What inspired this eclectic crowd to gather in the C. Walsh Theatre of Suffolk University on such a frigid Thursday night in January? And was the evening worth this effort or would they have been better off curling up in front of the fireplace with a good book and a cup of hot chocolate? The prospect of engaging discussion pulled these members of the Boston arts community together for ninety minutes that evening. Critical Condition, the enigmatic title for this gathering, was dedicated to “addressing issues central to the Boston community of artists.” The discussion was one of the Arts Boston Contemporary Dialogues (ABCD), an ongoing series of lectures and panel discussions. Further, the organizers were ambitious enough to proclaim that this event would be “the first in what is anticipated as an annual series.” If the title seems to hint that the Boston arts community might be in need of the sort of triage normally reserved for Longwood Avenue institutions, the actual topics were less damning. In a single typed page the audience learned that the panel would discuss a broad set of topics via ten pre-determined questions ranging from “What is an art critic?” to the role of the Internet in arts criticism.

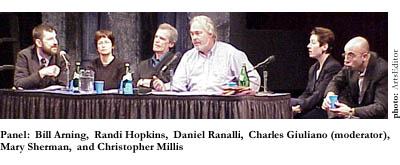

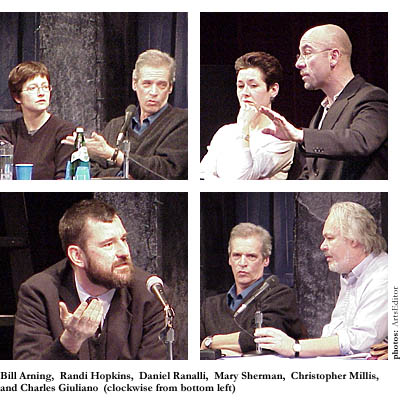

Entering through a portal of silver tinsel, the audience met a dark theatre hosted by notables from the Boston art scene. Charles Giuliano, moderator of the discussion, is the director of exhibitions for The New England School of Art and Design at Suffolk University. Randi Hopkins is co-director of the Allston-Skirt Gallery and a freelance art critic for the Boston Phoenix. Daniel Ranalli is the founding director of Boston University’s Arts Administration program. Bill Arning is curator of the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Christopher Millis is editor of artsMedia and a writer for the Boston Phoenix. And Mary Sherman is a writer for the Boston Herald. They sat above the audience under stage lights and were backed by a set painted like a gaudy Potemkin village. Sadly, like the set behind them, the players on stage provided only brief moments of insight, suffocated by the format for the evening. The setting had all the elements of a powerful experience—engaging hosts, important topics, and a public forum—but these encouraging ingredients were undermined by the organizers’ overly ambitious notions of scheduling and pace. Like a novice painter, a rigid hand frustrated the best of intentions.

In many ways the atmosphere of the theatre permeated the course of the evening, making it difficult for any of the audience members to participate. At several points, under the aegis of expediency, people in the audience were cut short in their responses, as when Michael Price of MPG attempted to explore the nature of criticism versus descriptive writing. Perhaps a better strategy for this evening would have been to focus on one or two questions in depth without the pressure of fitting ten questions into ninety minutes. Also, a town hall format might have served better (versus a stage/audience setup) to encourage dialogue while giving a nod to some of the particularities of New England culture. After all, wasn’t the purpose of the evening to encourage discussion rather than come to any definitive and rapid conclusions?

Moments of illumination appeared over the course of the evening, but more from soliloquy than colloquy, especially in the first suite of questions. One particularly notable exchange came during a comparison of alternative galleries to larger, more conventional spaces and museums. Daniel Ranalli asserted that through their research, his students had found a correlation between advertising dollars and show coverage. (Hmmm, really?). Bill Arning was quick to counter with a contrary argument, citing his New York days when he was a writer who took the time to search for shows of artists that he deemed strong and worth exploring—based on merit, not money. Christopher Millis entered the fray by declaring that the problem of the scarcity of published critiques of alternative space exhibitions is not advertising dollars, but lack of interest on the part of most writers, who would rather focus on blockbuster shows than smaller ones where the readership is likely to be thin. Randi Hopkins added that alternative space galleries actually thrive on their image as “underground,” therefore out of mainstream conventional coverage and review.

The convergence of these points created the most interesting and potentially fruitful of discussions, but in midstream it was cut short. Time’s up. Next question. Turn over your tests and move to Section III. I could hear Charlie Brown’s screams of frustration in the background (“Aaaaaaagh!”). Questions of regional tastes and reactions to them might have been healthy points from which to depart, but were not addressed even though there was the chance to explore the topic with the question: “What is the status of arts writing in Boston? Does what is produced, exhibited, and written about here play out nationally and internationally? If there are local or New England artists—does that mean that there are local or New England writers and critics?”

Another current through the course of the evening centered around the merits of reviews that are purely descriptive as opposed to critical. Strong sentiments surfaced, and most agreed that critique, either positive or negative, was preferable to the white bread descriptive review. Randi Hopkins defended the role of the descriptive review as quasi-publicity for shows, and this point opened up a profound issue at the very heart of arts criticism and the nature of art.

Perhaps the greatest factor in the distaste for the descriptive review is the conflict between artist as “outside commentator” and “established darling of the gallery scene.” There is a certain social expectation of the artist, derived from historical Romantic times, to be removed from the mainstream and wholly focused on the muse that drives the artist to create. Considering this, many have asserted that art is a purely spiritual exercise and can not be valued or commodified. The essence of art is that of eternities experienced on an intimate, subjective level. This importation of spiritual significance adds another layer to the desire for intensive reflection and conversation about works as opposed to a glossing-over for the sake of generating visitors or income. But the line between spiritual significance and economic success is blurred when collectors, like Charles Saatchi, decide to collect and feature artists on the basis of investment opportunity and what might accrue a greater cash value. That is a wholly subjective enterprise in and of itself.

Daniel Ranalli’s point about his students discovering connections between reviews and gallery advertising dollars was the closest the discussion came to the dirty word of the art world—economics. Commercial galleries are businesses first. It is a matter of survival for galleries and critics to feature those events that generate the most public interest and dollars—a supply and demand equation. It is a mystery why economics is never discussed in forums like Critical Condition. Removing it from parlance creates friction between haves and have-nots, and these frictions create rifts at perceived slights, such as the lack of coverage for “alternative events” or too much focus on those artists touted by mainstream galleries. Coverage and its intimate partner, money, were at the heart of the meatier discussions, but for the shortage of time there was a surprising lack of precision in identifying that root.

Overall, the evening included informative points of departure for further exploration, like what a critic is, or where to find alternative spaces in the city. I wish there was more candor behind the explanations of what motivates the decisions that critics make in choosing their subjects. There did not need to be lofty explanations about being paid to pay attention, just truthful answers without affectation. I also came away from the event wondering what could have evolved out of a less ambitious agenda of questions. In an odd homage to serendipity, the discussion and all of its attempts to address grand questions yielded further testimony to that vital core of the creative process—the tension between tapping the eternal and infinite within the brutal constraints of time and circumstance.