In that oft-quoted epiphany from Walden, Thoreau announced that he’d gone to the woods to live “deliberately,” so that when it came time to die he wouldn’t have to look back and sigh at the missed opportunity. That’s pretty much why soprano Rebecca Hayden, already in pursuit of what has turned out to be a deeply satisfying high school English teaching career in the Boston area, decided more than a decade ago to confront her deadliest demon, stage fright, and see if she could get some solo work in oratorios, operettas, musicals, and the like. She wanted to see if she could get up the nerve to embark on the supplementary singing career that takes up much of her spare time.

“I just had to get over it,” she says now, rummaging through old journals in search of the one she recorded her resolution in on her 30th birthday. “I didn’t want to end up hiding in choruses forever, and I knew that I had at least a moderate amount of artistic talent to offer. I just couldn’t justify not making a go of it!”

She knew it wouldn’t be easy to get a cure for the case of stage fright she’d incurred in adolescence. Maladies like that don’t disappear like acne. And she knew it would be hard to get good solo gigs in a town like Boston, arguably the classical music capital of the country, that turns out to be even more glutted with skilled musicians than she feared. Home not only to the legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra, but also to star conductors like Ben Zander, Craig Smith, and David Hoose and to a number of top-notch music schools (including the ones at Boston University and the New England and Boston Conservatories), this area attracts ambitious musicians from the provinces by the busload. (Boston’s also known as the absolute center of the early music universe, even; and it’s not bad for rock and jazz players either.) And that includes vocal musicians. When the musical market is almost as tight as the housing market, a local star like baritone Robert Honeysucker “gets his pick of the third-tier operettas and oratorios between his appearances in the first- and second-tier productions,” notes Hayden. Which leaves the well-trained, earnest, and moderately gifted third-tier talents (whom she counts herself among) wondering if they should go back to Nashua and Laconia and be big fish in small ponds.

She knew it wouldn’t be easy to get a cure for the case of stage fright she’d incurred in adolescence. Maladies like that don’t disappear like acne. And she knew it would be hard to get good solo gigs in a town like Boston, arguably the classical music capital of the country, that turns out to be even more glutted with skilled musicians than she feared. Home not only to the legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra, but also to star conductors like Ben Zander, Craig Smith, and David Hoose and to a number of top-notch music schools (including the ones at Boston University and the New England and Boston Conservatories), this area attracts ambitious musicians from the provinces by the busload. (Boston’s also known as the absolute center of the early music universe, even; and it’s not bad for rock and jazz players either.) And that includes vocal musicians. When the musical market is almost as tight as the housing market, a local star like baritone Robert Honeysucker “gets his pick of the third-tier operettas and oratorios between his appearances in the first- and second-tier productions,” notes Hayden. Which leaves the well-trained, earnest, and moderately gifted third-tier talents (whom she counts herself among) wondering if they should go back to Nashua and Laconia and be big fish in small ponds.

Which isn’t to say that Hayden’s solo singing career has been limited to her shower at home. (Medleys of arias, art songs, and American popular songs performed for the pleasure of her upstairs neighbors and her nearby husband.) The risk she took (of crushing humiliation and disappointment) has paid off handsomely—or at least with good enough looks to get by. Since making that resolution at age 30, she’s been the comical lead Rose Maybud in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Ruddigore and the also comical second lead Bianca in Cole Porter’s Kiss Me Kate at the Arlington Street Church, where she’s also soloed in a First Night performance of Johann Strauss’ Die Fledermaus. She’s done three programs of popular American and classical European art song at three separate locations—the Newton Free Library, the University of Maine at Farmington, and the Orchard Cove Assisted Living Center in Canton, Mass—and additional solo recitals for the Somerville Museum, the Waltham Public Library, and the Salisbury (Vermont) Summer Series, among others. (Her piano accompanists, for the record, have included Michael Strauss, Pamela McClain, and her stepmother Patricia Hayden; she nods to former teacher Jayne West and to close friend and fellow singer Karen Bell for encouraging her efforts; and she credits Boston University music professor Mark Aliapoulis with “teaching me to sing correctly, so that I could literally find my voice and get over my stage fright.”)

There’s the steady church work she’s gotten at St. Peter’s Episcopal in Weston, the Pleasant Street Congregational in Arlington, and the First and Second Church on Marlborough Street in Boston—all of these paid jobs—and the short-term singing stints she’s had (enough to whet her appetite and make her pine for more) for such first-rate Boston-area choruses as the Cantata Singers, the John Oliver Chorale, and the Tanglewood Festival Chorus. There are the several years she spent in Chorus Pro Musica, singing such works as Vaughn Williams’s Sea Symphony and the Brahms Requiem in Jordan Hall. And the year she spent in the Munich Bach Chorus when she was in a teacher exchange program. And even though this resumé of achievements would make some sopranos think they could now die at peace, Hayden longs for more than the occasional recital or choral part. “I just want a steady musical life,” she says.

“I don’t expect to make a career of it,” she explains. “I just love singing. I love teaching English too”—a solo performance of another sort, to be sure—but singing satisfies her in a whole other way. “My whole life feels balanced and makes sense when I sing. The white noise goes away.” Even in a city of what she modestly calls “much more talented musicians than me, I have a voice that I need to share.” It’s an integration of spiritual, aesthetic, and physical elements, she says. Given her erudition and concerns of social conscience, one might hasten to add the ethical and educational elements as well.

The performance itself is the most elevating part of the life, because that is where all the preparation comes together. Still, the pleasure Hayden takes in singing can be witnessed in a nosy observation of her practicing in her home. There she is now, a short, perky, well-toned woman with a sandy, somewhat befreckled complexion, nape-length auburn hair, green eyes, an oval face (with a long and shapely nose), and a housecleaning outfit of t-shirt and running shorts. It’s late Saturday morning, an hour or two before the noontime opera broadcast from the Met comes on, and she’s standing over her piano in her parlor in Cambridgeport, her right hand striking the chord for her voice to live up to, her left hand climbing or descending the scales or going up and down them as the score on the music stand mandates. She wears a pencil behind her left ear (because she’s left-handed) for making notes on the score. Starting a phrase—then stopping to clear her throat and throw off a somehow uncharacteristic little curse for good luck—then starting it back up from a slightly different place, she sings through a phrase or two, then backs up and starts it again, this time going another phrase or phrase-and-a-half further. It is obvious that she is trying to blend the most distinct, accurate expression of the lyric with the most precise diction, with her better, clearer, disembodied high notes creating plumes and flumes in the bright parlor air that you can almost see. It’s a process not just of memorization but of breathing her own authentic life into the prescribed form. In that way maybe this discipline resembles glassblowing. She smashes each test glass into slivers until she gets it right.

To see how it might have occurred to someone to choose classical vocal music as her dominant form of artistic expression—rather, say, than glassblowing—you can leave her parlor. (She won’t notice; she’s learning a new song cycle by Rodrigo or Poulenc, or going back over some of the stuff she used to do by Copeland or Gershwin, in preparation for an audition or a recital.) You can check the dark shelves of the tool hall at the wooded end of her family’s hillside summer house in western Maine, over there in the far corner, to the right of the monumental hearth of native fieldstones. That’s where the mice-nibbled, time-browned albums of classical 78-rpm music remain more than 50 years after her grandfather’s stroke put an end to the soirees he and his wife hosted for their friends during his summer vacations. The dalmationed victrola on which they played the complete sets of Beethoven symphonies, Bach cello suites, and Mozart operas is gone. But in the other corner broods the abandoned stand-up piano, damaged beyond repair, the few keys that still respond to the touch able to do so weakly, with sickly, out-of-tune sounds that remind you of what it must have been like to speak with the once-dynamic grandfather after he’d had his stroke. Nothing remains of its formerly upright character and expressive tone. There’s little response to your press of the keys.

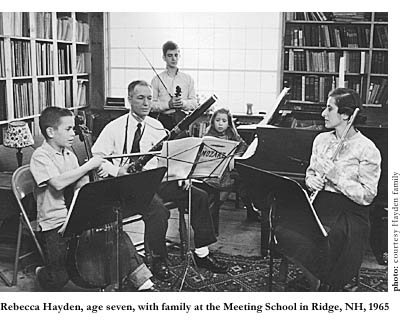

Hayden was born into music, in an immediate family that (including her New York Jewish mother) practiced an avid, if progressive, form of Christianity. Her father, Joel Hayden, used to play that piano with lots of gusto and very little inhibition when she was growing up in New Hampshire and Maine and able to spend long summery stretches at that summer house in the 60s and 70s. He had learned his taste, if not his chops, from those stately and established 78-rpm monuments of high European culture. He loved the mathematically marvelous notational architecture of the Baroque, the joyous and God-exalting sounds of the classical era, and the brave, thunderous, nature-nurtured storms of the Romantic era. (He didn’t care for much if any of modernist music that strove to describe and mimic the unpredictable, ephemeral, disturbing aspects of earthly existence.) But his Quaker-spun, American-born civil rights concerns had brought him to appreciate, and even to imitate, the Negro spiritual and the folk song. When he wasn’t conducting a community chorus (her participation in the Monadnock Community Chorus of Peterborough, New Hampshire, is Hayden’s earliest musical-performance memory) or composing a somewhat anachronistic oratorio with 18th Century leanings, he was writing witty rounds (a cappella ditties for multiple voices) or occasional quasi-Gospel songs in brazen, some would say naive, praise of the Almighty. Or he was gathering the whole family into the parlor of their 18th Century house (with a view of Mt. Monadnock) for a Sunday afternoon session. He played piano and bassoon, Rebecca’s mother played flute, her brothers played violin and cello, and everybody sang.

“I lost my faith a long time ago,” Hayden says of the religious (albeit unorthodox and in some ways downright countercultural) upbringing. “But I find it again through music, and especially through singing.”

Some of her inspiration and a good deal of her aspiration can be attributed to her experience in the late 70s with experimental music at Wesleyan University, a school known for its adventurous ethnomusicologists and authentic international faculty musicians, for which Wesleyan might rightly be called a breeding ground of world music. Neely Bruce, the flamboyant Alabamian who has conducted the Wesleyan Singers for years, turned Hayden’s attention to a wider range of music than she had been exposed to in the Great Works repertoire of her father. “I’ll never forget when Neely said, at our first chorus rehearsal freshman year, that we were going to perform Wobbly music on our tour that fall. I thought he meant some kind of atonal music that sounds warped—not the music of the Bread and Roses millworker unionists up in Lawrence in 1912!” The Wesleyan Singers did a whole concert tour that fall concerning the vision of America as the new Utopia, including Sacred Harp “shape-note” music, abolitionist songs from the ante-bellum North, and the aforementioned Wobbly music. Later they did a three-hour environmental piece by Pauline Oliveros titled Rose Moon, in which Bruce and his wife sang in the nude, from behind a suspended sheet. “Oh, we did everything,” she remembers. “Israel in Egypt, a Baroque oratorio by Handel; the opera Dido and Aeneus, by the 18th Century British composer Purcell; Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms; even a sardonic treatment of the unintentionally comic Robin Hood—a sort of bad Gilbert and Sullivan.”

Nowhere on Rebecca Hayden’s musical resumé does it say that she got to perform in Hair between her sophomore and junior years of high school at the UNH summer theater; nor that she had a solo in George M! late in high school in Sanford, Maine; nor that she sang a soaring devotional song from the organ loft at her friend’s church wedding in New York City last spring. (Not a word about the solos she did at another friend’s wedding in New Hampshire last fall either.) It doesn’t even say that she spent a year in the gospel choir of Boston University during one of her two years of grad school there—but she did, and there’s that spiritual connection again. “I believe that spiritual and aesthetic impulses stem from the same mysterious source in humans,” she says. “I guess that’s why, if I could be reincarnated as a great singer, I would not be an opera star at the Met. I’d be a great black gospel singer, with an instrument that could do anything. When I sing those words of praise and redemption, I believe them.”