Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) once described her husband Alfred Stieglitz’s character, saying, “It was as if something hot, dark, and destructive was hitched to the highest, brightest star.” This same sense of extraordinary contrast in the artist’s nature is unmistakably demonstrated in his renowned photographic work, perhaps best seen in the distinctive archetypes expressed by his inexorable and life-long documentation of the city of New York.

In 1871, when Stieglitz (1864-1946) was a child, his family moved to 14 East 60th Street, between 5th and Madison Avenues. They were at first surrounded by vacant lots and dirt roads. At the age of 26, Stieglitz returned to America after living in Europe for ten years and found the city transforming into the twentieth-century metropolis that would be forever within his camera’s focus.

Situated in Lower Manhattan at the Seaport Museum New York in the historic seaport district, the exhibition Alfred Stieglitz New York, on view through January 10th, is meticulously curated and well worth a visit. The works are on display for the first time since the artist’s exhibit in 1932—held then at his midtown gallery, An American Place. Guest curator Bonnie Yochelson—former curator of prints and photographs at the Museum of the City of New York—succeeds both through her selection of key works, coupled with a fastidious use of the gallery space.

Entering the first gallery, the viewer is confronted with a vitrine containing Stieglitz’s “portable” Auto Graflex camera (a single lens reflex camera, made for small glass plates or film sheets). This is a slight distraction from the viewer’s introduction to the exhibition, and one that conceivably suggests that the rest will be an intermingled display of images and photographic machinery. Moving into the rest of the room, labeled “Picturesque New York, 1892-1906,” the audience finds the artist’s earliest portraits of the city. In a captivating flourish of pictorial photography’s romance and whimsy, many of Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs taken of New York—particularly in the period following his return from Europe—are emotionally charged and express an air of sentimentality.

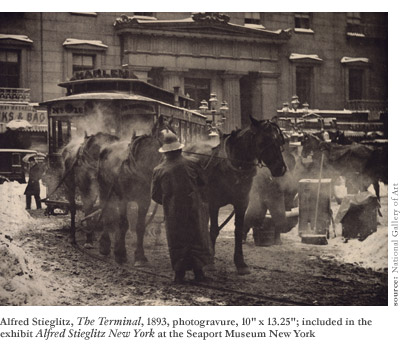

This is exemplified in The Terminal (1893), in which the artist has photographed a driver in his rain coat while he washes down his horses. The steam rises visibly from their bodies. In the exhibit’s accompanying catalogue, published by Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc., curator Yochelson writes: “Upon his return to America, Stieglitz was filled with yearning for what he had left: his freedom, European culture and the picturesque landscape, architecture, and people that had been his photographic subjects.” Later, she tells, the artist recognized this very moment as his earliest re-connection with America, and the first step toward a restored sense of belonging.

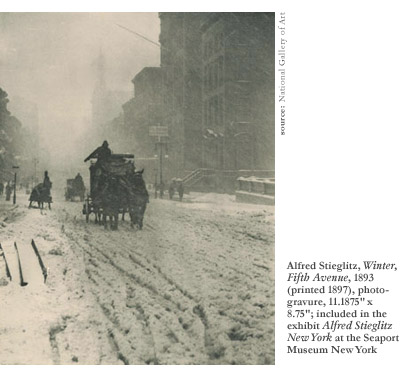

Describing the first gallery, Yochelson cites the images as a demonstration of Stieglitz’s “confidence and originality as a technician and his at times self-conscious uncertainty as an artist.” Stieglitz regularly threw away negatives he was unsatisfied with, and from time to time reprinted from negatives he would rediscover many years after the original was created. Another essential discovery embedded within this first room is Stieglitz’s ability to print more than one version of an image from a single negative—a skill he was certainly aware of, as he exploited it regularly. One particular series of images draws attention—the well-known snowy street scene of a carriage making its way through a storm, titled Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893).

The first version of the three is a photogravure, printed 1897. The carriage is the undeniable focal point, yet fantastic detail is seen in the slush and ice covering the street and sidewalks. The snow almost seems to engulf the city behind the driver and his horses, which appear to be emerging from the storm’s torrential center. The second version, a carbon print from an unknown date after 1897, first contrasts with the photogravure in its coloring. This second, sepia-toned photo offers considerably less detail—apparent in the windows on the buildings lining the street and the relief of the skyline—yet the most significant difference between them is the elimination of the railroad ties found in the first depiction. Yochelson describes this change as somewhat of a conformity made by Stieglitz as a reaction to the Pictorialist movement and a passing interest in darkroom techniques—he had learned to manipulate the surface of the negative, and was eager to wield the new tool. The last image in the series diverges from the other two first by way of its horizontal format, and even more compellingly in the incredible detail revealed as a result of the gelatin silver process. Printed sometime during the 1920s or ’30s, this iteration includes the sidewalks along the road, and is peppered with boys shoveling in the streets. The details reduce the impact of the driver and horses as a singular focal point, opening the image up into a broader street scene.

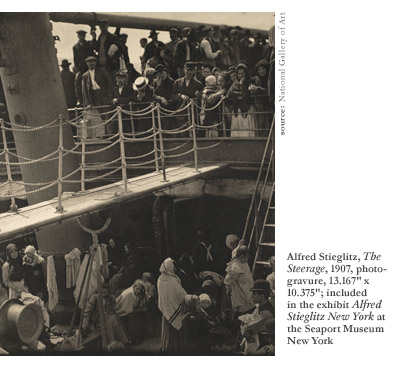

Moving away from earlier works and into the second gallery space, one discovers what are perhaps the most compelling photographs of the exhibition. Titled “Old and New New York, 1907-1917,” this section combines images of water vessels and harbor scenes, including another of Stieglitz’s most famous images, The Steerage (1907). These photographs capture the artist’s move away from Pictorialist representation towards an engagement with modern art. Yochelson describes New York’s growth as a city during that time:

“The 1898 consolidation of the five boroughs, the addition of three more bridges spanning the East River, the opening of the first subway system, and the construction of dozens of ever taller skyscrapers made New York an international symbol of modernity. As he struggled to assimilate modern concepts of representation, Stieglitz retained the modern city as his primary subject.”

Also appearing in this space are two exquisite photographs that demonstrate Alfred Stieglitz’s shift towards modern art, A Dirigible (1910) and The Aeroplane (1910). Devoid of any architecture, these images present the sky as their background with a small hint of earth appearing below in treetops at the bottom of the frames. Visually arresting, A Dirigible presents the airship hovering just above a group of billowing clouds as the sun spills over its hollow sections. The composition invokes a layered effect, forcing the viewer’s eye to travel up through the photograph, finally coming to rest on the dirigible, floating in solitude. Projecting a more abstract and modern tone, the images reflect the deconstructed ideas of representation that characterized the modern period, as well as the artist’s ultimate recognition and embrace of the shift. If strikingly different from many of the other photographs chosen for this exhibition, the works of “Old and New New York, 1907-1917” neither sever the continuity of the exhibit, nor interrupt the visual experience but, rather, they present a lucid distillation of the essential work Stieglitz was creating during a critical time in art history.

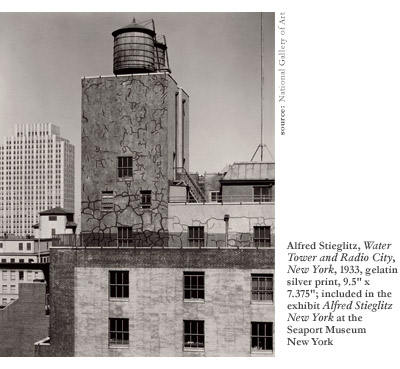

The third segment of the exhibition, “From My Window—New York, 1930-1937,” is the most homogenous, yet its design makes for an undeniably refreshing visual experience. More than half of the photographs hanging were taken by Stieglitz from the windows of the Shelton Hotel where he and O’Keeffe lived from 1925 on. All printed using a gelatin silver process, these images maintain a strong tonal contrast and sharp refinement of detail absent from the previous photogravures and carbon prints. Amusingly, having been shot from both the north and the west (as their titles suggest), the works capture the construction of both the Waldorf Astoria Hotel and the RCA Victor Tower, built just outside his windows.

Taken at various times in the day—and, as Yochelson describes, with various lenses—these images revel in a distinct palette of light, shadow, depth of field, and architectural facets. In a comparison of two north-facing images, the bright, morning light of the first illuminates the outward-facing surfaces of the structures, casting large segments of the buildings in dark shadow, while in the evening photograph, the architectural specter is defined by softer shadows, elucidated by windows emanating manufactured light. In this particular photograph, the city spreads out beyond the focal buildings, appearing as distant, dotted echoes of the central image—a sea of tiny outlets of light that give the viewer a glimpse and a suggestion of the many worlds beyond Stieglitz’s literal view. In another photograph, Water Tower and Radio City, New York (1933), Stieglitz presents a richly detailed view of the neighboring buildings that allows the image to project a sense of physical tangibility. Tiny cracks appear in the surface walls as sunlight falls on a dusty window whose chipped paint gathers on its sill. Individual bricks fill in the cement outline of a second facade of structural design and sun-bleached buttress, drawing the viewer’s gaze even closer to the photograph’s surface. These poetic images, created when Stieglitz was in his later years, invoke his youthful sentimentality through the lenses of age and experience and change, a gesture that stands as the artist’s last great triumph.

By way of an elegantly mapped visual experience, Alfred Stieglitz New York successfully presents a coherent, essential theme through all three sections—a sense of Stieglitz the man, as he saw himself through all the facets of the city of New York. The exhibition is a poignant and compelling display of the photographer’s interrogation of New York City that reflects the singular features of both his lens and his inimitable perspective. Subtly projecting his own emotional life through the images, Stieglitz invites the viewer to share his often isolated world, proving himself one of photography’s most unmistakable and compelling stars, no matter how dark and destructive.