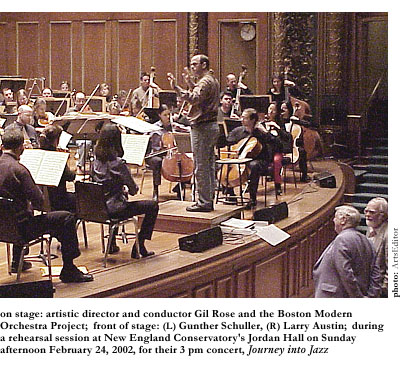

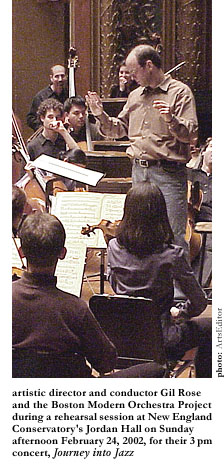

In reading these words, the chances are that you’re parsing distinctly virginal territory. After all, who wants to read an article about modern classical music? Who wants to wade through a series of opaque references to twelve-tone scales, polymeters, aleatory procedures, and the all-around contrapuntal density of various composers you’ve never heard of? Indeed, who would even consider going to a concert of modern classical music if he wasn’t obliged to write an article about it? Not me, I would have answered, as I searched for another topic (to counter this one suggested by my editor). Like most people, I hadn’t been bold enough to venture far into the forbidding classical landscape of the Twentieth Century. How, then, could I possibly conduct an intelligent interview with Gil Rose, the conductor and founding artistic director of the Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP), Boston’s only full-sized, professional orchestra exclusively dedicated to performing works of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Century?

It is surely indisputable that my personal unease reflects a general fear of modern classical music—a feeling that in order to respond to it intelligently one must know one’s musical theory inside out. Not that anyone is similarly put off from listening to pop music, but the widespread perception exists that one must be au fait with all the fiendishly complex machinery of harmony and meter that goes into the composition of a modern classical piece if one is to appreciate it. That is, one must listen not so much with one’s ear or heart as with one’s brain. And the possession of the requisite brain is confined to a few nerdy conservatoire types in black turtlenecks. Right? My only viable strategy, then, was to keep my questions as general as possible, pursuing a discussion of BMOP’s raison d’être rather than its critical preferences or technical expertise. But hopefully my having done so will at least have the advantage of directing a few more eyes beyond this point than might otherwise have been the case.

BMOP’s Web site boldly declares the orchestra’s intention to bridge the “ever-widening gap between the concert-going public and the music of its time”. Hence, when I asked him whether this was not a rather quixotic aim, I expected Rose to reply with an earnest expatiation on how all people could appreciate modern classical music if only they would disregard their prejudice and open their ears. However, he seemed unabashed by the suggestion that modern classical music, such is its esoteric difficulty, is inevitably elitist. He declared himself uninterested in playing the role of “missionary” for the mass appreciation of such challenging composers as Ives, Stravinsky, or Shoenberg. For such appeal, he feels, could only be gained at the expense of dumbing down. To him there is nothing wrong with modern classical music’s appealing only to the “top six or seven percent” of the listening public since, after all, there is plenty of lower grade fare for the other ninety-three percent to consume. Everyone naturally responds to music somewhere near to his or her intellectual ceiling, and it would be a shame if there were nothing to listen to at the more rarefied altitudes but Plato’s music of the spheres.

I must admit that I was impressed by Rose’s refreshing honesty and straightforwardness on this point. It seems to me that there is a lot of what can at best be described as wishful thinking (or, at worst mercenary obfuscation) in the high arts’ insistence on its own relevance to everyone regardless of educational and cultural background. Still, Rose’s statements, in contrast with those of the BMOP Web site, are hardly likely to entice the nervous WGBH listener into a concert of Twentieth Century music, no matter how beautiful Jordan Hall might be. More encouraging, however, is his insistence that the perceived complexity of modern classical pieces in comparison to their predecessors is both overstated and overrated. To his mind there is nothing more musically complex than Beethoven’s late string quartets, yet no one runs for the emergency exits when an ensemble launches into one of those. At the same time, not all modern pieces are complex, and Rose is emphatic in his refusal to acknowledge any link between musical complexity and musical quality (citing Cole Porter as an example of someone whose music is simple yet of the highest quality). Hence, you don’t, after all, need a music degree to appreciate modern musical quality.

But if complexity doesn’t constitute modern musical quality, then what does? That, for Rose, is a bewildering and ultimately unanswerable question (which is why the BMOP logo includes a musical quote from Charles Ives’ 1906 piece, “The Unanswered Question”). For since a “sledgehammer” was taken to traditional schools of harmonic thought in the 1960s, the tree of music has sprouted forth from its unmistakable trunk of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms et al into an almost incomprehensibly vast and complex tangle of ramifications that defy and transcend all attempts at categorization and inter-ranking. Anyone who attempts to make objective judgements about music based on some overarching system of values should be treated as no less of a quack than an astrologer. And, even with the benefit of hindsight, it will take posterity hundreds of years to pick out the rosy pippins from the ever-expanding mass of crab apples currently ripening in composers’ minds.

But if even a conductor gets lost in the dense leaves of the modern musical tree, what hope is there for the rest of us? Well, Rose’s point is partly that no one should feel threatened by any piece of music since no particular style can claim the “high ground” any longer. In other words, it is perfectly valid to simply rely on our gut feelings about which types of music we like; there is no danger of thereby committing any artistic faux pas. Yet, still, how can listeners put what they hear into some kind of meaningful context amidst such a cacophony of competing musical values? This is where BMOP’s “M4” (Making Modern Music Matter) program comes in. Consisting largely of program notes and pre-concert lectures by composers and performers, this “model for audience development” aims to give the audience a “more meaningful listening experience” and to prove that modern classical concerts “can and should be entertaining as well as educational.”

Once again, Rose is unapologetic about the fact that this “fun” can only be had after the hard educational work has been done. For while some people just want a “visceral experience” from a concert, he believes that many enjoy “using their heads.” Not that the M4 project aims to give audiences a crash course in harmonic theory—rather, its aim is to explicate the featured pieces’ historical and social contexts, so that people can “make their own connections” between the music and their own life experiences. Nor are the lectures compulsory or otherwise indispensable. They don’t reveal, for example, the ten things that every listener must know about each piece; to claim to have the keys to such secrets, Rose feels, is just misguided egoism. Rather, they simply point listeners in the right direction if they want to find out more.

Once again, Rose is unapologetic about the fact that this “fun” can only be had after the hard educational work has been done. For while some people just want a “visceral experience” from a concert, he believes that many enjoy “using their heads.” Not that the M4 project aims to give audiences a crash course in harmonic theory—rather, its aim is to explicate the featured pieces’ historical and social contexts, so that people can “make their own connections” between the music and their own life experiences. Nor are the lectures compulsory or otherwise indispensable. They don’t reveal, for example, the ten things that every listener must know about each piece; to claim to have the keys to such secrets, Rose feels, is just misguided egoism. Rather, they simply point listeners in the right direction if they want to find out more.

Rose also enjoys illustrating connections between pieces of music themselves. Hence, his “innovative”, “smorgasbord” approach to programming, which tends to bring together different pieces with certain musical aspects in common. For example, past concert titles have included Pan-Latin Rhythms, Orchestral Music at the Technological Frontier and Cross Currents: Indigenous influences from around the world. Rose admits that such programming risks becoming rather gimmicky, but the equally undesirable alternative, he points out, is to bewilder people with a program of entirely disparate pieces. Ultimately, once again, he feels unable to refute the doubt definitively, describing programming as a “Catch 22 situation.” He always reserves the right to change his mind regarding his orchestra’s direction—which is why the word “project” has been appended to its name ever since its foundation in 1996.

Personally, I felt distinctly inspired by Rose’s wide-eyed, open-minded, there-but-for-the-grace-of-God appreciation of modern music—his modernist preference for questions over answers. Hence, I went to BMOP’s Journey into Jazz concert primed to break out of the popular “saccharine” mindset in which “Rachmaninov strings” constitute the paragon of musical excellence, bristling with contempt for the dinner-suited Mozart-chasers who only attend classical concerts as a symbol of their social status (the real elitists, it might well be argued). Yet my expectations still fell far short of what I actually experienced—which was nothing short of a revelation. True, the pre-concert symposium, conducted by a trio of composers whose works were featured in the program, sometimes went a little over my head (as did the program notes they also contributed). But the music itself went straight to my heart and exhilarated, astounded, and moved me in a way I have rarely experienced before with any era of classical music.

The somewhat kaleidoscopic nature of the music presented was reflected in the frequent changes of personnel and seating arrangements in the orchestra itself. Potentially, one feels that this could have detracted from the quality and coherence of the performances. Yet the musicians—who were semi-casually attired in black, save for the gray-suited jazz quartet who took center stage for the second half of the performance—all performed flawlessly. And much of the credit for that must surely go to Gil Rose himself—the tall, graceful, soothingly assured figure standing amidst the mayhem, his alchemist’s wonder and delight at the transcendent effect of the music’s manifold ingredients very much apparent. The fact that such feelings were also rife amongst the audience was unequivocally attested to by the gasps that accompanied the finales of each of the four pieces performed.

But, alas, the fact that Jordan Hall was less than half full for the performance was also testament to the fact that BMOP still has a long way to go with its M4 project. One can only hope that word of this orchestra’s excellence continues to spread around New England and that they don’t have to wait a whole generation, until the schoolchildren they are currently working with in various outreach programs grow up, before receiving the audiences they deserve. During our interview, Rose quoted the old adage that you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, meaning that no matter what BMOP does to encourage people to attend concerts of modern music, they can’t be forced to engage with what they hear there. However, on this evidence I would say that Rose’s only problem is to lead the horse to the water in the first place. Once there, it will surely drink, drink, and drink some more.