Close your eyes. What does the unimpeachable comedy legend Dick Van Dyke of the mind’s eye look like?

It must be the effervescent, tumbling, nimble-like-a-kid, side-stepping, tap-footed, sinewy, husbandly good guy, forever juggling decency and responsibility like a beleaguered, but ultimately prosperous everyman, emblazoned in memory not only because of the quality of his work but of sheer, energetic longevity.

We get it, we see it: in 1960s television and film, no one was lighter on his feet, no one more effortlessly straddling the comedy/elegance tightrope. A song and dance man like Danny Kaye and Ray Bolger before him, a hyperkinetic vaudeville throwback like his idol Buster Keaton, Dick Van Dyke charmed from every angle of the entertainment polyhedron. Those who don’t envision him as Rob Petrie on his wildly popular sitcom likely see him as Mary Poppins’s Bert the chimney sweep, or as his later, nineties television incarnation, Dr. Mark Sloan, on Diagnosis Murder. No need to get nostalgic about his career either— he’s still doing it today, still relevant at 97, whether it’s whooping it up as a gnome on The Masked Singer or nailing down an upcoming guest role on NBC’s forever-running soap opera Days of Our Lives. Matt Shakman, one of the creators and directors of the recent Wandavision, which leaned heavily into the domestic, emotional aesthetic of The Dick Van Dyke Show, put it succinctly in an interview with D23’s Zach Johnson: “Dick Van Dyke is magical.”

Yet often, at the height of their specific powers, comic actors—especially ones who have enjoyed as much sustained success as Van Dyke has—feel the pull of challenging themselves in another gauntlet of performance, the profession as proving ground. If the audience gives even a sliver of merit to the idea that comedy is mined from intimately dramatic events in one’s life, then a comic’s sojourn into weightier material feels like a natural extension of an artistically ambitious career.

What happened, then, in the late sixties, when Van Dyke sought a career chapter akin to James Cagney, a trailblazing triple-threat entertainer who relished dramatic challenges in capital-A acting roles, even wearing a suit or two with shades of villainy? Brief as it was, Van Dyke’s foray into dramatic territory produced a burst of compelling examples of his range and depth from which he summoned an emotional elasticity to match his physical.

After the white-hot success of his eponymous TV show, and the one-two punch of Poppins and 1968’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Van Dyke took a slight tonal detour into director Carl Reiner’s The Comic (1969). Ostensibly a dramatic biopic about the rise and fall of an irascible, egocentric comedy giant, it’s a thinly-veiled account of Buster Keaton’s own rollercoaster career in Hollywood folded into a cautionary, A Face in the Crowd-like fame fable. But as it’s a Reiner vehicle, it never strays too far from a comedic core, even if it affords Dick a chance to flex some more unsavory character traits.

The film opens in the silent film era of Hollywood, and Reiner and his production team authentically recreate the grain and flicker, the movement and feel of early Keaton movies, and it’s one of the best features here (Reiner would later take his affectionate Hollywood recontextualizing to the next level with 1982’s Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid). Van Dyke plays the Keaton surrogate, Billy Bright, a filmmaking comedian at the top of his creative game; he even adopts Keaton’s real-life rasp, a voice unleashed unto audiences when the silent pictures started to talk. The Comic plays with other conventions, too, with one scene mimicking the Citizen Kane newsreel footage of the protagonist’s funeral: “As it must to all men, death came to the King of Comedy, the incomparable Billy Bright.”

Van Dyke is clearly filled up by the role, exerting a performance that feels more reverential to the truth of Bright’s narrative rather than to an embodiment of Keaton’s persona. This is no impersonation and no small feat; it’s also not a stretch to imagine Van Dyke as a legitimate silent film star, a mix of Keaton’s coiled physicality and Harold Lloyd’s lanky grace. The Comic, though, never has the angry, cynical bite that infects A Face in the Crowd—its clear thematic forebear—and it doesn’t allow Van Dyke to reach the sweaty, spitting depths of Andy Griffith’s performance in that 1957 film.

It would be another five years until Van Dyke explored the darker regions of his acting psyche again, and in 1974, he took a plunge into straight-up villainy. That autumn saw the start of the fourth season of Peter Falk’s evergreen TV detective showcase, Columbo; in the year’s second episode, “Negative Reaction,” Dick plays Paul Galesko, an apparently in-demand, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer whose overconfidence after offing his wife will inescapably put him in Columbo’s crosshairs. His character feels cut from any number of smarmy, pseudo-sophisticated, upper-middle-class wanks, the kind that often filled Columbo’s amateur murderer rogue’s gallery. It’s also the kind of role career television actors and movie idols in the twilight of their filmographies dumped onto their resumes by the barrel-full, especially in the dense 70s and 80s arboretum of anthology and “guest-star”-heavy programs.

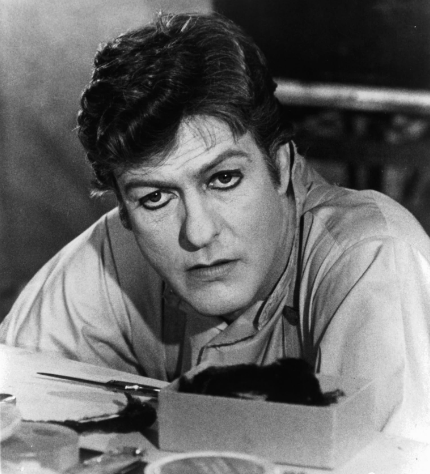

Van Dyke’s turn here is undeniably a kick, though. He tamps down his good guy vibes, replacing enervated bounciness with an exhausted menace, percolating with repressed anger over a wife (played by Antoinette Bower) who runs cold and antagonistic. He also never overplays it, creeping along with an increasing mix of irritability and bravado the longer Columbo natters away at him. And, oh… that beard. Dick’s Tritonesque jawline mane is magnificent in its stark whiteness, flaring out at the sideburns with an improbable part at the chin, not to mention the magnetic chemistry it possesses with the actor’s abundant salt and pepper coif. If Van Dyke was consciously looking to break free from the audience’s preconceived notions regarding his screen image in one fell swoop of a physical add-on, this look is as far away from Rob Petrie as you’re likely to get. In the end, this is also as oily a presence as a Dick Van Dyke character gets; it’s enough to make us pine for the future villainous roles that never came to be.

But just before that gig, in February, Van Dyke spit fire as an alcoholic writer in the made-for-TV movie The Morning After (not 1986’s The Morning After where Jane Fonda spit fire as an alcoholic actress). Although not a 180-degree flip like the Columbo character would eventually be, his performance is nevertheless a slyer, far more honest subversion of his typically ebullient persona, written in part by the storied Twilight Zone scribe Richard Matheson. It’s Christmastime, and a suitably bubbly, Dick Van Dyke-inflected Charlie Lester (sans beard) bounds home to his wife after a surprise boost to his public relations journalism career. He pops some celebratory wine, an argument ensues, and the narrative is in motion: Charlie Lester is—and has been—an alcoholic.

Despite some conventional pacing courtesy of journeyman television director Richard T. Heffron and indulging overwrought tropes (Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday” is the too-on-the-nose needle drop the morning after a big bender), this is still effectively maudlin stuff. Van Dyke’s performance is powerfully lived-in—he’s been candid in interviews over the years about his real-life alcoholism—cannily capturing the charming devil paradox rumbling inside the functional drunk archetype. He’s alternately soothing, cooing, and desperate, making plans for the future while denying what’s happening in the present. In one scene, after Charlie’s wife Fran (Lynn Carlin) has finally left him and his mounting lies behind, he reads aloud from a checklist of alcoholic traits while unsteadily pouring vodka. It’s a harrowing moment, presaging the psychotic episode that will end the story and eschew any attempt at a hollow, happy wrap-up. And it’s Van Dyke’s finest dramatic work to date.

His next attempt at earnest drama would be 1979’s theatrical release, The Runner Stumbles, based on the play by Milan Stitt. In it, he plays Father Rivard, a priest working with the poor denizens of an unprosperous coal mining town in 1911 rural Michigan who falls in love with a new arrival at the parish in the form of vibrant Sister Rita (Kathleen Quinlan). Its narrative ends up landlocked in talky exposition; when it begins, Rivard is already in jail for the murder of Sister Rita and the film jumps back and forth from there to unravel the developing repressed love story/murder mystery. Despite evocative cinematography—like an exceptionally well-lit episode of Little House on the Prairie, and that’s not backhanded—not much else rises above the pedestrian aura of TV-movie staging, this being the last cinematic go-around from the otherwise visually inventive director Stanley Kramer. The film doesn’t commit to either the religious fervor (Ray Bolger does show up as a monsignor, however) or erotic intensity angles, although one unexpectedly tawdry moment comes when Rivard angrily renounces God and auto-erotically chokes Rita before wailing and crumpling in frustrated agony. It’s Van Dyke’s best scene, but The Runner Stumbles could have used more of that dynamism. A beard surely would have helped.

This poses a not entirely irrelevant question: was Dick Van Dyke ever a sex symbol? One could easily imagine Robert Mitchum, who would have been eight years older than Van Dyke at the time of The Runner’s release, or Steve McQueen (five years younger) as Father Rivard instead, two actors who might have brought a higher measure of needed sensual heat to the proceedings. But while a blanket of moodiness and naked stoicism looked real good on those actors, Van Dyke’s deepest appeal has always been his accessibility, his welcoming, disarming visage, and his ability to be present. Is that not undeniably…sexy?

After a stab at serious theater acting with a 1982 TV adaptation of Clifford Odets’s The Country Girl (co-starring Faye Dunaway and maddeningly difficult to track down in this age of YouTube and copious streaming outlets), Van Dyke veered back toward the playing fields and performance textures that suited him best, that provided the foundation for what he did best, injecting his magical alchemy into projects ranging from Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy to Shawn Levy and Ben Stiller’s Night at the Museum films.

And anyone still pondering the question of whether Van Dyke has sex appeal or not need look no further than his original television show and the genuine emotional chemistry that surges between him and Mary Tyler Moore, regardless of whether the chaste network censors ever allowed them to be in the same bed or not. In another TV movie from 1982, the raw, lighthearted Drop-Out Father, Van Dyke’s patriarch character, listens to his daughter laments her grandfather’s fooling around with the housekeeper. “He’s 80,” she says. “People, his age can’t have sex, can they?”

Van Dyke proffers, “Men can do it till they die.” Oh, Rob.

Today, at nearly a century old, Dick Van Dyke—dramatically—may just be at the height of his sex appeal. Look at recent photos of him coolly shrugging off a minor car accident in Malibu and you’ll notice…the beard is back.