Martha Richardson says to make myself at home in the gallery and see if I can sell some of her three dozen Carl Barnas paintings for her while she’s in the back room nibbling at her late-afternoon lunch. It’s a hot Saturday in mid-September and the people coming and going in pairs, fresh from patio lunches and back-to-school shopping sprees on Newbury and Boylston Street, look like they might have the money. With that, she leaves me alone in a chair by the display table out front, where I sit and stare at the paintings of this expatriate German. Barnas left the country when Adolf Hitler cracked down on the independent pursuit of pleasure, but unlike many of his countrymen, he stuck with pastoral Impressionism instead of expressing their dissonance through urban Expressionism. No sooner does the gregarious co-owner of the gallery disappear into the back room, prompting me to draw a notebook from my book bag, than the telephone in her back room rings.

Richardson picks it up, and before I know it, is summarizing the career of this little-known German painter to a familiar colleague in the art world. Fluently reiterating the facts, she recalls with admiration how Barnas refused to join the official Nazi artists’ league, which would dedicate itself to painting pictures of nation-building Teutons who looked nothing like Hitler-comic—book superheroes who got straight A’s in science. “He wasn’t Jewish,” she says into the receiver at one point, “but he had a conscience.” Then she traces the artist’s migration with his family from newly-Nazi Germany—first to Prague, and then to Quito, Ecuador, where an uncle had landed him a teaching position. According to the brochure I’m reading out front, Barnas restored “more than 400 important 17th and 18th Century colonial paintings,” among them some national treasures. Eavesdropping shamelessly, I hear Richardson say that she took to the paintings of Carl Barnas as soon as she was summoned to see them by a dealer. “I sold one picture at the opening,” she exclaims to her colleague, “which is amazing, because I never sell anything at openings.”

Given the focus of Richardson-Clarke Gallery, it’s easy to see why she took to these paintings, which are from the estate of the artist and have been on display since September 12th in the current exhibit Carl Barnas: a Rediscovered Impressionist Painter. From the gallery’s Web site alone, if not from the general look of things in this clean, well-lighted place (Persian rugs, runner lights, and wall-to-wall carpeting), it’s apparent that the gallery sells to a somewhat conservative crowd of aesthetes interested in the restful and representational. Her target audience, well-heeled decorators who could buy the harmless and skillful Boats in the Harbor II, Concarneau, Bretagne, France for its list price of $9,500, isn’t reduced to purchasing $100 gilt-framed reproductions of seashore paintings from home-furnishings stores on Route 9 or $500 originals from weekend watercolorists in Rockport. Nor are they the type who’d be able to front the cash for some newly discovered Van Gogh sketch at Sotheby’s.

Richardson-Clarke Gallery has as many as five Barnas paintings of harvested bundles of grain on sale for a mere $6,000 or so, and they’re not bad either—especially Three Shocks of Wheat, Hessen, Germany. Most of them feature a tall sheaf of wheat like the head of an enormous hearth broom in the foreground, beyond it a receding arrangement of similar shapes in staggered zig-zag patterns or in vanishing one-point-perspective rows that compose the picture conspicuously. Like the Boston-beloved haystack paintings of Monet, the landscapes Barnas painted afforded him the opportunity to apply his palette in a multitude of permutations, depending on the time of day and kind of weather and the corresponding qualities of light and color. If the foreground of the harvest scenes presents a healthy mix of contoured pastures abloom in wildflowers and deciduous windbreaks like those in Monet, the background usually dead-ends the eye (and contains the restless mind) in thick, dark-green woods a mile or less in the distance, under a scudded blue or gray sky. It looks like Hansel and Gretel might emerge from the woods at any moment in lederhosen and dirndl, a basket swinging between them—and in fact the scene of much of the pre-World War I landscape painting Barnas did (the state of Hessen in west-central Germany) is where the Grimm Brothers brooded.

Richardson-Clarke Gallery has as many as five Barnas paintings of harvested bundles of grain on sale for a mere $6,000 or so, and they’re not bad either—especially Three Shocks of Wheat, Hessen, Germany. Most of them feature a tall sheaf of wheat like the head of an enormous hearth broom in the foreground, beyond it a receding arrangement of similar shapes in staggered zig-zag patterns or in vanishing one-point-perspective rows that compose the picture conspicuously. Like the Boston-beloved haystack paintings of Monet, the landscapes Barnas painted afforded him the opportunity to apply his palette in a multitude of permutations, depending on the time of day and kind of weather and the corresponding qualities of light and color. If the foreground of the harvest scenes presents a healthy mix of contoured pastures abloom in wildflowers and deciduous windbreaks like those in Monet, the background usually dead-ends the eye (and contains the restless mind) in thick, dark-green woods a mile or less in the distance, under a scudded blue or gray sky. It looks like Hansel and Gretel might emerge from the woods at any moment in lederhosen and dirndl, a basket swinging between them—and in fact the scene of much of the pre-World War I landscape painting Barnas did (the state of Hessen in west-central Germany) is where the Grimm Brothers brooded.

The diligent, industrious Germans like cleanliness, light, natural bounty, and a little bit of managed wildlife at the edges of their orderly and picturesque lives. Hence the present-day German lead in progressive environmental practices, from fabulous public transportation and resource-management programs to a healthy acceptance of public nudity and the Green Party’s active participation in legislation. The grain in the foreground has been reaped and readied for the thresher; the winding road leading from somewhere beyond the picture plane to our right and down into the gurgling vale toward the middle of the picture has an inevitable look. It’s Impressionism all right, but it’s German, not French, and it’s past the prime-time of the movement, so the painting has a tidy and considerably more articulated look than the Monet classics, say. The painting looks at once more modern and more old-fashioned than the classic Impressionist work—like luminous Hudson River paintings by Thomas Cole or George Inness that someone has toned down and tamed.

Looking between the grain paintings closely, the Monet-mad Boston art-shoppers will find numerous other paintings of German and Dutch landscapes done during the 30 years of work Barnas did in Europe prior to his 1935 departure to Ecuador. On first glance, much of it looks all too familiar—safe stuff you’d expect to see in every other living room of the ritzier Boston suburbs, but never in the gentrified garret of a professorial couple in Cambridge. (Max Beckmann for them, please—German Expressionism as the truer expression of the modern condition.) Yet there’s so much skill and care to be appreciated in the paintings, however conventional the results, that the shoppers are likely to see below the surface of the status symbol an inner beauty that belies the superficial.

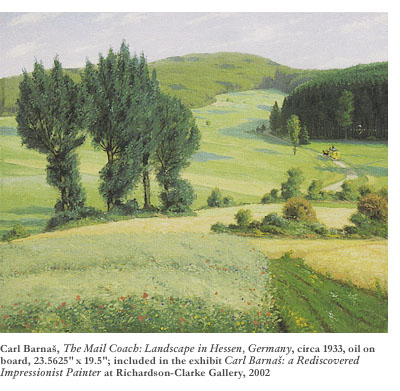

The titles of the modest paintings themselves do not announce the romantic belief, illustrated by the paintings, that in nature can be found the source of inner beauty that has been evoked from the painter, and that all it takes to summon the beauty is some worshipful attention to the landscape painting process. But the titles do invite attention to the detail of the paintings—Spring Rains, Taunus Mountains, Germany; Heather and Pinewoods, Central Holland; The Grain Is Ripe, Central Holland; Der Rote Berg I, Laubach, Hessen, Germany; and The Mail Coach: Landscape in Hessen, Germany, a sweeping summer-valley view with red, yellow, and violet suggestions of flowers in the foreground, the thickly forested hill across the narrow valley, and the fertile patchwork of cultivated fields between the two wild places that a yellow coach drawn by reddish-brown horses is crossing.

The titles of the modest paintings themselves do not announce the romantic belief, illustrated by the paintings, that in nature can be found the source of inner beauty that has been evoked from the painter, and that all it takes to summon the beauty is some worshipful attention to the landscape painting process. But the titles do invite attention to the detail of the paintings—Spring Rains, Taunus Mountains, Germany; Heather and Pinewoods, Central Holland; The Grain Is Ripe, Central Holland; Der Rote Berg I, Laubach, Hessen, Germany; and The Mail Coach: Landscape in Hessen, Germany, a sweeping summer-valley view with red, yellow, and violet suggestions of flowers in the foreground, the thickly forested hill across the narrow valley, and the fertile patchwork of cultivated fields between the two wild places that a yellow coach drawn by reddish-brown horses is crossing.

Finished with her phone call and done with her lunch, Richardson emerges from the back room, warm complexion and relaxed manner a comforting counterpoint to the proper decor. She announces, walking toward a pair of small paintings on a wall, that “these are where this painter really shines.” Squinting from my chair, I see what she means. They’re more private, less grand, subtler, more serene, freer of complicating associations with the usual Impressionist influences that the large paintings in the end might not measure up to. “This one over here I really like,” she says, leading me to a narrow panel of wall near the front entrance. It’s Winter Landscape, Hessen, Germany, and it’s not even a foot wide, but it presents a scene large and inviting enough to walk in—a moody, clouded depiction of a slightly sloped field of dormant bushes (raspberries? blackberries?) in all their twiggy detail, creating a diagonal band of bruise-colored blur that is complemented by a triangular corner of gray-white snow in the foreground and a range of hills in the background, gravely beautified by somber copses of fir trees and a breathtakingly beautiful glimpse of a distant slope of old snow. Under the gray sky, the rolling winter landscape sleeps, and we get to watch it.

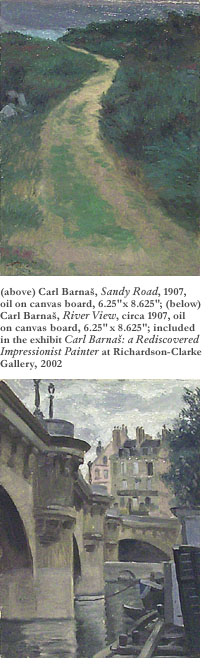

This painting is so obviously a work of love—love of nature, expressed through a brush—that the $4,500 price hardly seems relevant. On panels nearby, paintings of a street corner, a French harbor, and a Dutch willow copse—the latter done in an uncharacteristically brash Expressionist style—serve as more mediocre foils to this fine painting, in much the way the paintings of haystacks serve as foils to the other landscapes. After an hour in Richardson-Clarke Gallery, what prosperous painting-lover would rather look at the kind-of-boring Boats in the Harbor II when the small, portrait-format landscape of Sandy Road, roughly six by nine inches, can more easily evoke the inner beauty of the looker, or at least the beautiful feeling of engagement and enchantment with a work of imaginative art? The solitary walk along the sandy road between bushy pastures can only feel good to the feet, leading us perhaps a bit uphill to a view of a harbor under that light blue patch of sky. We are lucky to get a long view of such an accessible distance, such a foreseeable future.

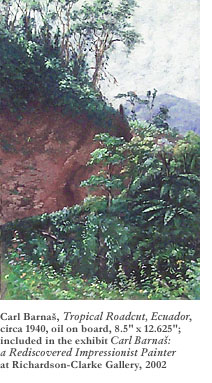

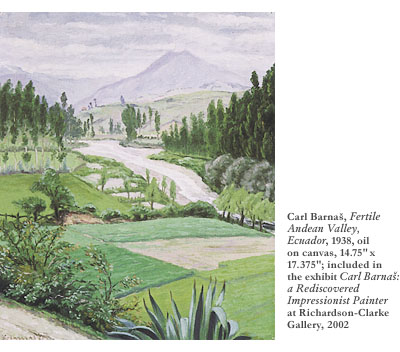

Barnas did continue painting his own works while restoring the antique canvases in Ecuador until his death in his mid-70s in 1953. He worked on a small scale, says Richardson, because canvas was so hard to come by in Ecuador. Five or six of the Ecuadorian paintings are in the exhibit, too, and they could be mistaken for his European landscapes if there weren’t palm trees and maguey cactus plants where the fir trees and berry bushes should be. There seems to be a white volcano (Cotopaxi) in the distance beyond a hillside orchard in one, a greenhouse bursting with tropical flora (orange, blue, and white) by a towering palm in another, and a Fertile Andean Valley, Ecuador in another.

Sometime during my stay, a delivery guy stops by. He’s got a basket of flowers for Martha Richardson. “It’s my boyfriend’s 50th birthday,” she says. “He’s the cook, not me, so I’m doing the flowers.” Little red and yellow roses with tight blooms. Orange poppies. Some light blue, pansy-like blooms and some maroon zinnias (I think). “Hey, I ordered primary colors,” she says. “But I’ll put these on a strong blue tablecloth and they’ll be fine.”