There is something strikingly similar about sculptor Cynthia Atwood and filmmaker Sanjiban Sellew. As a “couple,” their lithe appearance, wry humor and colorful patterns of speech flow easily in the graceful, eerie way that partners often finish each other’s sentences. It’s an effortless gesture that is not effortless at all.

“It’s not a task that can be checked off even though sometimes you want to approach it that way,” says Atwood. “For both of us it’s a deep vocation. We’re in the process together, yet opposite enough to make it work.”

That vocation is art. And the couple’s commitment to it is as strong as their commitment to each other.

And through art, as well as life, they challenge one another and act as sounding boards for ideas and support during troubling times. “I’d say inspiration is what we feed each other,” says Sellew. Hilarity often ensues. “You never know what’s going to happen. Melting plastic in the toaster oven … soaking something in the tub … cutting the hair off a wig on a bald man in the yard … blow-drying wet rabbit hair … domestic hilarity abounds.”

With an obvious connection to her sewing business, Atwood’s recent sculpture is body-oriented, visceral work that unites feminism, humor, seriousness, sex, eroticism, grotesqueness, beauty, and decay. It also explores historical signifiers as well as contemporary observances.

“The process of making art often involves history and contemporary society and contains things that I contained but didn’t know I contained,” says Atwood, explaining that even though she doesn’t consider herself a feminist, she was unmistakably influenced by the movement as she grew up.

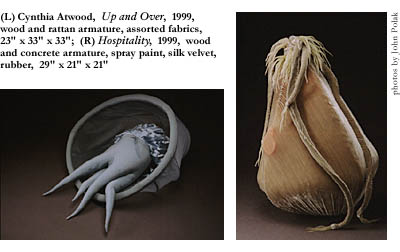

And like her life, Atwood’s work offers similar surprises. Individual, whimsical works of fabric and form vie for attention in the otherwise sparse living room of the couple’s western Massachusetts home. Seemingly innocuous “floaters” of a sheer, pastel green fabric, pinned to the ceiling with thumb tacks, move in small circles overhead. Vinyl and faux fur peek out from underneath. The small toys and wonders at first glance turn into seemingly forbidden views at last blush. Part of the same installation, another challenging yet whimsical piece, Up and Over, appears to change before one’s eyes. A sky blue, pleated skirt is lifted and four tentacled legs splay out. At first it appears as an octopus; a woman’s body emerges as the viewer’s mind imagines the skirt is lifted by the wind or some other swirling motion.

“In all of my work, I walk the line between abstract and literal. The craft of the work is also important. … I want to make many points of entry,” says Atwood.

Gown, a tuber-shaped form made of pink vinyl adorned with the dried skins of fruits, pairs the goofy contours of seemingly incongruous elements with a more sobering issue. Through this type of dichotomy viewers are forced to realize Atwood’s truth about an oxymoron of life: it’s hideous beauty.

“Here is this pink thing that looks like skin but will never decay. And here are the fruit skins that will decay … gorgeous decay,” Atwood says.

Yet despite the “hideousness,” Atwood knows the works, with their whimsical humor and comforting colors, are inviting. One plushy piece weighted at the bottom and curving upward to a slender oval, counterbalanced by oversized buttons, presents the viewer with an irresistible form in its simplicity and graceful symmetry. “A child who was visiting the house saw it and said ‘Dad, lift me up so I can see the tipy top’,” laughs Atwood. Often, her work’s outward appearance is the exact opposite of her original intention. For example, the piece that elicited the awe of the child began as something ugly. She explains: “You’re at a time (in your life) when you’re finding lumpy things that you don’t think should be there; it turns out that it’s okay. … That’s when you edit things on.”

Another unmistakable aspect of Atwood’s work is its unapologetic sexual overtones. In fact, Atwood revels in them. “I am happy that I’ve finally given myself permission to be a completely sexual person. I believe that successful repression is more of what is real culturally that we can’t display … The arts have permission to bring back that information. … That sex is alive and well and sweet.”

A woodworker in his paid profession, sarcastically calling filmmaking an “expensive hobby,” Sanjiban Sellew’s filmmaking career started in what he calls “the film cult” – a production company made up of his cousin Sam Mills and twin brother John Sellew. “I developed stories with Sam, and my brother would do the shooting or act. For fifteen years the Konkapot Big Boys, as their company was known, produced challenging, zany films with artistic bite. “I think that the best work I’ve ever done was with by brother and Sam.

A woodworker in his paid profession, sarcastically calling filmmaking an “expensive hobby,” Sanjiban Sellew’s filmmaking career started in what he calls “the film cult” – a production company made up of his cousin Sam Mills and twin brother John Sellew. “I developed stories with Sam, and my brother would do the shooting or act. For fifteen years the Konkapot Big Boys, as their company was known, produced challenging, zany films with artistic bite. “I think that the best work I’ve ever done was with by brother and Sam.

Although their paths seem to collide artistically sometimes, Sellew has occasionally assisted Atwood in the construction of her pieces and Atwood occasionally makes appearances in his films. In one incident she explains, while he nods in agreement, what is at the heart of their inherent differences.

He had painstakingly helped her construct a perfectly symmetrical armature for a sculpture. “I was very excited and couldn’t sleep, so I had gotten up and gone downstairs. After looking at it again for a while I realized it wouldn’t fit through the door,” says Atwood. Informed of the mistake, Sellew reluctantly shaved the edges – an activity that to a woodworker means “failure.”

“I do things once and that’s the way it’s supposed to be,” says Sellew. “It’s taken me all this time to be accepting of the fact that she doesn’t always have a plan. So here I am wanting a merit badge for this thing and my merit badge is that this thing doesn’t go out the door.”

For Atwood, however, the miscalculation led to opportunity. “I liked it better,” she says. “And, you see, I can’t stand it,” adds Sellew.

Although he’s a tough critic, it’s easy to see that Sellew is hardest on himself when plans go awry.

“Filmmaking – the way I do it – allows me to write, direct, and edit, but I can’t really excel all the way. I don’t think I have that story. You know, that longer story, that movie people will see. … I go to well-crafted movies with Cynthia and I just get lost. I’m always asking her ‘What’s going on?’ I mean, what kind of filmmaker am I?”

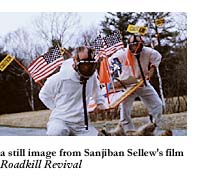

A filmmaker with more than 40 films and 25 awards, that’s what kind. But while the big picture eludes him, the small vignettes – the “beautiful” moments in time – sustain his artistic needs. And independent observers concur.

From his recent work (done independently of the Konkapot Big Boys) entitled A Chicken Will Die, two films – the title film and a two-minute film called I’ve Got Mail – were accepted for inclusion in the Seattle and Mill Valley film festivals.

“I was surprised that they picked it, I didn’t think it was such a big deal,” says Sellew of the two-minute film, which features himself, in a bathrobe, walking to a mailbox that is on fire. Without emotion, his character dons a protective glove, dodges the flames, retrieves the burning mail, puts out the fire and walks back toward a house.

The remarks the piece garnered were highbrow, with critics calling it a “testament to the nature of world news” – its burning issues and constant bombardment. “I thought that was great because it wasn’t about world news at all. The reason I lit that mailbox on fire was that I wanted the best news of the day coming though my mailbox,” he says, explaining the impetus for the film came when his landlord, a volunteer with the local fire department, was paged while performing a housekeeping task. “The beeper went off and then the box squawked for a while and then I heard him laughing. I asked him what was funny and he told me he thought somebody’s mailbox was on fire, and I thought ‘I want that mail’.”

Audiences are the ultimate indicator of Sellew’s artistic barometer and Sellew notices a definite coastal trend. “Locally, A Chicken Will Die didn’t get a big audience,” he says, explaining that while he believes a previous feature-length film may have prejudiced some local film buffs, he is aware that his type of work hasn’t really caught on here in the East. “I feel I had done a substandard job on the 85-minute film so I gave a free showing of this and only 132 people came. A pig roast will bring in 500 people. I think I just had most people scratching their heads,” says Sellew. “So I entered film festivals in L.A., New York, San Francisco, North Hampton, Seattle, and Mill Valley – New York is a ‘no’: shucks; North Hampton, I understand; San Francisco, shucks; L.A., shucks; Seattle and Mill Valley, hap hap happy!”

And while he realizes that the big-name film festivals, such as Cannes, will likely remain beyond his grasp (since his financing has not allowed for the required projectable 16mm film) he exalts in the guerrilla-style format that revels in the life-art similarities and the revealing, life-affirming moments.

“What is most important is that the work is seen,” emphasizes Sellew, who often sends free videos to colleges and libraries around the country to ensure the greatest exposure. “I was once on a woodworking job on Mount Everett hanging a door on one of the cabins, when one of the counselors there, who attended Rutgers, looks and me for a second and then comes up with one of the names from a film … ‘hey, you’re Pinnacle Man.’ … I tell you, that was worth the $2 cost of shipping the tape.”

“And the tape is worth much, much more. After all, I think it’s the only film where you can see a chicken shoot a gun.”