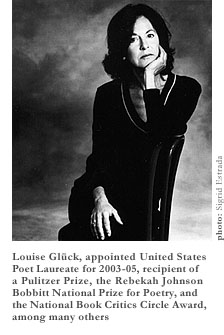

Lit from above by track lights that left the stage of the Sackler Museum lecture hall otherwise in darkness, newly-named United States Poet Laureate Louise Glück looked a little like a high priestess of love, but one who must live always alone for fear of compromising her devotion and losing her enchantment. In a black blouse and short black leather jacket that looks daring on an artist who’s sixty, she kept her focus on the page throughout her usually solemn but sometimes mordantly witty 45-minute reading. Her dark hair hanging in two drapes that kept her quick and quite attractive face mostly in shadow, she fixed her eyes on the text of her own astringent poetry.

In austere measures—in very short sentences—she intoned her disturbingly spare, fearsomely declarative, always disruptive, yet somehow solacing free verse. There was an arresting hush to her delivery, as if the subjects of her poems—erotic anguish, childhood suffering, spiritual agony, familial discord—were a matter, as they are, of life and death. For the content of the eight poems she chose to read to the mostly academic crowd in the lecture hall of the scholarly university art museum, Glück might have been equally at home reading aloud to a crowd of nymphs and satyrs. On some mistier level of consciousness, the track lighting might have been replaced by a beam of full moonlight, pine boughs blown into whisper at the sound of one or another particularly good line. And instead of being practically the least public Poet Laureate imaginable for the federal invitation she’s accepted, Glück might have been one of the Greek goddesses she has made such compelling personal use of in her otherwise extremely current poems, the many collections of which include The House on Marshland, The Triumph of Achilles, and The Wild Iris. But Louise Glück is a mere mortal, and if she wore a laurel wreath it would probably be from Sola in Harvard Square.

In austere measures—in very short sentences—she intoned her disturbingly spare, fearsomely declarative, always disruptive, yet somehow solacing free verse. There was an arresting hush to her delivery, as if the subjects of her poems—erotic anguish, childhood suffering, spiritual agony, familial discord—were a matter, as they are, of life and death. For the content of the eight poems she chose to read to the mostly academic crowd in the lecture hall of the scholarly university art museum, Glück might have been equally at home reading aloud to a crowd of nymphs and satyrs. On some mistier level of consciousness, the track lighting might have been replaced by a beam of full moonlight, pine boughs blown into whisper at the sound of one or another particularly good line. And instead of being practically the least public Poet Laureate imaginable for the federal invitation she’s accepted, Glück might have been one of the Greek goddesses she has made such compelling personal use of in her otherwise extremely current poems, the many collections of which include The House on Marshland, The Triumph of Achilles, and The Wild Iris. But Louise Glück is a mere mortal, and if she wore a laurel wreath it would probably be from Sola in Harvard Square.

True, her reading on that Friday evening in mid-December might have been a turn-off to listeners not accustomed to the poetry of isolation and dread. But to her long-time fans (she’s been on the scene since the 1970s), it was good to hear her fulfill the expectations created in Helen Vendler’s pithy introduction. “She’s never casual,” said Vendler. Sometimes she’s “acid,” at other times “grieving,” always striving to bring human frailty to judgment, clearing her conscience so that she can stand alone in a kind of stricken bliss. Rather than provide a “cascade of images,” Glück sketches only the outline, provides a little moonlighting for it, and fills the scene with fearful consciousness, adhering to metaphysical poet George Herbert’s admonition to prune a tree to make it beautiful.

The mock orange is one such tree, and one specimen is the subject of a poem Glück read. The opening poem of The Triumph of Achilles, “Mock Orange” begins bracingly—”It is not the moon, I tell you./It is these flowers/lighting the yard.”—before continuing famously, “I hate them./I hate them as I hate sex,/the man’s mouth/sealing my mouth, the man’s/paralyzing body—//and the cry that always escapes,/the low, humiliating/premise of union—”.

Acknowledging Vendler’s persuasive critical suggestion to try poems longer than “Mock Orange” or “Gratitude” (from the 1975 collection The House on Marshland), Glück opened and closed with new long work, beginning with a 20-snippet sequence, psychedelically titled “Prism,” that looked in each snippet at a particular refraction of the light of love. “The assignment,” ironically goes the poem by way of refrain, “was to fall in love.” And she did, apparently, suffering a sort of summer heat while the “great plates” of tectonic earth kept “invisibly shifting” under the feet of hapless humans at the mercy of their passions. The two new poems she ended with, “Landscape” and “October,” also managed to describe her very private experiences of romantic and familial love against a vivid if oblique rendering of the larger natural world, in the former with clouds moving symbolically through the poem and in the almost ascetic, litany-like latter with autumn color as a kind of camouflage for the stark display of wild emotion. Somewhere between the lines the importance not just of romantic or familial love but of love of humanity—or if not love of it, then profound sympathy for the difficulty it has in living—sort of oozed into the atmosphere, like an odorless gas that has a narcotic but not lethal effect. Was it good old humanity-hugging agape disguised as skeptical misanthropy—and if so, is that a pretty paradox if the seemingly grumpy solitary turns out, on closer listening, actually to be the anonymous, godlike “somebody” in that Elizabeth Bishop poem who “loves us all”?

In addition to “Mock Orange” and the three new poems of length, Glück read a smattering of other poems from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s collections, including the anthologized classic “Cottonmouth Country,” where she notes that “birth, not death, is the hard loss,” in reference (it would seem) to an abortion; the title poem, a three-strophe ode to childhood loneliness and sickness, of Descending Figure; and the intense, nine-section sequence of lyrics known as “Marathon” that is so private and intimate in the speaker’s address to her lover that we are reminded of Wordsworth’s definition of lyric poetry as “overheard speech.”

It’s hard to say what the highlight of Louise Glück’s reading was. It would probably be fairer, and truer to the thoughtfully orchestrated recital of her poems, to say that the whole reading was a highlight. Or a moonlight, rather.

Cottonmouth Country

Fish bones walked the waves off Hatteras.

And there were other signs

That Death wooed us, by water, wooed us

By land: among the pines

An uncurled cottonmouth that rolled on moss

Reared in the polluted air.

Birth, not death, is the hard loss.

I know. I also left a skin there.

— Louise Glück