I can’t remember the exact title of the book—something generic like The Art of Living—nor the transliterated Chinese name of its author. It may have been a translation of an earlier-20th Century authentically Asian self-improvement manual. Blissfully lacking the upbeat, clean-cut, oh-so-practical jargon of the American human-potential pushers, it was a simple and serene synthesis of Chinese philosophy—a mix, maybe, of the social Confucian and the solitary Taoist. Figuratively it occupied the plywood shelf above the one, in the early 1970s student apartment, that supported the Carlos Castaneda books about Mexican peyote mysticism, the J.R.R. Tolkien trilogy about the otherworldly creatures who inhabit Middle Earth, and the pious parchments of Kahlil Gibran poetry.

One of the chapters in that misplaced and underappreciated book argued calmly for the use of loose suspenders over tight belts. I think another recommended in detail a fresh diet of natural foods, low on meats and stimulants and high on indigenous produce. Still another I think must have sung the praises of honesty and seriousness in all human relations, in a voice leavened by levity.

But the best chapter, the one I most vividly remember, they used to reprint in college-level freshman composition anthologies of excellent exposition. A couple of thousand words long, it made a beautifully encouraging case for the importance of art-making to the spiritually healthy adult life. Assuming that anyone could do it without waiting for a call from the deities, the contemplative philosopher said that the urge to make songs, poems, pictures, and statues (and, by extension, perishable mixed-media assemblages) flows naturally from a joyful person, like water from a woodland spring when the aquifer is full. Art is a kind of therapeutic recreation for the psyche, he insisted: the expression of excess energy that festers and fritters and causes blurred vision and cognitive confusion if wasted, for instance, on the watching of television. Art (to use that little big word again) can be made in an ordinary citizen’s spare time, in a studio that is to the artist what the shaded sandbox is to the summertime child.

How much spare time is necessary for the production of paintings, photographs, poems, and the like? Are weekends enough? How about the three paltry annual weeks of vacation so graciously granted the more or less average American worker? After the groceries have been gathered and the floors have been swept, can the practical proletarian, public servant, or workaholic portfolio consultant find the inspiration to get out the guitar or prepare the palette? Doesn’t the laundry have to be done and the bed have to be made first, or lain down in with a lover for some other, more basic, yet nevertheless sustaining recreation?

The encouraging answers to these questions—and the long-delayed subject of this article—in March and April are decorating the walls and pedestals of the first-floor art gallery at the Boston Arts Academy, a public high school that has occupied the bland old brick building outside of Fenway Park’s right field bleachers (the former site of the Boston Latin Academy) for three academic years or so. That’s where a dozen hard-working teachers (who have the summer off, by the way, and several intervening vacation weeks) from Boston Public Schools all over the city are exhibiting the painstaken products of their own excess energy.

Fittingly called After Hours, the show at the BAA includes such highly crafted, representational, pleine aire paintings as Richard Roche’s stricken Goshen Farmhouse, haunting in its abandonment in autumnal afternoon light; Beth Balliro’s watery landscape of an Essex Salt Marsh, solemn in its subtle study of flat horizontal forms on a laterally elongated canvas; and Maurice Lane’s Santorini, appetizing in its sunstruck view of a blue-and-gold Mediterranean bayscape seen from a shaded balcony. These accomplished, finished, earnest paintings are the admirable result of attentive training, ardent apprenticeship, and psychically involved work with the brush and tubes and canvas. They’re more likely to sell at the Rockport wharf or in Newbury Street gift galleries than they are to wind up in the MFA’s darkened, permanent, basement collection. There’s a sense that they didn’t part easily from their easels when finished, but fought for the right to be propped up there in the natural light a little while longer.

That same trustworthy mainstream appeal—affectionate and honest rather than irreverent and affected—is evident in the several other more traditional, “workmanlike” pieces in the show. Guy Michel Telemaque’s landscape photo of Sandy Pond by the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park in Lincoln ripples and blurs the view of the water through the trees, as if looking through the water itself, and in a painting rather than a photograph. The blaze of autumnal color in the background is barred and defined by the slender verticality of the tree trunks in the foreground. This photo shares the front of the publicity postcard with Balliro’s painting of the marsh. Water, water everywhere.

In a public high school, it’s tempting to measure the artwork of teachers against the virtues we expect from such public figures: accessibility, diligence, perspective, liveliness, balance, levity, and faith in ordinary beauty. And that’s what we get here.

Like seven of the 22 artists exhibited in the show (including Balliro), Telemaque teaches right there in the Boston Arts Academy. So does Roberta Phillips, director of the BAA’s gallery and creator of Eulogy for my Father, a large celebratory collage of dark geometric construction-paper cutouts and a couple of family photographs—one of the artist (presumably) aiming a camera across the wide expanse of the collage toward her elegant sunglassed father posing for a photo in some sunlit urban plaza or other.

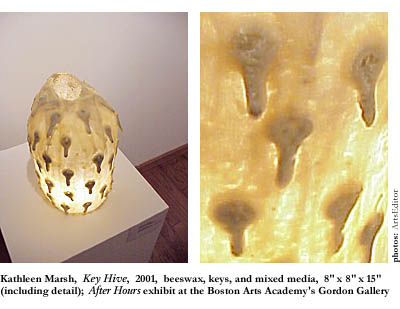

The maker of one of the edgier pieces in the show, Kathleen Marsh, teaches there too. Marsh’s punny three-dimensional piece, Key Hive, is a functional, freestanding lampshade made of screen that first has been formed in the shape of a beehive you’d find in the crotch of a honey locust tree and then applied thickly with beeswax. Embedded in the surface of the thick, sickly golden wax are ordinary, roundheaded house keys, in the sort of symmetrically staggered wallpaper pattern you’d expect to find the identical, mass-produced images of a Civil War cannon, say, in the shade of a boy’s bedside lamp, or images of garden flowers in the shade of a girl’s. There’s a light switch nearby, and there’s a lightbulb inside that goes on like the bright idea this funny sculpture is.

Wanda Crayton’s leathery brown mask, Mr. Blue, woven of jute and hung from the neck with beaded blue strings, postmodernizes (if you will) the Picassoesque appropriations of African art that it owes a tribute to. The black-and-white mock-medieval-moralism prints of Helen Corsi—He Who Goes to Deceive Will Remain Deceived and Everyone Wants Her But No One Will Take Ms. Camilla—are themselves appropriations of historical sources, as European as Crayton’s are African. Amy Sallen’s The Nest, though, is harder to place. (No need to anyway, really.) A large oil painting of cryptically symbolic elemental images, it features a paganistic middle-aged woman in a comfortable dark pajama-like outfit kneeling among some scattered rubble in a kind of enchanted desolation before the bent stalk of a golden autumn wildflower, goldenrod or mullein, her bespectacled eyes closed, her red hair thrown back, her arms raised to receive some deadly power, perhaps, that the gull in the lower foreground and the blackbird on the bent stalk so calmly and starkly contain. A nice big ambiguously allegorical picture; it reads like a poem.

There’s plenty more to look at in this show, and it represents, predictably enough, a good variety of styles and influences.

Sharon Pierce’s boxes do not harken back to Joseph Cornell as they might suggest. But it is a pretty thoroughly post-WWI conceptual piece, recalling Dadaist exercises in freeing mysterious unconscious images. The four square painted-plywood boxes, perched one on top of the other on two pedestals of unequal height, pique curiosity and invite speculation. The top box of each pair does not sit squarely on top of its partner but at an angle. In one side of each box is a pinhole aperture through which (once the box’s respective light has been switched on) can be seen the interior of the box. In addition to a light, Pierce has installed in each box a dollhouse room, but not the kind Barbie would have liked. Sparsely furnished with a chair (or, in one case, a crib), each room (thanks to a trick done with mirrors) has a distinct shadow falling across it and a partial side view or complete silhouette of a somewhat pinched figure around the corner in another room. Quirky. Mysterious. Ominous. Funny.

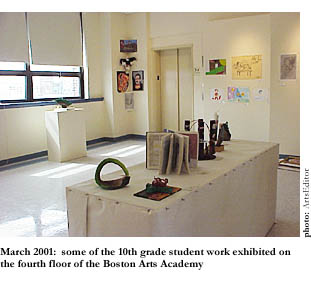

Varying in medium and message, the pieces in this show look like polished, professional responses to the sorts of assignments the Boston Arts Academy visual arts teachers have given their 10th-grade students this year, the results of which are on display in the hallway outside of the fourth floor elevator, overlooking the right field wall (and the legendarily creatured bleachers) of Fenway Park. Up there in the real world where the high school students work, the walls exhibit the oiled diptychs, penciled portraits, and clipped and scissored collages the students have done, while the pedestals in the middle of the room exhibit the three-dimensional “monuments” they’ve built. There’s talented Deborah Browder’s surprising sculpted hand, for example—each finger of which is a nightlit high-rise apartment tower—and there’s Lydia Kardos’ poetic diptych of her grandmother, featuring on the left the distinguished woman in glasses and white shawl and on the right a painting of the younger woman done, no doubt, from an old photograph. Juan Gonzalez’s satiric collage commentary on desolate urban orderliness. India Perryman’s crucificial tiger sculpture. And a 3-D representation of Fenway Park itself, by a young man named Orlando.

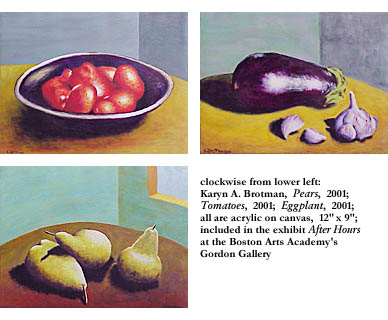

But back downstairs, there’s still more of the teachers’ work to see on the way out. Karyn A. Brotman, also of the Boston Arts Academy, has three small and excellent still lives in the show, Eggplant, Pears, and Tomatoes, done in sensuously thick and true-to-the-produce pigments that convey a combination of the sinister and the stable. The greenish-yellow pears and the deep red plum tomatoes tell us about grouping and gathering, and the purple eggplant about solitude and space. The same table in each must tell us about stability; and the same corner of blue walls in each about comfort and contentment. But the vivid colors tell us about the surging urges of life.

Yes, Barrington Edwards works at the BAA, too. His exuberantly sloppy and informal drawing, the punny and irreverent Revolution, done (according to the jesting caption) in “daffodil juice on wallpaper” (or what looks to be the plastered backs of newspaper-sized advertising circulars), speaks for the alternative school’s politics. Seven chimps are engaged in various automated learning tasks in a lab-like classroom, apparently preparing to take the controversial, standardized MCAS test (Massachusetts Comprehensive Achievement System) that kids from the commonwealth now must pass in order to continue from grade to grade. The chimp in the foreground (occupying a large portion of the picture plane) reads a large manual about “How to Pass the Frigging MCAS and Other Useless Trivia.” (But MCAS doesn’t stand for Massachusetts Comprehensive Achievement System here. According to the manual’s cover, it stands for Monkeys Can Academicilee Survive.) Another behavior-modified chimp in the background watches a senselessly cheerful Pollyanna newscaster lady, a picture of exacting primness and perfectionist efficiency, deliver her morning-news lines—about murder and mayhem or the sins of our great celebrities, probably. (It’s not a blatant suggestion about the media’s transferal of bankrupt middle-class values, is it!?) The other chimps paste letters of the alphabet into a book, sit in a counseling session with four faceless authority figures in labcoats, or stare dopily at computer screens. None of them seems to be accidentally composing that Shakespeare play someone said they might someday if they sat there typing long enough. A polemical cartoon, Revolution relies on verbal as much as pictorial humor, and it speaks for the position of the progressive, anti-standards pedagogy of the Boston Arts Academy, a portfolio- and project-based school that, rather than measuring the worth of students from an authoritarian height, encourages the students to rise to their own academic and aesthetic potential.

Yes, Barrington Edwards works at the BAA, too. His exuberantly sloppy and informal drawing, the punny and irreverent Revolution, done (according to the jesting caption) in “daffodil juice on wallpaper” (or what looks to be the plastered backs of newspaper-sized advertising circulars), speaks for the alternative school’s politics. Seven chimps are engaged in various automated learning tasks in a lab-like classroom, apparently preparing to take the controversial, standardized MCAS test (Massachusetts Comprehensive Achievement System) that kids from the commonwealth now must pass in order to continue from grade to grade. The chimp in the foreground (occupying a large portion of the picture plane) reads a large manual about “How to Pass the Frigging MCAS and Other Useless Trivia.” (But MCAS doesn’t stand for Massachusetts Comprehensive Achievement System here. According to the manual’s cover, it stands for Monkeys Can Academicilee Survive.) Another behavior-modified chimp in the background watches a senselessly cheerful Pollyanna newscaster lady, a picture of exacting primness and perfectionist efficiency, deliver her morning-news lines—about murder and mayhem or the sins of our great celebrities, probably. (It’s not a blatant suggestion about the media’s transferal of bankrupt middle-class values, is it!?) The other chimps paste letters of the alphabet into a book, sit in a counseling session with four faceless authority figures in labcoats, or stare dopily at computer screens. None of them seems to be accidentally composing that Shakespeare play someone said they might someday if they sat there typing long enough. A polemical cartoon, Revolution relies on verbal as much as pictorial humor, and it speaks for the position of the progressive, anti-standards pedagogy of the Boston Arts Academy, a portfolio- and project-based school that, rather than measuring the worth of students from an authoritarian height, encourages the students to rise to their own academic and aesthetic potential.