A few weeks ago, I rediscovered a book that had been pushed too far back behind others on a set of shelves in my bedroom. Written by James Monaco and published in 1976, it was entitled The New Wave. The pages smelled of spinach steeped in vinegar, and the previous owner’s notes were scribbled in the margins. It seemed a key text for anyone remotely interested in its namesake, the “New Wave” or the “Nouvelle Vague,” a cinematic movement transpiring in France during the late 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Monaco covers the work of five notable directors who contributed to a set of principles outlining a transformation of cinema as they saw it abroad and at home—Jacques Rivette, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, and lastly, Jean-Luc Godard. With their disavowal of a particular cinema that gained hold in France before and immediately after World War II—a “Tradition of Quality” closely modeled after the hegemonic American standards of Hollywood studio production—they sought a compelling change in pursuit of what cinema could potentially achieve as the seventh art.

Among other loosely constructed tenets, the notion of “le caméra-stylo,” a term coined by filmmaker and writer Alexandre Astruc in his 1948 influential essay “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: Le Caméra-Stylo,” circulated amongst the aforementioned directors. This metaphor essentially positioned the camera as an implement to write, much like an author employs his or her pen. Astruc states, “The cinema will gradually break free from the tyranny of what is visual, from the image for its own sake, from the immediate and concrete demands of the narrative, to become a means of writing just as flexible and subtle as written language.” Ultimately, for him, the camera as pen would bring about an accurate expression of thought.

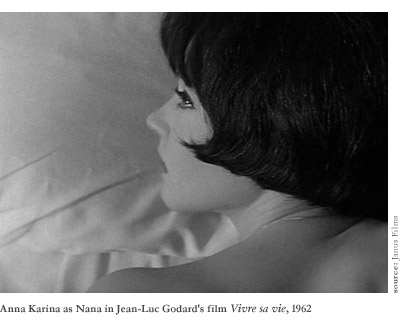

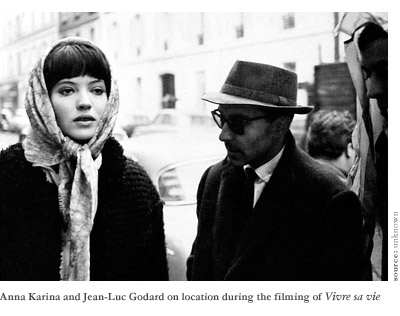

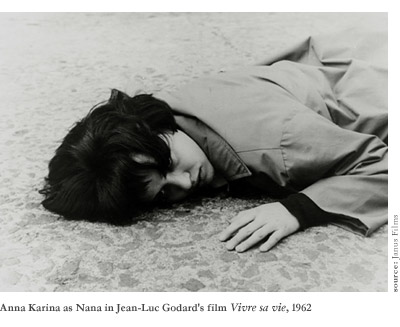

Jean-Luc Godard, in appropriating Astruc’s metaphor, certainly questioned the notion of a cinematic text when he directed the film Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live) in 1962. Based on a work by Marcel Sacotte, it tells its story in twelve “tableaux” or vignettes of Nana, played by Godard’s real love interest Anna Karina, who finds it difficult to make ends meet and ventures into prostitution. The new experiences she encounters turn to boredom, and boredom to death. As this scenario may sound similar to that of an Albert Camus or Jean-Paul Sartre short story, there is a certain departure into existential ennui in the film. Godard even went as far as making this philosophical framework an explicit theme of conversation when Nana advises her friend Yvette that there is “no escape” when we are “responsible for our actions.” But perhaps Godard was never so much concerned with the content of the film as much as the vehicle. Just as Monaco’s book remains a written monument to the New Wave movement, so Godard’s film is a “written” embodiment of its aspirations, some of which can be observed today in contemporary cinematic experimentation.

Vivre sa vie, with its 50th anniversary this year, almost seems a filmic trial, a sophomoric escapade in playing with a new-found medium. It was ultimately a transgression at the time, involving moving images that challenged (and still challenge) virtually every cinematic convention of Hollywood. Godard and his cohorts, who began as critics writing highly polemical pieces for the journal Cahiers du Cinema, founded by the ever-inspiring André Bazin, adored films produced in Hollywood studios. Concerned with genre (especially noir/gangster films and westerns) and character archetypes, Godard respected Hollywood cinema enough to deconstruct its aesthetic ideals. Like any “movement” within the visual arts—Surrealism, Dadaism, and Futurism—concerned with displacing established artistic ideologies, experimentation presupposed the existence of any written manifesto. For Godard, his written manifesto was experimentation with the medium, always under revision in explaining how and to what degree cinema should construct thought for its audience. And he would never shy away from his accountability in producing such thought with the filmic medium: “I still think of myself as a critic, and in a sense I am, more than ever before. Instead of writing criticism, I make a film, but the critical dimension is subsumed. I think of myself as an essayist, producing essays in novel form, or novels in essay form: only instead of writing, I film them.” Although here he seems rather forward in his affirmation of his role as a filmmaker, his films are often anything but. Containing a similar tone anticipated in his first feature, 1960’s À bout de souffle (Breathless), and explored soon afterwards in 1964’s Bande à part (Band of Outsiders), Vivre sa vie is an iconic example of Godard’s kid-in-a-candy-store attitude towards cinema. Although through the twelve vignettes we are capable of grasping Nana’s story, the film still seems an insecure departure into play that speaks confidently of a new self-referential direction in cinematic production.

The “critical dimension” of which Godard speaks is transposed in Vivre sa vie as space and time modified through ellipses, and subsequently, exposition. In a typical Hollywood film, when cuts between scenes follow a logical match with dramatic action and staging—a technique that has gained much leverage internationally—the edits are nearly self-effacing. We watch changes in scenes and tend to pay little attention to transitions because they just “make sense.” Yet in Vivre sa vie, following Bertolt Brecht’s creative methodology known as Verfremdungseffekt (the “estrangement effect”), we find we are coaxed to realize incongruities in the editing of the reality filmed, undoubtedly leaving us to discover perceived incongruities in our own lives. When Godard directs our attention to the film through the juxtaposition of images (no doubt with the help of editor Agnès Guillemot), we are forced to confront the great paradox of cinema: namely, its function in preserving reality while simultaneously exposing it as illusion. Such exposition is relayed in the way Nana glances directly into the camera at a point, as if responding to our voyeuristic gaze. Or perhaps, more implicitly, it is introduced in a quote Nana’s brother Paul casually pulls from one of their father’s student’s poems about a bird: “Remove the outside of a bird, and you will find the insides; remove the insides, and you will find the soul.” With this single quotation, we find Godard manages to use cinema, both in its visual and aural dimensions, as a vessel to cradle thought, even if that thought bitingly exposes the farce upholding cinema’s role in representing reality.

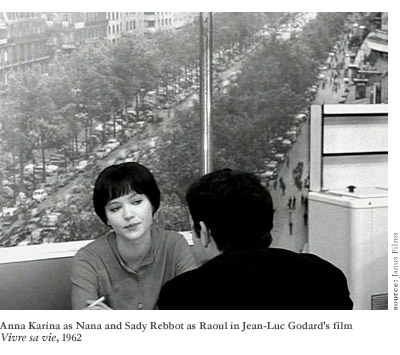

A change in the mechanics of production grants a new perspective. Once again, in provocative reaction to Hollywood’s mode of shaping shots to unobtrusively accommodate dialogue between two characters, a scene is provided that calls attention to its own “scene-ness.” In a moment taking place at a café, when Nana is sitting opposite her new “employer” Raoul (played by Sady Rebbot), the camera tracks to and fro behind him as they converse. Like a pendulum, the camera moves. At certain moments, it ceases its oscillation, leaving us to stare at the back of Raoul’s head, and in turn, obstructing our view of Nana’s body as she speaks to him. Incorporated in this shifting movement is a driving personal statement for Godard—bemoaning traditional technique in filmmaking is creating space which will allow for different interpretations. When we look at this scene and observe behind Nana an enlarged panoramic photograph taken of an obscure avenue in Paris from one particular vantage point, we can only fathom the many visual and theoretical perspectives that this film—and any film—has to offer.

With its purposeful frustration of our expectations, there is room in Vivre sa vie for thinking differently about cinema, more so now than ever before. It stands as an example par excellence of how film could and should affect its audience, and it has wholly anticipated where cinema has gone in the present. From the explosion of experimentation in independent films to the release of the 3D version of Pixar’s Finding Nemo to the “digital revolution” in the image-making industry, a line of latent continuity can be drawn. Visual adornments in a 3D animated movie such as water splashing outwards from a screen in a theatre could be equated with the unexpected aural edits and extension of sound in Vivre sa vie. When the camera depicts a space in which two characters meet and lingers even after they have left the frame, Godard comments on a preoccupation of the most lyrical of cinema today—our modern condition as abandoned and isolated subjects. If he thought of writing films, he did not so much alter the traditional “grammar” of Hollywood films in terms of logical edits and proper narrative architecture, along with other partisans of the New Wave, as much as create a crucial discourse to be argued and modified.

“The cinema cannot but develop,” Astruc stated in his essay. “It is an art that cannot live by looking back over the past and chewing over the nostalgic memories of an age gone by. Already, it is looking to the future…” We celebrate Vivre sa vie as one example of cinema that does just this. In a scene at the beginning, when Nana is working at a record shop, she is distracted by a magazine her coworker is reading. The coworker comments that the piece is boring but well-written, and perhaps out of sheer curiosity to spark Nana’s interest, she begins reciting a passage: “As one who lives intensely, logically you attach too much importance to logic.” It almost reads like a horoscope, or it could simply be a line from a short story. But Jean-Luc Godard was never one for logic in his particular storytelling methods. As she continues to read aloud, the camera pulls away from her and Nana, and begins tracking to the window, where we witness the hustle and bustle of the street—people walking arm-in-arm, conversations cut short due to pressing errands, and chrome-trimmed cars ambling along in traffic. With this particular gesture, as we peer outside and still remain aware of the source of literature narrated, our focus is turned to something else, a thing that is exterior, open-ended. It is Godard’s attempt to animate a historical moment in which cinema was shown to appreciate where it had come from and where it could go.