If nineteen sixty-seven was ground zero for a tidal shift in American cinema, thanks to the French stepping up their own New Wave game and hailing the movies as a vital and distinct art form, then 1969 took eccentric, elliptical, and experimental narrative and injected it into the veins of mainstream Hollywood filmmaking. That first rush manifested itself in the edgy and meandering, wholly unexpected Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a film that simultaneously ended and ignited eras in the western genre. In its 50th anniversary year, Turner Classic Movies has taken Butch and Sundance on the road (with an earlier stop at Brookline’s iconic Coolidge Corner) as part of their series looking back at that seminal endgame year of the near-apocalyptic ’60s. So, just who are these guys?

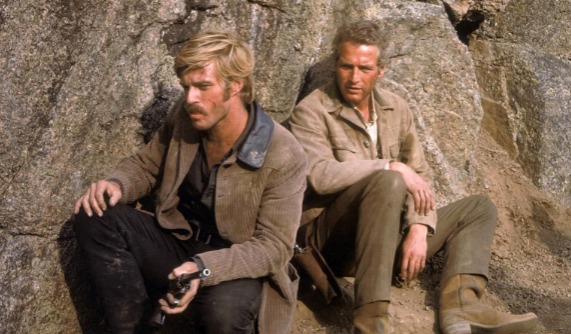

Director George Roy Hill and writer William Goldman’s Butch and Sundance continue to leave a deep mark on American movies, western or not; look no further than Quentin Tarantino’s latest, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood for that nebulous plot (if there even is one), vivid cinematographic patina, and star wattage in the form of Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio, who together vie for the most current incarnation of the easiest pairing of movie stars in history—Robert Redford and Paul Newman. There’s a reason why Butch and the Kid’s much-lauded rapport has maintained its allure for half a century: their onscreen connection is all the more remarkable in that we’re never privy to the origins of the characters’ relationship, denied the foundational connections that first brought Butch and Sundance together. It’s a friendship sustained by mutual respect, as well as a healthy dose of mystery; just as their narrative history is obfuscated from the audience, so they are from each other. It’s almost a quarter of the way into the film before Butch reveals to the Kid his real name; we’re left to wonder how long they’ve actually known each other, or of each other. We’ve been dropped, staccato, into a chapter of their lives, yet Newman and Redford’s earthy, synergistic charisma renders everything that came before irrelevant anyway. The film’s narrative abandons contrived plot points to send the duo hurtling ever forward…away from the forces (Pinkerton-based, Hollywood-based, or otherwise) that would put an end to their story.

The triumvirate at the core of the film, which comes to include Katherine Ross’ Etta Place, is a complicatedly simple one, and a true partnership. Newman, Redford, and Ross pull off a rare feat in film storytelling, too—a mature, faceted bond between three beautiful people where sex isn’t the core component. Yet, the bike ride sequence is as sexy and fun as anything captured on film (and notable in that Newman and Ross’ characters aren’t the ones “romantically” linked). And, oh, the anachronistic music of Burt Bacharach—a revolutionary touch that changed everything (I see you again, QT!).

It’s in the midst of Butch’s eventual crotch-centered takedown of the altitudinous Harvey Logan (played by Lurch himself, Ted Cassidy: “Rules? In a knife fight?”) that Newman and Redford make clear all the narrative—and the audience—needs to follow these two all the way to the end of the line. Preparing for the very real possibility he’ll be dead in a couple of minutes, Butch requests, as any friend bound soulfully to another might ask, that Sundance kill Logan if he loses. Sundance doesn’t hesitate, “I’d love to,” and Redford lifts his vivid, blue-eyed smirk to meet an offscreen Logan, slightly—and slightly menacingly—waving to him.

A friend indeed.