elaborate conversation. “It’s a wonderful thing to be able to express yourself and really make yourself a part of an art form.” Her greatest dream is “to do the great roles of different ballets—Giselle, Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, and the list goes on.”

Lamb learned the importance of acting in ballet from former Kirov dancer and Boston Ballet mistress Tatiana Terekhova, who coached her in a number of roles, including Gamzatti in La Bayadère and Myrtha in Giselle.

“Those roles she was famous for, and brought them to another cruel level,” Lamb says, explaining that Gamzatti and Myrtha are the evil women in both ballets. “It was amazing to watch her, her acting and her eyes,” Lamb recalls, adding that the Russians value the tradition of passing on roles to younger dancers with delicacy and respect.

“The Russians are incredibly explicit, incredibly detailed. To them it’s like passing on a diamond ring. It’s a very big deal.”

Myrtha is, in fact, one of Lamb’s favorite roles that she has performed. She laughs, “I look like I’d be the skipping-through-the-fields kind of girl, but I love totally altering my character and assuming a new personality.” Although it is a physically exhausting role with lots of jumping—”almost like a man’s variation, so much jumping”—the real challenge behind Myrtha has nothing to do with the steps.

“She is so mysterious and so relentless,” Lamb says of Myrtha, the leader of the wilis, Bachantae-like women who seize Giselle and kill her lover in one of the most popular romantic ballets. “How much can you get into her brain?” Lamb asks rhetorically, her eyes sparkling with excitement. “What was her story? Why did she get all those wilis together? Why did she become so cruel?”

But ballet is not all about acting, says Lamb. “It’s really a blend of musicality, artistry, and physicality.” And, “It is all about perfection, hitting those exact positions. It makes it more desirable to watch,” she expresses with the opinion that too many American schools “focus on speed and not enough on technique.”

“My belief is that if you train in a Russian class, you’ll learn to hit your positions. Anyone can learn to move faster,” but accuracy is perhaps more important than speed.

Accuracy is put to the test at competitions, like the USA International Ballet Competition, where judges from around the world look mercilessly at young dancers, comparing them to the standard of artistic perfection and not just to each other. Held every four years in Jackson, Mississippi, the 2002 USA IBC took place from June 15th to 30th. An “Olympic style event” in the tradition of sister ballet competitions in Varna, Bulgaria and Moscow, Russia, the USA IBC was founded by Thalia Mara in 1979. That year, seventy dancers from fifteen different countries competed for medals and scholarships.

In 1982, the competition was designated as the official international ballet competition in the United States by a Joint Resolution of the U.S. Congress.

According to Sue Lobrano, the competition’s executive director since 1986, the dancers compete against the abstract ideal of “balletic perfection” rather than against each other. “Unlike the Olympics,” she explains, “the gold doesn’t just go to whoever is the best.”

“The jury has the right to withhold any medal which does not meet the level of artistic achievement” of past USA IBC winners, such as José Carreño, Lobrano says. The highest honor, the Grand Prix, was not awarded this year. “If there is no one dancer of the level to receive [it], the Grand Prix is not given.”

The 13 members of the jury represent former dancers, choreographers, and artistic directors, including Jury Chairman Bruce Marks, former artistic director of the Boston Ballet. Marks has been the Jury Chairman of the USA IBC since Robert Joffrey’s death in 1988, and has served on the jury of competitions in Moscow, Nagoya, and Helsinki. At USA IBC, Bruce Marks is the only American on the panel. In fact, the USA IBC was the first international competition to implement the practice of having one judge per country in the interest of fairness.

The 13 members of the jury represent former dancers, choreographers, and artistic directors, including Jury Chairman Bruce Marks, former artistic director of the Boston Ballet. Marks has been the Jury Chairman of the USA IBC since Robert Joffrey’s death in 1988, and has served on the jury of competitions in Moscow, Nagoya, and Helsinki. At USA IBC, Bruce Marks is the only American on the panel. In fact, the USA IBC was the first international competition to implement the practice of having one judge per country in the interest of fairness.

The application process begins in early February of the competition year and includes both a written and videotaped portion, as well as a written recommendation. It is an honor just to be accepted to compete, Sue Lobrano emphasizes.

98 dancers competed this year, out of a total of 118 who were accepted. “It is very common to lose competitors before the competition actually begins,” she says, but “our goal is to have about a hundred dancers.” This year, the dancers came from 25 countries, including Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Albania for the first time.

The audience is also diverse. Lobrano recalls, “In 1998, we sold tickets to people representing 28 states” as well as other countries. The USA IBC “is truly an international event.”

The competition itself honors innovation, with contemporary choreography required as much as classical variations: segments from such treasured ballets as Giselle, Swan Lake, and Don Quixote.

There are three rounds to the competition, after which participants are eliminated. In the first round, dancers perform a classical variation selected from the competition repertoire. Juniors (ages 15 to 18) and Seniors (ages 19 to 26) select from different classical repertoires, although they share repertoires for the final round. Sarah Lamb decided to do the “Black Swan variation” from Act II of Swan Lake and Giselle‘s Act I variation.

“I love doing Giselle,” she acknowledges. “I love the music [by Adolphe Adam] and everything else about the ballet.”

The second (semifinal) round of the competition requires performances of contemporary works, either ballet or modern, and the third (final) round consists of both contemporary and classical pieces.

For the second round, Lamb used “Sometime, Somewhere,” a solo choreographed by Boston Ballet principal dancer Viktor Plotnikov to music from Bizet’s opera Carmen. In the final round, she did the Act III variation from Sleeping Beauty and “Cello,” a solo choreographed by Gianni Di Marco, another Boston Ballet dancer, set to Bach’s Cello Prelude Suite No. 1.

Speaking of her experience of the competition in general, Lamb says, “It was a very nerve-wracking experience. You’re on a day-to-day schedule and have very little time to rehearse; you spend most of your time waiting and worrying.” Even the performances were not “like regular performances,” she elaborates, because “if you blow your two minutes, you’re going to be either cut or your points are going to go down.”

It is easy to worry “about what can happen,” she admits, making it more difficult to “make yourself perform in a situation like that. In a regular performance, you know someone’s not going to take points off.” When the goal is perfection, mistakes can feel tragic. Sarah Lamb felt “pretty good” about her performances, “which is good for me, because I’m a bit of a perfectionist.”

When the time came for the list of winners to be posted at 2:30 in the morning after the final round, Lamb was too nervous to look for herself. “I didn’t want to be shocked either way,” so her roommate, Boston Ballet corps dancer Brooke Kiser, who didn’t make it to the finals, volunteered. “I still didn’t know what I had won,” Lamb remembers, “so I just showed up in the morning a bundle of nerves, just convincing myself it was the lowest possible prize.”

When the silver medal was announced, “I was pretty impressed,” she says with a subtle smile.

At the end of the competition, the medallists performed in a Gala performance and an Encore Gala. For both, Lamb used the “Black Swan variation” from Round I and Plotnikov’s “Sometime, Somewhere.” Though exhausting, “It was a very good experience, and I was pretty happy.”

Lamb was a finalist at the USA IBC in 1998, and Lobrano was “pleased that she came back and could be successful again.”