In popular lore, the narrative of the aging painter often tilts tragic—Monet went blind, Rembrandt and Van Gogh died in penniless anonymity, Goya succumbed to dementia in exile, and Vermeer left his family in massive debt. Then there are the scads of names we don’t remember, the peripheral footnotes in yellowed art history books. The slow choke of time shows little kindness to the creative. Rapid trend turnover and increasingly shaky hands leave many painters gasping in the wake of obscurity, a fate that tends to strip late work of that pressing vitality necessary for relevance. So what of the career iconoclast? An artist whose tireless thirst for process far outpaced his patience for fame? The current exhibition at Adelson Galleries Boston grapples with these questions in the case of Jules Olitski (1922-2007), legendary abstractionist, painter’s painter, and veritable bastion of uncooperative modernism. Titled Jules Olitski in the 21st Century, on view through December 22nd, it features an array of 24 pieces created in the twilight of the artist’s life, the majority of which have only recently been made available by FreedmanArt in New York City, the artist’s estate managers, for public viewing. The collection provides a refreshing peek into the psychology of a man whose artistic passion outlived him in dazzling strides, crafting painted paeans to invention in the face of mortality.

The surname Olitski has long lived in comfortable proximity to words like “genius”, “visionary”, and “innovator”. And for good reason—his emergent work in Color Field painting established him as the leader of a new aesthetic generation, grouping him with heavy-hitting contemporaries like Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, and Anthony Caro. Following a large French & Company solo exhibition in 1959 under the auspices of art world juggernaut Clement Greenberg, Olitski developed his signature spray-gun technique of staining raw canvas with atmospheric mists of thin, vibrant dyes. Accepting the influence of Kenneth Noland’s “target” paintings, Olitski began to experiment with the concentricity of brightly colored elliptical silhouettes, creating expansive, precarious compositions that combined the titanic reverb of Mark Rothko with the mischievous optical winks Wassily Kadinsky made famous. Still, the sterile geometry favored by his peers clashed with his investment in tangible surface, inspiring Olitski to forgo water-soluble washes for meatier fare as the nineteen-sixties drew to a close. He returned to the matter-based painting style he had championed during his stint at Beaux Arts Institute with a newfound sophistication, introducing a Jean Dubuffet-inspired savagery to the world of his artworks. It’s worth noting that the Color Field paintings responsible for Olitski’s renown comprised only a small portion of his oeuvre. While his catalog may be contiguous in development, the spray pieces look more like anomalies than standards to a twenty-first century eye.

The nineteen-seventies and eighties bore witness to Olitski’s attempts with hand-mitts, mirrored Plexiglas, brooms, rollers—whatever instrument lay wantingly in his studio that evening, really. He continued to spotlight surface by varying the opacity and transparency of acrylic paint, utilizing the scumbling, impasto, and glazing techniques of the old Renaissance masters he so fervently admired. Then there were minimalist sculptures, the grey and white expressionist murals, the small nineties landscapes, the spackle pieces, the nude studies, and, naturally, the orb paintings, a wide selection of which are on display in the current exhibition.

Jules Olitski’s disinterest in aesthetic consistency has long been a subject of frustration for art historians and dealers alike—his retrospectives do have a tendency to look like group exhibits—but that alleged lack of career cohesion does little to undercut his artistic influence. The man’s technical command of his medium was nothing short of magical—a power that, accompanied by his gift for creating atmospheric gradiation in middle-value shade ranges, distinguished him as an unusually emotive colorist. He re-imagined the most evocative compositional innovations Abstract Expressionism had to offer as purely painterly, drawing atmosphere from emptiness and balance from gesture with a suave, dramatic hand. Olitski’s greatest gift, however, might have been his ability to achieve sophisticated contrast without sacrificing spontaneity—even a casual viewer can’t ignore the adolescent playfulness with which he approached paint application. The tension he posited between linear margin and chromatic space still vibrates at a reckless pace, dissolving mere mark into shimmer-scapes of surprisingly immediate carnality. An indomitable sense of fun sears through the pathos of his tonal dialogues, affording the best pieces an unstoppably frenetic, rhythmic quality.

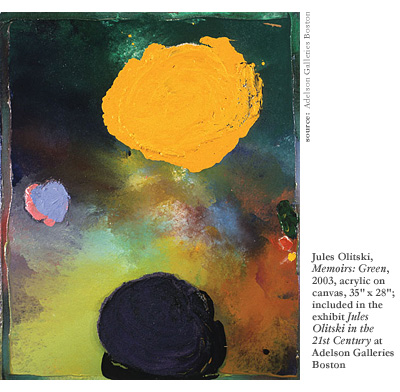

And then there’s the framing. This technique emerged for him in the nineteen-seventies, but, as evidenced in some of the current exhibit’s louder moments, proved fruitful for Olitski well towards the end of his life. Linear panes bordering otherwise resolved images serve to center the whole and underscore their material objectivity. Such an illusionistic procedure might initially seem self-parodying given his oeuvre, but it’s important to remember that he remained, above all, a dedicated formalist. His was not an art of conceit, but of result. He believed in beauty. As such, the orb paintings present a quandary for Olitski acolytes. Given the artist’s lung cancer diagnosis in 1997, their existence alone represents an incredible achievement, a true triumph of the human spirit. There’s little precedent for this sharp turn—instead of dedicating his final years to a filtered exploration of career essentials, Olitski tried something totally new, a move complete with all the missteps and failures expected of such an investigation. Some pieces, like the symphonic Memoirs: Green, boast nuanced interpolations of late-era Hans Hofmann. Others, like the staid and muddy Night Vision: January Tenth, only manage to combine the least exciting aspects of the New New Painters with an Arthur Dove distaste for suggested perspective. For an artist so enamored with the purity of inspiration, the orbs can seemed willed, even forced, creating a strain in Olitski’s otherwise graceful lexicon.

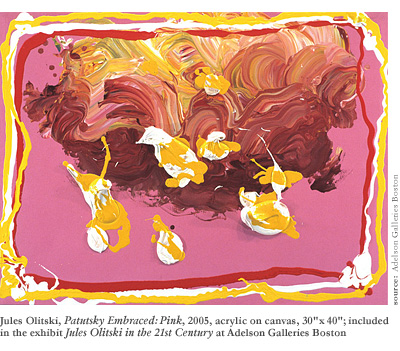

Still, the orbs dispense with the impassive irony of eras past. These paintings aren’t about re-inscription or genre progression; they are simply trying to talk to us. Olitski may have described them as “celebrations”, but they impact the space with the propinquity of voice mail, striving desperately to commit rupture in the viewer’s experience. Such earnestness, while invigorating, proves occasionally clumsy in execution. The larger acrylics struggle to achieve the frothy modulation of surface Olitski typically masters, and his reliance on molding paste often robs the canvases of the their usual fluidity, leaving the majority congested and static. Patutsky Embraced: Pink, for instance, occupies the wall with the hollow extravagance of an MFA thesis finale, an optical interrobang that won’t chance failure in seduction. Olitski has brandished a brush loaded with warm browns over a slick, Pepto-Bismol basecoat, forming a slow-descending centric swarm of unhinged, muddy gesture. A smattering of expressionistic white and yellow islands interrupts the top-heavy composition, providing a much-needed reprieve from its background sting. The three wriggling frames—one white, one yellow, one crimson—swirl together in anxious, plastic concord at the painting’s outer corners. Indeed, no one could accuse Olitski of shirking the stretches of his medium. His obvious revelry in acrylic manifests throughout this exhibit, but this painting’s specific brand of joy is by far the most manic—the smaller paintings flanking this work seem stationary in comparison. Its olive-toned counterpart, Patusky Embraced: Green and Yellow, shouts just as loud, but thankfully in a richer bass. The heavily encrusted surface restores a bite to the painting’s form of address, employing velvety background depth to justify the central mass.

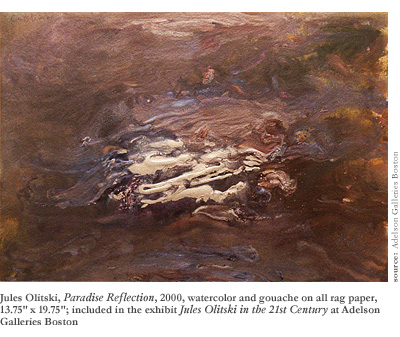

The orbs tome in harmony with their planetary contexts, but it’s the watercolors on rag paper that really sing. Paradise Reflection, a modest study sequestered in the gallery’s downstairs anteroom, shimmers and lurches across its foundation with a delightfully irksome, animal insistence absent from its main room neighbors. Using gouache as a structural centerpiece, Olitski wrought a textural dynamism so delicate and mouth-watering it almost seems organic to the page itself. He attains an effortless chiarascuro by grounding silver-toned lavender highlights with resonant umber swaths, and to truly hypnotic effect; he has finally landscaped tactile abstraction. The equally diminutive October Dream-Gold also succeeds where the acrylics could not. While it echoes the compositional tenets of its more ambitious upstairs cohabitants, the absorbency of the paper lends this piece a gorgeous, dreamy softness, standing in direct opposition to the cloying hysteria of the Patusky paintings. It’s perfectly possible that Olitski’s advanced age and failing health contributed to this dichotomy. Medium-soaked acrylic requires quite a bit of arm strength to manipulate properly, and perhaps his fascination with circular globules stemmed partially from physical convenience, a completely understandable modification. Assumptions aside, the smaller watercolors remain the most worthwhile pieces in attendance, largely by virtue of their comparative timelessness. Works like Paradise Reflection don’t date themselves with the same material aggression as the acrylics, the latter of which regularly function as studies in a newly available formula rather than fully realized narratives.

Of course, any conversation on the topic of Olitski’s relevance leads us back to the exhibit’s stated intention—to determine his position in twenty-first century art dialogue. A discussion was organized at the gallery, aptly named “The Late Works of Jules Olitski: A Panel Discussion”, which convened on the afternoon of October 26th in explicit service of this objective. The artist’s daughter, Lauren Olitski Poster, and grandson, Harry Poster, fielded questions like, “Did the artist listen to music while he painted?” and “Would you feel comfortable sharing some precious childhood memories of Jules?” from gallery director Adam Adelson and various chatty audience members. Minutes beforehand, friends of the Olitskis, friends of the Adelsons, and a few devoted free wine enthusiasts looked on as the short 2011 documentary Jules Olitski: Modern Master, directed and produced by Andy Reichsman and Kate Purdie, played for twenty minutes to scattered applause. The film informed us that Olitski worked almost exclusively under cover of darkness, and that no one, no matter how close, constant, or culturally relevant, bore witness to the sacred alchemy of his painting practice. According to those interviewed in the film, he made no distinctions between figurative and abstract painting, had little time for conceptual reference, and considered himself an artistic vessel for an unknowable Judeo-Christian entity, slave to his medium and specially subject to divine inspiration. Footage of the artist in conversation portrays a twinkly-eyed pontificator brimming with all the expected amounts of gusto and free advice. He widens his eyes. He raves about Rembrandt. He gesticulates with a cigar as he expounds upon the role of intuition in his process. He laughs at his own jokes.

Strangely, the entire event smacked of the funerary in its approach, an odd if ultimately inevitable outcome for an exercise that professed to update Olitski’s cultural significance. While his unconventional techniques were inventoried at length, the orbs themselves were not discussed, perhaps out of deference to his legacy—they’re important, but none are masterpieces—or, more cynically, in an attempt to sell paintings (priced as high as $48,000) that require more than a little bit of contextual defense. Much was made about re-introducing Olitski to a Boston audience, since most consider his 1973 blockbuster Museum of Fine Arts, Boston retrospective a career highlight. But given his obvious boredom with the mainstream trappings of artistic accomplishment, this endeavor seems extraneous to his memory.

So what place does Olitski occupy in a contemporary canon, then? That question might be a non-starter, after all. Even as a hot young talent, he stuck to his traditionalist roots, always much more concerned with the satisfaction gained through making than the conceptual yards claimed through movement-based progress. In an interview conducted the same year he received his cancer diagnosis, Olitski told William Ganis, “I have never felt bound by any art theory. I just try to get into the work and let it in some intense way be made.” Such a statement typifies his attitude toward externalized frameworks for cultural consequence. He was inspired by his contemporaries, sure, but what really mattered was the life of the work, not some self-conscious commitment to advancing the avant garde. Jules Olitski’s paintings are designed to be moving, and as any Pixar buff could easily testify, what stirs our hearts does not always have to blow our minds. His investment in classical elegance may grate against the relentless pretension of today’s market, but even if Olitski could fit in, he wouldn’t want to. These orbs are elemental screams into darkness, exuberant, lonely even, but never devastated by circumstance. It is our duty to receive these transmissions as final howls, not last words.