Some artists capture the apex or epitome of a movement—who is more quintessentially impressionistic than Monet? Others find such unique expression that they deftly evade classification, often becoming pigeonholed by impressions of their signature style, as in Mike Kelley’s slacker art. A few individuals somehow manage to transcend their own identity and evolve into cultural entities (Pablo Picasso).

Joseph Cornell is none of these things (or, whimsically, he is all of them at once). The works of his career deftly draw from every major movement of his moment and anticipate some of the most significant developments across 20th Century American art. Born in Nyack, New York in 1903, Cornell’s life began on the eve of modernity’s arrival and assimilation into American art, and his career parallels its assimilation and development throughout the century and up to his 1972 death.

Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination is a brilliant new retrospective of the artist’s full oeuvre whose organization parallels the diversity of his expansive projects, celebrating his foresight alongside his unique achievements. The exhibition opened April 28th and runs through August 19th at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and was curated by Lynda Roscoe Hartigan.

Aptly named, this is an expansive, tour de force exhibition that brings together 180 artworks from every nuanced stage of Cornell’s career, including the public debut of thirty pieces. It sprawls into every corner of the Peabody’s upper floor, filling seven rooms that depict a thematic, rather than chronological, odyssey through the artist’s career.

Guarding the entry foyer to the exhibition’s first section is a towering installation that uses elements from one of Cornell’s book projects, called The Crystal Cage. It is a word collage culled from a work of text and drawings, ensconced within the silhouette of the stone tower inhabited by Bérénice—the Cage‘s central character. The literary piece initially seems like an out-of-place introduction to such a visually structured body of work, yet the rich, suggestive worlds of obsession and fantasy it conjures lurk in the darker corners of Joseph Cornell’s life and work.

“Navigating a Career” is the first of ten sections that constitute the exhibition’s spider web form, also including “Wonderland,” “Cabinets of Curiosity,” “Dream Machines,” “Nature’s Theater,” “Geographies of the Heavens,” “Bouquets of Homage,” “Crystal Cages,” “Chambers of Time,” and “Movie Palace,” showing off several of the exhibition’s prize pieces in the process.

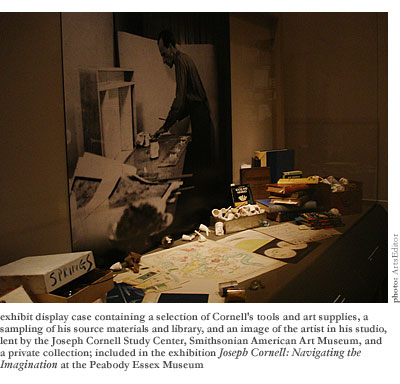

Like all nominative boxes, these categories are largely useless. Except for “Wonderland,” which is not a collection of works but a bric-a-brac recreation of Cornell’s workspace, and “Movie Palace,” which is exactly what it sounds like (Cornell’s works in film), every piece shares thematic material in most if not all of the other sections’ territories.

Despite this first impression, the genius of the exhibition’s design is the ways in which its modular structure echoes the forms of so many of Cornell’s artworks—it feels as though you could only coherently navigate your way through the thematic sprawl with a map drawn by Cornell himself. The museum’s delineations between the spaces (and more importantly between the works each space houses) suggest a means of reading the pieces that intuits their connectedness and encourages visitors to move fluidly among the compartments, tracing meaning across the whole.

Several of Cornell’s most unique and innovative accomplishments fall within “Cabinets of Curiosity,” including Cabinet of Natural History: Object, which the exhibition proclaims is Cornell’s first masterpiece. Comprised of an antique specimen set containing some fifty-odd glass vials filled with colorful minerals, the work assigns each vessel the name of some artist or creator whom Cornell admired, assembling a conglomeration of personalized scientific metaphors that laud his heroes. The work reconstitutes found art along the lines of the artist’s own experience with the discovered treasure, producing a work that is also a model for how to interact with Cornell’s art.

Cornell’s “Bouquets of Homage” form an awkward element of both his collection and the exhibition’s design. These pieces were conceived as gifts for the people Cornell admired, including glorified celebrity figures upon whom he fixated his sterilizing attention. Even though the “Bouquets” presentation offers insight into Cornell’s psychology, the biographical digressions are out of place among works that deserve formal, aesthetic appraisal, often deflecting visitors from experiencing the pieces on their own terms.

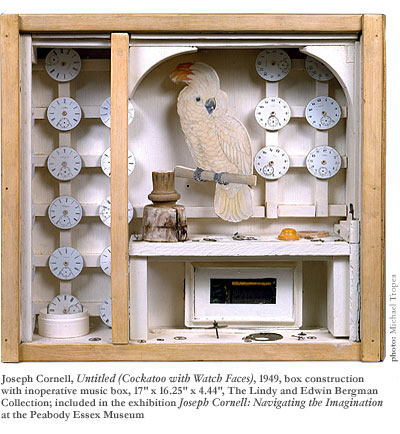

Many of Cornell’s most famous box constructions are clustered together in the “Dream Machines” and “Chambers of Time” sections of the exhibition. Not unrelated, the artist is at his strongest here, earning more than an earmarked place in art history’s soft anonymity. Joseph Cornell almost never left New York City, yet his works transport viewers to worlds far beyond the mundane realities of his urban, terrestrial life. It is in between the spaces of surreal fantasy and the invocation of an infinite, temporal expanse that Cornell truly captures your imagination.

Untitled (Cockatoo with Watch Faces) is a work of staggering brilliance. It is within the juxtaposition of the ephemeral—a simple, white bird of paradise—and the eternal—a wall hung with handless clocks—that Cornell finds an expression all his own. Time, isolation, mortality; these are his realities. Yet he meets them with unbridled dreams and a flight into fantasy worlds. His impressionistic suggestions invoke entire realities in the viewer’s mind through the inflection of the tiniest detail, a child’s trinket.

Hung near this piece is Untitled [Blue Sand Fountain], whose frozen presentation amplifies the surreal sense of infinity, invoking images of a broken hourglass that suspends the imminence of death. Like all of his boxes, it is quiescent and poised, and full of mystery.

The worn aesthetics of antiquity character all of Cornell’s pieces, heightening the sense that these objects belong to another time or culture. They have served some mysterious purposes for eons and will continue to do so—unbeknownst to us—without end.

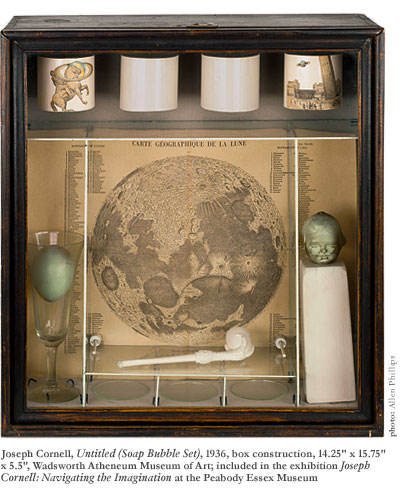

The objects littering the diorama constructions have familiar expressions—the head of that baby doll may have been your sister’s, the bubble pipe your own—yet they remain distant and alienating, as though you stumbled upon a hidden window and, glancing inside, you are confronted by your own subconscious. These are not, in fact, your lost possessions, but shadows of your forgotten dreams.

Untitled (Window Façade) is perhaps the simplest work found in the exhibit, yet the layered, molding grid of miniature frames and painted glass communicates the essence of all of Cornell’s works—it is an artifact of the Other. Artworks like this one hover in the void between painting and sculpture—not quite the minimalist specific objects to come with the 1960s, but they gesture towards new definitions of objecthood while maintaining a genuine dedication to composition. As such, pieces from Untitled (Tilly Losch) to A Parrot for Juan Gris or The Caliph of BagDAD experiment with new material juxtapositions that foreshadow the combined paintings and assemblage works of Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Dubuffet, and Wallace Berman.

Perhaps America’s first consciously postmodern artist, Cornell and his boxes bridge the gaps between Surrealism and later, formalist movements, anticipating so much that has become significant in 20th Century art-making. His earliest critical acclaim (which followed his debut solo exhibition in 1948 at the age of 45) pronounced him America’s leading Surrealist, yet his association with the movement is a peripheral one that mirrors shared interests (the subconscious) more than philosophical or social alignment. Technically, however, Cornell stands alone as an innovator who conceived of unique means to address the formal and subjective problems derived not only from Surrealism, but also Abstract Expressionists, Pop, and Arte Povera.

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) is a lunar relief dreamscape echoed by a child’s disembodied head and an egg suspended in a glass chalice. Four cylinders bearing Renaissance images of cosmic wonder hang in the box’s top tier, augmenting a sense of the adventure and lost history that stretch beyond time and earthbound reality. Beneath it all, a bubble pipe playfully quotes René Magritte’s famous Surrealist painting The Treason of Images.

Cornell intimates an elusive order behind his designs, but denies any obvious, Constructivist link between objects such as the baby and the egg, forcing each individual to find her own set of meanings within the ambiguous, symbolic non-logic of the pieces. Reinvigorating the formal potential of the collage and promoting a materialist appreciation for everyday objects, Cornell derives a new creative language from the sensational, “make it new” maxim of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade. These works are his homage to the modern spirit, and a genesis for Pop, psychedelia, and the postmodern aesthetic.

Beyond Cornell’s successes, the exhibition itself has shortcomings. The space is, through a combination of low-level, indirect lighting and gray walls, uncomfortably dark. While the mood may fit the obscure, brooding sensibility of Cornell’s art, it’s an awful environment for absorbing the details of these small, intricate artworks.

More problematically, the museum has imprisoned Cornell’s works within enormous vitrines. This places the viewer beyond the intimate quarters the pieces demand and totally eliminates any tactile or interactive sense of the objects. The thoughtful addition of stools at many of the displays acknowledges the difficulty of appreciating the works under such conditions, but does not compensate by a long shot.

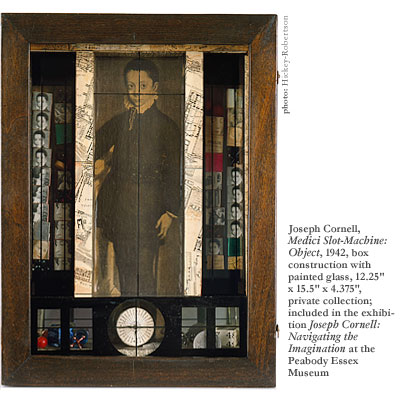

Thankfully, an afterthought video tucked in a corner of the final room offers a compromising solution. The footage, which presents live-action demonstrations of interactive works like Untitled [Blue Sand Fountain] and Medici Slot-Machine: Object as well as semi-transparent overlays of related works, accomplishes several digestive leaps on the visitor’s behalf.

Principally, the video reveals the works as they are meant to be experienced and, even if not allowing the visitor to activate Medici Slot-Machine: Object, opens an imaginative appreciation for its potential. Additionally, the composite images underscore the relationships between the divisive sections of the exhibit, emphasizing the thematic complexity and interrelatedness that unifies the collected artworks.

Several other touches help save the presentation. Cornell’s favorite music (mostly Romantic-era classical) plays in the exhibition’s first chamber (though it would have been equally appropriate throughout), and a stellar piece of interactive software—whose logic is clearly modeled as a cabinet de curiosity nouveaux—can be accessed at several terminals throughout.

If Cornell’s boxes were indeed inspired by Depression-era toys and machines (as the exhibit catalogue claims), then this program is an appropriate transposition, imbedding not only the images and themes of Cornell’s pieces but the ways in which they are accessed within an electronic framework that breathes his wry, playful spirit.

For the first time in over twenty-six years, Joseph Cornell stands alone and his works are as haunting as ever, both in their understated foresight and piercing, subconscious disarmament. The Peabody Essex Museum has assembled a worthy exhibition, navigating the artist’s own imagination and adopting his practices as law to create a new and inspiring experience that immerses its visitors in a truly Cornellian environment.