Photography in Boston: 1955-1985 is a joining together of science and art, detailing the tangent line at which these two points meet. The work showcased is a coming together of schools of thought, as with Minor White’s “Zen” system compared to Ansel Adams’ “Zone” system. The thirty years addressed comprise the flowering of a community of artists, scientists, and writers (with these classifications often overlapping one another) that, prior to 1955, lived in a “wasteland,” as described by writer/critic A. D. Coleman. There was no voice for this shared craft of photography. This catalogue pays homage, then, to the innovators of photography in the Boston area and their contributions to the art.

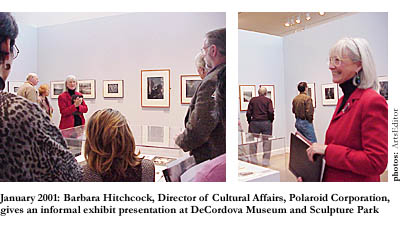

Kim Sichel and Rachel Rosenfield Lafo open with their dual commentary on the thirty years spanning the growth of photography in Boston and surrounding areas. Lafo, Senior Curator, and Gillian Nagler, Curatorial Intern, are co-editors of the catalogue, accompanying an exhibition which was held at the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park. Lafo explains why these years in particular were selected: “The thirty-year period chosen for this project encompasses photography’s acceptance as an art form, the influence of modernism, and the coalescence of a unique constellation of educational institutions, museums, and technological developments in the Boston area that directly influenced artistic options for photography.” Sichel continues along this line with her essay “Science and Mysticism,” which details the years 1955-1970 and intersects two seemingly disparate elements of photography. “These realms met in unexpected ways:” Sichel writes, “the scientific community’s work shared many artists’ wonder at nature’s beauty, while the artists conducted their personal explorations through a series of highly detailed and crafted technical innovations.”

Kim Sichel and Rachel Rosenfield Lafo open with their dual commentary on the thirty years spanning the growth of photography in Boston and surrounding areas. Lafo, Senior Curator, and Gillian Nagler, Curatorial Intern, are co-editors of the catalogue, accompanying an exhibition which was held at the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park. Lafo explains why these years in particular were selected: “The thirty-year period chosen for this project encompasses photography’s acceptance as an art form, the influence of modernism, and the coalescence of a unique constellation of educational institutions, museums, and technological developments in the Boston area that directly influenced artistic options for photography.” Sichel continues along this line with her essay “Science and Mysticism,” which details the years 1955-1970 and intersects two seemingly disparate elements of photography. “These realms met in unexpected ways:” Sichel writes, “the scientific community’s work shared many artists’ wonder at nature’s beauty, while the artists conducted their personal explorations through a series of highly detailed and crafted technical innovations.”

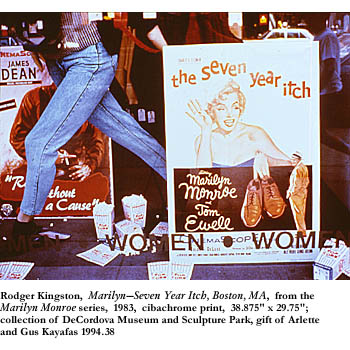

In Sichel’s essay, one encounters the scientific influences of Dr. Edwin Land and Dr. Harold Edgerton, developers of the Polaroid process and stroboscopic photography respectively, along with Minor White, an MIT professor who “combined formal experimentation and mysticism, and engaged whatever philosophical method opened his own mind or those of his students.” A number of photographers highlighted are from his circle of colleagues and students, such as Peter Laytin, Jonathan Green, Gus Kayafas, Carl Chiarenza, and Paul Caponigro. Lafo continues the commentary with her piece “Expansion and Experimentation.” Beginning with 1970, photography’s burgeoning presence extended outward from the scientific and artistic realms within which it was once nourished. Photography became omnipresent, especially in the Boston area due to the large number of resources that fostered both the production and use of photographic materials and, subsequently, artistic expressions. From the 1970s, photography garnered recognition in the “genres of documentary photography, the vernacular and formal landscape, the social landscape, autobiography, constructed images, and experimentation with alternative processes [which] were all still being practiced in 1985, and continue to this day.”

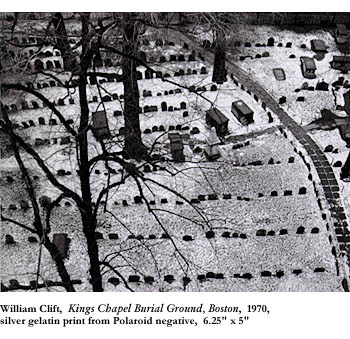

Then there are the photographs themselves. This compilation serves as a well-planned introduction to Boston-area photographers that does not inundate the reader/observer with too much information. All works are from this family tree of Boston-based scientists and artists, whose interconnectedness helps one visualize a virtual timeline of dates and names. As with the diversity of the contributors’ backgrounds discussed in the introductory essays, the photographs selected provide that same range of styles and transport one through the initial thirty years of Boston-based photography. To say that one sees advancement in the images, as if the preceding photograph is outdone in artistry and technical craftsmanship by the next photo would be wrong. All the works are solid pieces regardless of the time from which they come. That is why this period is unique in terms of advancing the artform as a whole. Here one sees the exquisite Milk Drop Coronet on Red Tin by Harold Edgerton from 1957. The precision and detail of his work, along with the simplicity of the image intermingle with the scientific quality of the piece. From the 1960s, there is Jules Aarons’ well-constructed Indian Boy, Quito, Ecuador of a young boy in a rough-hewn poncho, leaning and looking towards something outside of the photograph’s frame. Kim Sichel observes that “his luminous eyes and tilted hat [are] in strong juxtaposition to the tactile pattern of the masonry behind him.” With Hakim Raquib’s Zeigler Street from 1970, shadow and light are presented in a striking, yet subtle way, with the sunlight playing off of the faces and clothing, accentuating profiles and the folds in their coats. Ome, by Rudolph Robinson in 1983 again employs this quality of light with a stark image of a boy sitting off center, partially under lamplight and in darkness.

All of these examples share in common an elegance of composition that transcends the decades. As with the entire compilation, the photographs incorporate elements of simplicity. From Berenice Abbott’s Magnetic Field, which demonstrates a scientific phenomenon to Daniel Ranalli’s Bird Fetish #1, a photogram that utilizes the science of photography (similar to the idea behind MIT’s Gyorgy Kepes’ 1951 exhibition The New Landscape that “[combined] abstract images with those of scientific phenomena such as photo and electron micrographs. Its subject was the ‘new frontiers of the visible world…until then hidden from the unaided eye’.”) In Kepes’ Untitled, one sees a plane of intersecting lines crossing over flames, sparse in design, yet innovative in technique. Berenice Abbott, another MIT scientist/ researcher, says, “Here in physics is primal order and balance; its universal implications extend limitlessly. Both scientists and artists are humble before its reason and proportion. Both try simply and faithfully to express the subject. Both must know above all else how to let the subject speak for itself.”

Boston, then, was an ideal setting for such expression. A. D. Coleman in the third essay, “Writing and Publishing about Photography in the Boston Area, 1955-1985,” theorizes that “the city and its outlying territories contained an unusually high concentration of colleges, universities, and other institutions of higher learning,” MIT and Boston University, along with RISD in Rhode Island, being some of the most prevalent in fostering the research and accessibility for the growth of photography. Coleman continues, “It had (for a North American metropolis) a long and rich tradition of cultural and intellectual life…and a social context in which informed attention to the visual arts generally had established itself as an accepted aspect of the life of the mind and the enjoyment of the cultural milieu.”

Concluding the catalogue is Arno Rafael Minkkinen’s essay “Thirty Years of Polaroid Photography in Boston,” acting as a tribute to Dr. Land and his creativity. Minkkinen writes, “Polaroid is renowned, of course, not only for encouraging its products to be used in nontraditional ways but for standing behind the pioneering exploits of its practitioners. Through its exhibitions, publications, and collection purchase policies, the company has demonstrated an astonishing aesthetic flexibility.” He continues, “In a time of tightening censorship in America, Boston photographers found aesthetic shelter with the Polaroid corporation.” Along with Minkkinen’s own commentary on the Polaroid Corporation and its contributions to artistic expression is a series of personal interviews he conducted with fellow photographers, such as Paul Caponigro. Caponigro was recommended by Ansel Adams to be a consultant for Polaroid, testing out its products. It is Caponigro’s final statement that best summarizes not only the feeling of freedom afforded by Polaroid films, but freedom in photography in general: “You think I made my photographs? Freedom from myself made those photographs.”