Sometime during the ’70s, when I was in my 20s, my mother made me a quilt. Like her farmwife ancestors, she had always sewn our curtains and drapes and some of my sister’s and most of her own clothes—not of homespun wool and silk, but of permapress synthetics. Black nylon slacks, red polyester blazers, and impressive winter coats made of inexpensive polyblends. She made my quilt of the leftover scraps she stored in grocery sacks by her sewing machine: squares stitched together against a powder-blue backing, with some insulation between. I was embarrassed at first, in my rustic denim blue jeans, scruffy leather clodhoppers, and wool thriftstore sweater, at all the synthetic fabrics in the quilt. But out of sympathy for my mother with her Depression-induced frugality and out of interest in American art history, I soon came to like the bright colors. I saw symbolic value in this cross-cultural relic which melded the functional folk art aesthetics of the agrarian past and the inauthentic, mass-produced material of the present. As my appreciation for my mother’s difficult position in that intersection grew through the ’80s, so did my fondness for the quilt. The ’90s came and went, and she went with them, buried in her black slacks and red blazer, with her industriousness and practicality and her unconditional love for me. But the quilt remains intact as a warming reminder, put to good use on a bed in a summerhouse in Maine.

That’s the personal history I took with me recently to the exhibit of Molly Upton’s quilts and tapestries at the Dana Hall School in Wellesley. Without it, I’m not sure I would have made as much as I did of the seventeen pieces or so displayed in the art gallery and library. I wouldn’t have reverberated for two hours, increasingly so as those hours passed, from the initial shock of recognition at seeing, worked into this acclaimed artist’s tapestries, leftover scraps cut from bolts of the same kind of material my mother used. Who knows, in fact, but that the strips, triangles, squares, and figurative shapes of brown faux corduroy, black nylon, and lavender acrylic (admittedly mixed with a fair amount of natural fibers, including cotton, wool, and silk) that Molly Upton took pains to patch together in dozens of color-field permutations, electrifying abstract geometric quilt patterns that would be likely to induce insomnia if spread across an actual bed—who knows but that they had not been manufactured at the same textile mill in Birmingham, say, in the mid-’70s? Birmingham, Alabama, I mean, where the mills of New England long before that moved their machines. The possibility thrilled me.

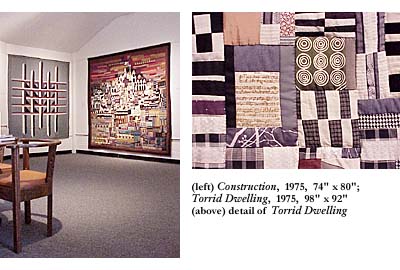

Upton’s best-known quilt, Torrid Dwelling, recently named by a coalition of crafts organizations as one of the 100 best American quilts of the 20th Century, pretty clearly evokes a view of the Greek hillside ruin she is known to have had in mind. Vertical strips of black and white cloth, reminiscent of piano keys, form an irregular skyline pattern of minarets and towers in the middle of the large tapestry. Horizontal rows of plaids, stripes, corduroys, and prints—in reds, golds, and browns—soften the upper portion of the quilt, suggesting a sunset in the background. And the foreground of the setting, the lower third of the quilt, the part you notice least and last, the part you’d put at the foot of the bed if you were lucky enough to sleep under it, with horizontal strips of brighter colors, suggests the valley of vineyards or olive groves you’d cross on your way to the hillside village. It’s an abstracted landscape reduced to rectangles of fabric that in themselves suggest nothing, just as individual brushstrokes in a stippled pointillist painting on a canvas in themselves may not suggest anything. The image is abstract, yes, and also representational. Why be too strict about these terms?

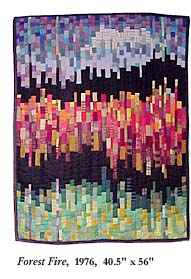

Several stunning works, mostly large quilts with geometric designs, invite and yet resist mathematical explication, pushing the viewer back toward the middle of the room to apprehend the structure, then drawing the eyes up as close as possible for a loving look at the detail. For example, there’s the relatively diminutive Forest Fire, and there’s the grand-scale Blade—both of them examples of Upton hitting her stride—or her stitch—as a visual artist, both meticulously comprised of the narrow vertical strip pieces prominent in many of the quilts: the former with three rows of them in descending order from skylike blues and lavender pastels, flamelike reds and yellows, and woodland greens untouched as yet by the forest fire; the latter with a mixed light palette in the middle flanked by strips of purple and dark blues. Alchemy, too, a quilt big enough for a king and a queen—though I hope Upton would have agreed it would be better served on the serfs in the hayloft—is worth the long look from close and far away, with that complex design of strip pieces again, twenty-five vertical lengths of them side by side in the middle of the 86″ x 79.5″ tapestry, each vertical strip consisting of two shorter discrete strips of alternating lengths in two colors not found elsewhere in the pattern, a time-consuming construction that, according to accomplished contemporary quilter Nancy Halpern, most quilters would not take the trouble to make. What results is a provocative cacophony of colors and fabric textures, edging playfully on the gaudy, exploiting the tacky possibilities of the synthetics again, not at all hesitant to make a lot of busy and joyful noise, a sound mix of the symmetrical and the unpredictable like that in the Bach organ pieces she was inspired by.

Several stunning works, mostly large quilts with geometric designs, invite and yet resist mathematical explication, pushing the viewer back toward the middle of the room to apprehend the structure, then drawing the eyes up as close as possible for a loving look at the detail. For example, there’s the relatively diminutive Forest Fire, and there’s the grand-scale Blade—both of them examples of Upton hitting her stride—or her stitch—as a visual artist, both meticulously comprised of the narrow vertical strip pieces prominent in many of the quilts: the former with three rows of them in descending order from skylike blues and lavender pastels, flamelike reds and yellows, and woodland greens untouched as yet by the forest fire; the latter with a mixed light palette in the middle flanked by strips of purple and dark blues. Alchemy, too, a quilt big enough for a king and a queen—though I hope Upton would have agreed it would be better served on the serfs in the hayloft—is worth the long look from close and far away, with that complex design of strip pieces again, twenty-five vertical lengths of them side by side in the middle of the 86″ x 79.5″ tapestry, each vertical strip consisting of two shorter discrete strips of alternating lengths in two colors not found elsewhere in the pattern, a time-consuming construction that, according to accomplished contemporary quilter Nancy Halpern, most quilters would not take the trouble to make. What results is a provocative cacophony of colors and fabric textures, edging playfully on the gaudy, exploiting the tacky possibilities of the synthetics again, not at all hesitant to make a lot of busy and joyful noise, a sound mix of the symmetrical and the unpredictable like that in the Bach organ pieces she was inspired by.

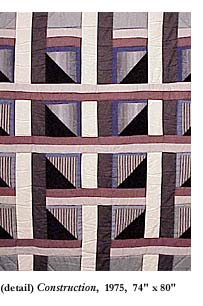

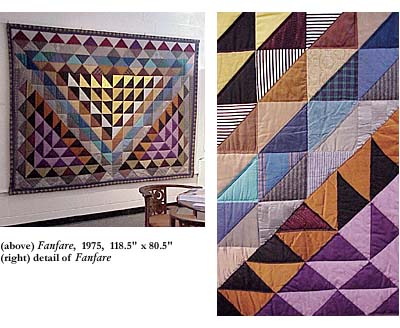

Given some rudimentary appreciation of the technical demands of quilting, the viewer finds the Molly Upton show getting better and better. Look at Construction, for example: a simple and striking arrangement of five vertical and five horizontal bars of equal length woven on one plane, like lattice strips of dough on a cherry pie, the vertical bars black on one half and white on the other, the horizontals in warm pearl and something close to ochre, the margins staggered against the greenish-gray background for musical variation. Or the enormous and lovely Fanfare: what must be a few hundred right-angled triangles, offering a range of colors in diagonal design, vibrant black and gold in the middle V-shaped image, with richly reverberating rows of blacks and whites, of blues and greens, of browns and reds, working their way toward the edge of the tapestry on the wall, the lower corners, pale and pastel by comparison, purple and lavender, green and blue—each pair again a perfect square but each individual triangle on closer inspection apparently willing to be seen with the neighboring half of the adjacent pair, so that a green triangle from a row of green-and-blue squares can go with a lavender triangle from the adjacent row of purple-and-lavender squares. As the poet Marianne Moore said, “It is a privilege to see so much confusion,” especially when you’re aware of and awed by the stabilizing mathematical and musical order underlying it all.

Given some rudimentary appreciation of the technical demands of quilting, the viewer finds the Molly Upton show getting better and better. Look at Construction, for example: a simple and striking arrangement of five vertical and five horizontal bars of equal length woven on one plane, like lattice strips of dough on a cherry pie, the vertical bars black on one half and white on the other, the horizontals in warm pearl and something close to ochre, the margins staggered against the greenish-gray background for musical variation. Or the enormous and lovely Fanfare: what must be a few hundred right-angled triangles, offering a range of colors in diagonal design, vibrant black and gold in the middle V-shaped image, with richly reverberating rows of blacks and whites, of blues and greens, of browns and reds, working their way toward the edge of the tapestry on the wall, the lower corners, pale and pastel by comparison, purple and lavender, green and blue—each pair again a perfect square but each individual triangle on closer inspection apparently willing to be seen with the neighboring half of the adjacent pair, so that a green triangle from a row of green-and-blue squares can go with a lavender triangle from the adjacent row of purple-and-lavender squares. As the poet Marianne Moore said, “It is a privilege to see so much confusion,” especially when you’re aware of and awed by the stabilizing mathematical and musical order underlying it all.

Torrid Dwelling is not the only quilted tapestry on display that incorporates figurative imagery. Midnight Gardeners, lighter fare than the other pieces in this show, offers a bright and bouncy cyclical central arrangement of white rabbits and green-leafed orange carrots, each color a discrete piece of monochromatic fabric. Two other small quilted tapestries, Caw and Caw, Caw, portray blackbirds—wild starlings, crows, or grackles I thought at first, then maybe mynas from the pet store at Woolworth—doing what black birds do best: cawing, the bird in the former perched on a swing next to a pot of flowers, and the bird in the latter looking over its shoulder and saying “CAW” in capital letters made of black stitches. In these we see the quirkier, darker side of the kind of cuddly kitten imagery we might expect to emerge from a modern-day quilting club still reliant on the traditional stock of American folk-art images and their corresponding sentiments—a club that the viewer may suspect survives to this day, say, in the exclusive neighborhoods surrounding the Dana Hall School in suburban Wellesley.

Even if Molly Upton had quilted exclusively in nonrepresentational abstract designs, that wouldn’t have made her some sort of far-out experimentalist. Nineteenth Century New England and Appalachian women at hearthside and treeshaded quilting bees modified earlier Puritan-era designs with their own abstract representations. The names they gave the patterns—Star of Bethlehem, Courthouse Steps, Jacob’s Ladder—invited the eye to make something whole of the individual squares, rectangles, and spheres they’d stitched together. They worked with symmetrical patterns made of paired right-angle triangles of different colors, like those we see in Pine Winter and Summer Pine, which, according to Nancy Halpern, are the only two quilts in the show that actually follow traditional patterns: six triangular shapes stacked vertically one on top of the other in each to suggest the pine, black and white fabrics dominating the winter pine, greens and golds the summer pine—with a compass star crowning both trees in bold and conspicuous homage to the origins of this craft.

The quilt my mother made me got me into the mood of the Molly Upton show. What carried me through it in the long run was the opportunity to see how the quilts make art of craft, supporting the claim that Upton was a painter who worked in cloth. My experience could not help but be enhanced, however—like a vitamin supplementing a feast for the eyes—by the story of Molly Upton herself, available for public viewing in news clippings on the wall and in notebooks on the table. I’d already read on a postcard announcing the opening of the show that she was born the same year I was, 1953, and that she died at 23, in 1977. From the clippings and notebooks in the gallery I learned that she graduated from Dana Hall in 1971, probably the same week I graduated from public high school, and that she went to college at Macalester and UNH, but quit before graduating to indulge her newfound passion for quilting with a friend in their studio in Cambridge, where I have lived for many years now. She went to San Francisco, according to my calculations, just a couple months after I first surfaced from the subway into Central Square and fell in love with the international human mosaic—or quilted human tapestry, maybe—that I saw in the streets. I had a geographical and generational bond with her there, and I felt a certain nostalgic attraction to the pictures of her in the gallery—a slender and attractive young woman, apparently of some countercultural inclinations, intensely concentrating on her stitching in one photo, stretching out languidly on one of her quilts in another. In no picture I saw there, and in no quilt either, could I detect, and you can bet I tried, the terrible trouble or possessive biochemical demons that in 1977 made her put down her needle and thread, that grabbed away and set aside the lively handworked pieces I saw in this show, and that walked her out onto the Golden Gate Bridge for the plunge to her death in the water below.

It’s nice that Molly Upton managed to design and stitch together as many as two dozen quilts and tapestries before her death—one of which, Watchtower, is on display with Nancy Halpern’s Archipelago and others at the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell through late March—and it’s unfortunate she couldn’t stay around to make more.