This year marks the centenary of American musical giant—and Massachusetts native—Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), and over 3000 tributes have been planned around the globe to culminate in his birth anniversary on August 25th. I had the opportunity to attend two events in Washington, D.C. on a weekend in May. The foremost question on my mind was whether Bernstein’s larger cultural significance would be accounted for, or whether the potency surrounding his personality and a few of his most popular Broadway pieces would overshadow all else.

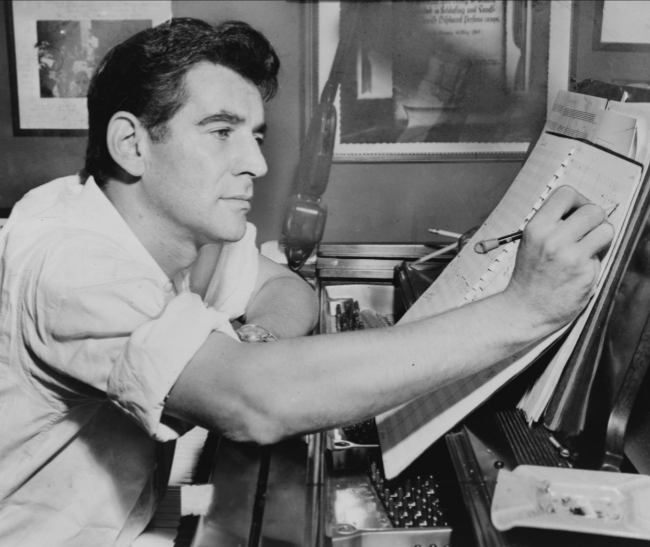

On May 19th, the Library of Congress offered a series of lectures and an accompanying exhibit of Bernstein-related items from its collection. Subjects ranged from “Bernstein and Social Identity” to “West Side Stories” (recounting the creation of the beloved musical) to rare and unpublished piano works. The latter talk was a highlight: pianist Leann Osterkamp both performed and spoke about the harmonically inventive and jazz-inflected pieces, some of which she discovered at the Library. The exhibit included news clippings, scores, correspondence, and a manuscript sketch in Bernstein’s hand of the song “New York, New York,” offering a fascinating glimpse into his creative process.

The following Sunday afternoon, the Washington National Opera presented a gala tribute to Bernstein at the Kennedy Center, a celebration upbeat if not terribly serious. Excerpts from Bernstein’s theater works were presented with barely any context. Musical numbers were interspersed with comments from WNO and Kennedy Center officials that at times resembled infomercials. Baritone Nathan Gunn acted as an MC for the event, Bernstein’s daughter Jamie made some pertinent remarks about her father, and Broadway star Patti LuPone sang numbers from West Side Story and On the Town.

Oddly enough, the vocal highlight of the gala came not from LuPone but from two fine young opera singers, both by a curious coincidence named Leonard. Isabel Leonard displayed her lush, evenly produced mezzo-soprano in “Take Care of this House,” a gem of a song salvaged from the 1976 musical flop 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. And soprano Madison Leonard—a finalist in the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions—brought insouciant charm to selections from I Hate Music: A Cycle of 5 Kid Songs.

These events failed to offer any idea of Bernstein’s larger cultural significance, leaving me to sort this question out for myself. I admit to being a tough customer in this area: I’m perennially skeptical of celebrity worship when it comes to arts figures.

Any assessment of Bernstein must take into account that he was many different things: a Broadway and classical composer, a conductor, a lecturer and a television personality. Bernstein’s career was a juggling act of musical activities, and he was not always able to find the perfect balance. Some critics maintain that his Broadway efforts detracted from the time and energy he could have devoted to composing symphonies. Others think he simply lacked the range and originality to produce a substantial body of accomplished concert music. Even so, such works as Serenade after Plato’s Symposium and Chichester Psalms, along with one or two of the symphonies, have stood the test of time and entered the active repertoire.

Another of the many “hats” Bernstein wore was that of a conductor who invariably brought an electric spark to his orchestral performances. From his short-notice substitution for an ailing Bruno Walter at the helm of the New York Philharmonic in 1943, Bernstein shot to fame and remained in demand as a conductor of the world’s leading orchestras. Although his front-and-center personality and emotionalism were not equipped to every taste, he always made a statement, and nothing was half-hearted. His recorded legacy is ample, and he is considered by some critics to be the greatest conductor of American origin.

Although not all of Bernstein’s compositions speak to me—and I find his later embrace of trendy politics regrettable—I can’t help admiring the ingenuity and craftsmanship of his best work, whether for the concert hall or the Broadway stage. Lest we forget, Bernstein’s roots were in the Boston Neoclassical school, derived from Harvard and the teachings of Nadia Boulanger. That training shows in a piece like the Act I Finale of West Side Story, where Bernstein weaves the diverse emotions of the characters into a contrapuntal tapestry of operatic proportions.

Surprisingly—and I was not aware of this until Leann Osterkamp pointed it out—Bernstein didn’t begin formal music study until the age of 14, after coming of age on a mix of classical and popular music on radio and records. This eclectic background enabled him to become one of the first “crossover” composers, bridging the Broadway and classical worlds. His popular touch made him an ideal public spokesman for classical music, explaining its intricacies to a whole generation in his televised Young People’s Concerts. Many of those young people, in turn, grew up to become avid patrons of classical music.

This, I believe, is Leonard Bernstein’s true legacy: his gift for communication—whether through his conducting, his friendly yet erudite lectures to young people, or his theatrical pieces which blended “serious” and “popular” without condescension. As classical music lost ground to rock and pop in American culture, Bernstein helped keep it alive and relevant through his passion, intelligence, and personal magnetism. He gave classical music both a lifeline and a shot of adrenaline. For this rare gift, he will be remembered and celebrated, not just in his centenary year but for all time.