To appreciate Peter Lipsitt’s sculpture, you don’t have to consider the influence of his mother’s sister, Bashka Paeff (1893-1979)—but it doesn’t hurt. A figurative sculptor who emigrated from Russia as a child before the turn of the 20th Century, Peter’s Aunt Bashka enjoyed the rare privilege of making three-dimensional bronze and marble figures on commission. In the 1920s and 1930s, after an influential art critic spotted her modeling clay forms between sales of tokens in a Boston subway booth, she placed a World War I bronze-relief memorial at a park in Kittery, Maine, a free-standing statue of Warren G. Harding’s pet Airedale at the Smithsonian, and a sculpture of a boy enchanting a bird in a fountain at the Arlington Street entrance to the Boston Public Garden. She also did a bust of the critic who discovered her—a fellow named Philpot—that appeared with the work of other local women artists of bygone days in the exhibit A Studio of Her Own in 2001 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Like her nephew, Bashka practiced a personable style of sculpture. But her unquestionably representative kind of modeling had already gone out of favor in the edgier European and New York studios. The First World War, as cultural lore has it, had broken apart not just bodies, families, buildings, and empires, but comfortable dogmas about art and literature as well, giving way to the Constructivist and Cubist kinds of three-dimensional work that Peter took to with passion in the decade or two before Bashka’s death.

While the Picassos of Paris depicted the world in its brave new state of discord and fragmentation, the Bashkas of Boston continued to provide a more wholesome and hopeful consideration of tragic reality. “She came along in the airstream of other New England sculptors such as Daniel Chester French and Augustus St. Gaudens,” says Peter of her sinewy but smooth realism. Like her predecessors, she concentrated on individual honor and a peaceful sense of closure rather than collective destruction and the clamor that comes with it. Even in the World War I memorial at Kittery, a relief that bears sympathetically gritty resemblance to St. Gaudens’ Boston Common memorial to Colonel Shaw and the African-American infantry he led into fatal Civil War battle, the bodies of the two dead soldiers remain handsomely intact, an unscathed mother and child look over them, and a faithful dog survives.

“I did visit her in her studio, yes,” remembers Peter in response to intrusive questions about Bashka Paeff’s influence on his work. “I was just a kid. She let me apply some bas relief details to the base of a sculpture she was modeling in clay.” (As her nephew would do to save time and energy years later, she farmed out her clay maquettes to foundries that poured them in bronze.) “I imagine her work as a sculptor couldn’t have helped but put a notion in my head.”

Indeed, it must have, because Peter’s life has been shaped since he was young by his interest in three-dimensional art. Before he was out of his 20s, he had studied sculpture as an undergraduate at Brandeis University with Peter Grippe and as a graduate student at Yale University with James Rosati. (He attended Yale during the same general era as sculptor Richard Serra, painter Janet Fish, and others.) Ten years later, back home in Boston, Peter began to share a large studio on the second floor of the Chickering Piano Factory building in the South End. At the time of its construction in 1823, it was the largest piano-manufacturing building in the country, later occupied entirely by artists, and now full of as many families in apartments as artists in studios. Peter has occupied the studio alone for several years now, finding it spacious and resilient enough for the heavy-duty welding of the steel works he’s done all along and for the quieter modeling of wax forms for the bronze casting he’s done for just the past decade. Though he knows his way around a foundry, there is no space in the studio for the casting itself; but there’s room for the considerable amount of work that must be done to bronze castings once they’ve returned from the foundry. “In fact, most of the work begins when it comes back from the foundry,” he notes. “You have to clean it, chase it—a process of cleaning and filing—and apply patina to it.” He does all that light-giving work in a dark industrial atmosphere while the boughs of the white pines in the courtyard (“They were saplings when I moved in,” he recalls) brush the window of his studio, blue jays squawk in the branches, and children who might have modeled for a Bashka Paeff sculpture call out in the playground below—all as if to give Peter’s inanimate metal objects spiritual lives of their own.

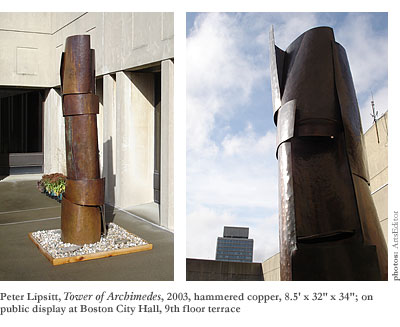

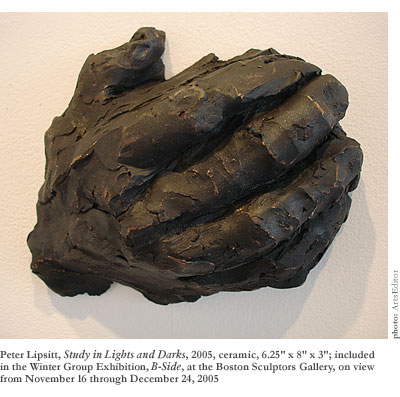

While the intimate early exposure to an accomplished sculptor seems reason enough to remark on Bashka Paeff’s influence, something more subtle has succeeded in finding its way from one generation of family sculptors to another. That would be the sympathetic sense of human consciousness that Peter’s deliberately unfinished-looking forms so inexplicably exude. His sculptures—stacks, screens, and assemblages—never deliver recognizable human forms, and yet by turns they suggest specific parts of the bipedal body (legs and trunks at least), intimate the bony gait, or emulate with scale and texture the benign imposition of a human presence. In the mysterious visual language of abstraction, the sculptures say with withheld words—and with the alchemical patinas Peter applies to them in the studio—that something like a soul is animating the ore.

While the intimate early exposure to an accomplished sculptor seems reason enough to remark on Bashka Paeff’s influence, something more subtle has succeeded in finding its way from one generation of family sculptors to another. That would be the sympathetic sense of human consciousness that Peter’s deliberately unfinished-looking forms so inexplicably exude. His sculptures—stacks, screens, and assemblages—never deliver recognizable human forms, and yet by turns they suggest specific parts of the bipedal body (legs and trunks at least), intimate the bony gait, or emulate with scale and texture the benign imposition of a human presence. In the mysterious visual language of abstraction, the sculptures say with withheld words—and with the alchemical patinas Peter applies to them in the studio—that something like a soul is animating the ore.

To the eye of Aunt Bashka, this soul-sustaining influence in Peter’s unabashedly abstract work may not have been as unrecognizable as her own known abhorrence for modernism would have allowed her to admit. According to Peter, “She kept a scrapbook of clippings from critical tirades against modern art.” And yet one cannot help but think, had she ever visited Peter’s studio the way he’d visited hers, and had she lived to see his work come as far as it has since her death in 1979, that she may have been lulled by a good interpreter into seeing in Peter’s welded steel and poured bronze expressions the presence of a quizzical, bemused, gentle personality looking for a balance of the emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. That his work has been collected by as many museums as hers was by public works administrators—his work belongs to the collections of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, and the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park in Lincoln, Massachusetts—would at least have persuaded her that he’d been keeping up with the times.

If she had lived long enough, she would have been proud to see Peter be a cofounder of the Boston Sculptors Gallery, a frequent contributor to group exhibits in the Boston area, a college-level instructor of art, and a sculptor who has managed to put up a solo exhibition of every phase of his career for three decades. More immediately, Bashka Paeff might have appreciated the 15 or so particular pieces of Peter Lipsitt’s varied repertoire that appeared in his most recent exhibition at the new quarters of the Boston Sculptors Gallery, 486 Harrison Avenue in the South End of Boston.

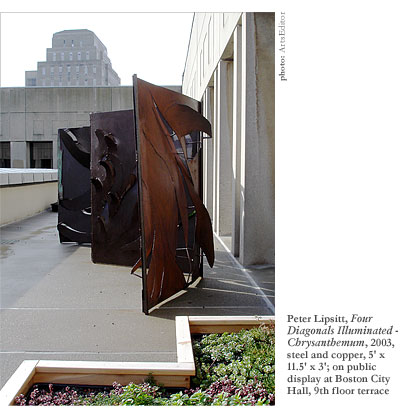

For instance, she might have liked how his freestanding, welded-steel sculpture, Four Diagonals Illuminated, stood there bravely, like a weather-proof dressing-room screen; how its four thick iron walls, joined at alternating 90-degree angles to stabilize it and to give it geometric complexity, got a delicate lift from the several lovely, more or less evenly distributed slits that punctuate its surface, like steam vents in pie crust that a baker cuts with a serrated knife. Given an extra generation of exposure to modernism and Pop Art, she could not have helped but admire how these graceful slits, which now seem like large eyelids more than cuts in pie crust, simultaneously honored the environment and served themselves, generously allowing air to pass through and getting some ventilation in return—providing participants in its environment glimpses through to the other side of the screen and having its elaborate beauty admired by many. As an artist of considerable social conscience herself, Paeff might have concluded that the piece—”Actually, it’s an abstracted Japanese chrysanthemum,” explains Peter, and the slits do, after all, suggest moist petals in a fragrant bouquet, especially from a distance—is not entirely unlike a social creature who makes concessions and compromises for the greater good of itself and its fellows.

As it happens, there’s plenty of evidence in the recent work by Peter Lipsitt that appeared under the collective title of Tangent Links at the Boston Sculptors Gallery, of this essentially kind effort to take pleasure in social interaction. It informs the numerous stacks that Peter has been making for several years now, including one beautiful little stack of irregularly formed but smoothly finished cylinders called Markers. The coiled slabs of bronze stand end to end, one on top of the other, like vertebrae or bracelets. But the two ends of each coiled slab (all with a warm copper patina) don’t quite meet, don’t quite come to a closure about anything. They’re almost there, almost complete and perfect and polished, but not quite. (They’re deliberately, refreshingly, poetically unfinished, just like almost every project a mortal person attempts in this life, bringing to mind Valery’s well-known remark that a work of art is never finished, only abandoned.) In each of the four bronzed-together segments, stacked irregularly less in defiance of symmetry than in reluctant submission to its tyranny, Peter has left a gap that evokes the beauty of a personal imperfection so courageously recognized and admitted and lived with that it has become the subject of the art itself. Together, the irregular stacking and the incomplete coils evoke the intense sweetness of tragic character that Sherwood Anderson insisted could be found not in the perfect specimens but in the twisted apples he found fallen on the ground in the orchard at the edge of town.

For lack of more pretentious jargon, Peter’s works are post-confessional, re-constructivist sculptures. In other stacks, a cylindrical construction not even a foot tall might evoke the image of an architectural column with square base and capitol. In an assemblage, a coppery green cylindrical form twisted like a cruller and complicated by scroll-like forms and a gorgeous little lily pad-like form all diverging and converging in a vortex of evocative debris, might suggest a tornado in a mathematician’s head. In Chart of the Known World, a large wall-hanging of blasted steel, brass, and copper that he displayed at the Boston Sculptors Gallery before it moved its quarters from the Chapel Gallery in Newton, the collage of metal shreds, ribbons, and patches seems to be moving in a hurried group that didn’t have time to pick up after itself but was urged into motion by an irresistible force toward some unusual appointment to the participant’s right.

Turning from the coils to the assemblages, the newly appreciative Bashka Paeff might have wondered what sort of juxtaposition of planes, rods, and cones to expect next, and how Peter managed to get the rough geometric pieces to take their shape at the foundry so poetically. She might have wondered how he’d persuaded the individual pieces to look as though battered collectively by the turbulent weather of some human desire—and why it is that such non-representational juxtapositions can suggest the disparate elements of an identity that a person has spent all of his life patching together, only to see it cool from a molten metamorphic state to a static state he’s stuck with for good. Finally, she might have realized, adding the vocabulary of abstraction to her sensitivity to the figure and her fundamentally principled tenderness toward existence, that her nephew’s sculptures are grand gestures of lightly handled heavy metals on an ironically diminutive scale that is perfect for the gallery pedestal but that would also seem to be suited just fine for a grand plaza in Boston. Not far, say, from her boy and bird in the Public Garden—maybe near the corner of Arlington and Beacon, where a rather kitschy statue to anesthesia and its development as a battleground blessing has stood for several decades now.

If the imperfect specimen who is Peter Lipsitt (presumably different from the conscious social creature who is Peter Lipsitt) were less modest and self-effacing, and if public funding for art were there, many poetic miniatures of the site-specific monuments to spiritual idiosyncracy that appeared in his exhibit at the Boston Sculptors Gallery would find their way to such plazas. But at what cost? And to what necessarily better effect than they achieve in a gallery, where it’s easy to hear their small but stirring soliloquies in steel and bronze, surprising to see the heavy metal choreographies that make light of the industrial materials they consist of? It’s good enough to look down at the miniature monuments to the cumbersomeness and beauty of the body and see that the figure, or the sense of it anyway, survives in abstract sculpture. (“I reference the human form,” he explains, “in the tactile sense of touch, in visual suggestions of rhythm and melody, and in conceptions of spatial line that sculptors share with other visual artists.”) What the mini-monuments have to say can be said to one or two people at a time.

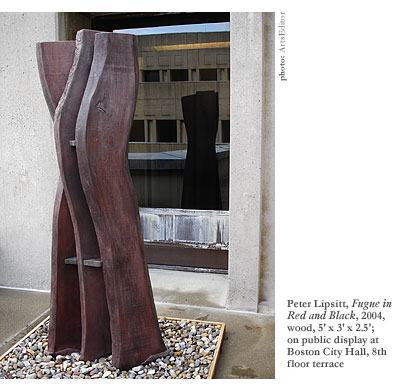

Though the welded steel work he’s done for 30 years and the bronzes he’s made for 10 have always spoken to others, Peter’s new work seems to speak in a different register, if not also to a less intimate power. Take, for example, the tall set of three rough-cut boards, joined by pegs and pigmented rather than varnished, that stand beside but also over their smaller human spectators, like a single upended section of an especially curvaceous staircase. Still retaining bark at the edge and all irregularly milled, these pigmented pine planks have been placed for poetic visual rhythm’s sake parallel to one another, like the intervals of the stride in the freeze-framed limbs of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. This piece maintains the grace and light spirit of Peter’s smaller works—but it stimulates the mind to imagine the rest of a wooden nude abstraction that would be as tall as the four-story buildings of the South End or the ailanthus trees that grow in the tight spaces between them. Like the foot-tall stacks, they could accommodate a grander scale, too—ideally in the imagination.

Many such works by Peter Lipsitt actually have found their way to other dimensions, first in grander incarnations several feet tall, and then out of the traditional venue of the art gallery and into the wider world, in rural outdoor locations in meadows and fields. And when they have, the tarnished bronze cylindrical forms have tended to take on a surprising resemblance to upright tree trunks that have gradually lost their bark and have been treated to the natural, patina-applying power of the weather, the way dead pines with smooth, hard heartwood in New England do. Peter doesn’t make bronze replicas of pine bark to scatter at the base of the trunk or forge woodpecker holes in the higher reaches of the cylinder and give it a yellow patina to make the metal take on the appearance of fibrous pine punk. The suggestion of trunk works more than well enough, abstraction working by indirection to make the metaphoric connection.

As for the new work that is made of actual wood and not metal made to resemble wood, it may be that the 60-something sculptor, till now content to imbue heavy industrial materials with soft spirit, needs to speak less personally now, less consciously about the surrounding crowd of selves. The environmental wood installation called Rhythmic Revolution suggests this especially. A cylindrical construction about the size of a barnyard cistern or a rooftop Manhattan water tank, it’s stained black on the outside and painted a very shady purple on the inside. The upper and lower edges of the cylinder don’t form even seams, of course—like the stacks, this construction is almost but not quite symmetrical. The jagged edges and occasional gaps in the surface of the cylinder keep the eye searching the surface for an entrance and keep the mind curious about the contents of the interior. But there is no entrance to the interior, and the deterrent, black, doorless exterior by contrast makes it even prettier and more interesting in there.

One wonders whether the smaller, three-dimensional, abstract expressions of earthly struggle that Peter Lipsitt has been making for years would venture inside the Rhythmic Revolution if they were granted volition and the power of motion. And one wonders whether what happened to Icarus when he flew too close to the sun—his wax wings melting like the wax inside a clay mold dipped in molten bronze—would also happen to them. And, of course, whether Bashka Paeff would not only know what to make of it but feel as content to remain outside of it as she would be curious to know what it’s like inside.