Four centuries later, it seems difficult to think of an epic poet as an unlikable fellow. Yet John Milton (1608-1674)—the blind, regicidal Puritan who spent his free time with heroic couplets—was not one to make friends. A king put a price on his head, publishers refused to attach his name to his works, and—perhaps most insultingly—a latter-day reader of Paradise Lost mustachioed his likeness. These historical morsels are often lost in the canonization process, through which the personalities and identities of deceased authors are mostly synthesized with their works. So it is perhaps with these oversights in mind that The Morgan Library & Museum in New York City—the public home of J. P. Morgan’s library and antiquities collection—presents John Milton’s Paradise Lost, a new exhibition on view through January 4th, 2009 that looks to the private lives of books and manuscripts for the forgotten history of John Milton and his poetry, marking the 400th anniversary of his birth.

Installed in the Morgan’s modest Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery—a square room perhaps twenty feet on a side—the exhibition comprises five small vitrines and a half-dozen hung paintings and engravings. The visitor’s attention is focused squarely on the codex, with well-selected supplementary works garnishing the collection of first editions and unbound manuscript pages. There is elegance to the simple design that seems in keeping with the privacy of library experience and the sedentary reading of poetry, but the exhibition’s unambitious structure is neither insightful to Milton’s modern admirers, nor welcoming to new audiences that are unfamiliar with his work.

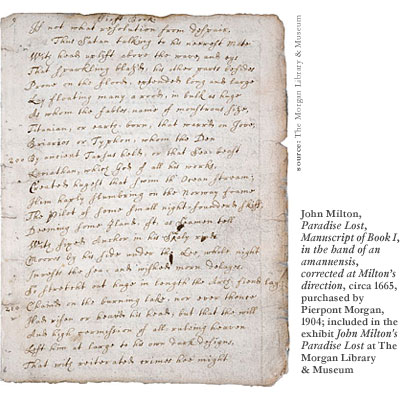

Smallness is at once the exhibition’s central virtue and its frustration. Four leaflets (totaling eight pages of script) from the only known Paradise Lost manuscript (which was unbound for restoration and display) stand at the exhibit’s center, and their hand-wrought aesthetics are singularly compelling. This, however, is strangely complicated by Milton’s personal history and the history of the volume’s publication. Blind at this point in his life, Milton composed Paradise Lost nightly by committing twenty-line segments to memory, dictating them each morning to family members or paid acquaintances, known as amanuenses. These associates would then help arbitrate his editing process, reading back the transcriptions as he specified amendments to the new work. Their collected recordings were then passed to a professional scribe, who compiled the manuscript, which was originally used to typeset the poem’s first edition (following Milton’s final revisions, which are also visible on the codex).

So, unlike other presentations of historic manuscripts that claim to capture “the poet’s hand,” these pages exhibit considerable distance between Milton himself and their specific, physical creation. This is, however, more a point of meditation than a distraction, and it offers the curators an important entryway for a discussion of Milton’s personal history and writerly process.

Given the weight of its relics, the exhibition can be considered an unofficial flagship of the broader celebration surrounding Milton’s tetracentennial anniversary. Concurrently, institutions ranging from the New York Public Library and the Williamsburg Art & Historical Center in Brooklyn to Christ’s College, University of Cambridge in England (Milton’s alma mater) are mounting examinations of his life and works. In particular, the complementary biopic investigations have revived interest in the poet’s biography, which the Morgan successfully constructs through skeletal gestures towards Milton’s involvement in politics and public life, which largely trumped poetry for most of his lifetime.

While at Christ’s College, Milton undertook a seminary education that would have led him into the Anglican priesthood, had he not remained through 1632 to complete a Master of Arts degree. Poetics took precedence among his interests and—following graduation—Milton spent six years completing a rigorous, self-directed course of poetic study in which he mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, and Old English.

His trajectory, however, was redirected following the civil strife in England that led to the Glorious Revolution and Oliver Cromwell’s eventual ascension to the position of Lord Protector. Milton—who had aligned himself with Puritan Protestantism and the English Parliament through a series of political treatises attacking the Church of England, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the monarchy of King Charles I itself—was named the Secretary of Foreign Tongues to Cromwell’s Republic in 1649, an office that required him both to negotiate with foreign diplomats as a secretary of state and to disseminate propaganda descrying the former king. All of this, of course, changed radically following the Restoration, and King Charles II’s orders for Milton’s arrest and the burning-by-the-hangman of all his published volumes in 1660.

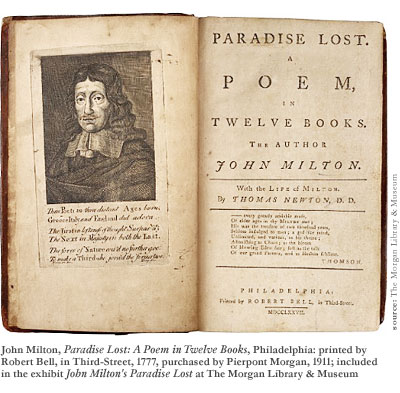

One of the great feats accomplished by the Morgan’s curatorship here is the reflexive telling of this story by highlighting features unique to specific editions of the text that chart Milton’s personal progress. The first edition, for example, which was printed by Peter Parker in 1668, attributes the poem to “J.M.,” for fear that Milton’s incendiary political reputation would mar sales or result in a boycott of the work.

Similarly, the works published during Cromwell’s Republic lack the distinctive imprimatur found on all earlier or later volumes in the collection, reflecting Cromwell’s temporary repeal of the Licensing Act (reinstated by Charles II in 1662), which required that printers and publishers acquire specific licenses to legally print or distribute any book. The imprimatur itself—named for the Latin expression “let it be printed”—signified that authorization had been granted by the Stationers’ Company and asserted the publishers’ safe right to print the book.

The Paradise Lost manuscript is peculiar in that it carries its own imprimatur—typically, manuscripts were recycled or discarded, but the imprimatur suggests that in this case it was something of a professional insurance policy for the publisher, who likely feared retribution from the restored monarchy. This not only underscores the ubiquitous fear and controversy surrounding the publication of any of Milton’s works, but also gives a hint as to why this manuscript alone survives.

Charmingly, a single volume of Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books (the first American edition published in 1777) bears on its frontispiece engraving of Milton’s portrait an ink mustache, the indelible graffito of some mischievous former owner. The gesture is a touching bit of humanism in and of itself, and that the Morgan’s curators call attention to it in the volume’s placard further underscores their interest in grounding this exhibition in the physical history of objects.

Museums often make a poor habit of imparting timelessness to artifacts, encouraging visitors to imagine that such objects have been removed from social circulation and preserved perpetually since their creation. John Milton’s Paradise Lost enjoys the small triumph of an atmosphere in which viewers encounter the personal, time-rooted history of old books. As the public arbiters of a private, personally acquired collection, the Morgan is perhaps more attuned to such a subtle curatorial concern than other institutions, and it is perhaps the strongest and most sensitively deployed thread unifying this modest exhibition.

Selected with similar scrupulousness, the eight manuscript pages lying at the exhibition’s center encompass well-regarded verses from across the book, including the opening incantation in which Milton aligns himself with Virgil and Homer, invoking a “heavenly muse” to help him “justify the ways of God to men” through “things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.” Another selection found on the manuscript pages connects Milton’s fascination with Satan—his chief protagonist—to Galileo, one of Milton’s most admired peers, who he had visited in prison in Florence in 1638. Satan’s “ponderous shield” is aligned with “the moon, whose orb / Through optic glass the Tuscan artist views” in a gripping celestial metaphor and the poem’s solitary allusion to a contemporary figure.

Peripheral to the manuscript and the early editions of the published poem, several works of visual art complete the exhibition with interpretations that were produced during the poem’s historical moment. Here, the intimate smallness feels more limiting than focusing, as the exhibition occupies the uncomfortable position of a visual display centered on a literary work.

As museums and the visual media they present operate in a far more limited timeframe than literary works (in less than thirty seconds you walk by paintings or vitrines; you sit down to read a book perhaps for hours), the supplementary works accompanying the manuscript intend to provide visitors access to the unfamiliar narrative and the landscape of its themes and imagery. The scant collection does successfully construct the poem’s central figures, but the detail is too poorly resolved for Paradise Lost newcomers—a single Richard Westall painting characterizes the spirit and aesthetics of Milton’s heroic Satan perfectly, yet without literary familiarity or a broader secondary context, this will be lost on most visitors.

One small William Blake illustration, depicting the poet inspired by his “heavenly muse,” is the only contribution from Milton’s most significant contemporary, and though the miniature work is rich and moving in spite of its size, Blake’s fully illuminated edition of Paradise Lost is absent and sorely missed.

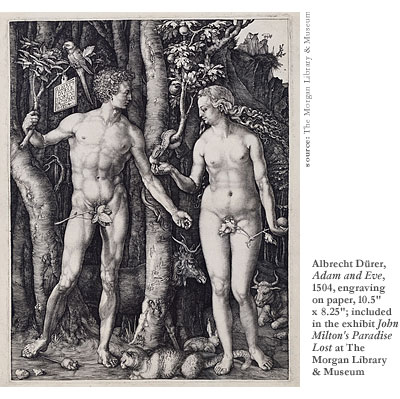

A black-and-white Albrecht Dürer engraving transmits an analogous sense of disappointment that seems to linger throughout the small exhibit. The work itself—which depicts the pre-lapsian couple, apples in hand—is a compelling masterpiece and an achievement of both fine artisanship and the visual transmission of narrative, but the richness of its careful detailing is lost without a thorough explication, which the museum fails to provide. As with Blake, the engraving is not Dürer’s only meditation on Paradise Lost, and the exhibition suffers for not employing their works as an initiating portal for unfamiliar visitors, or an educating plunge into the poem’s symbolism for the indoctrinated.

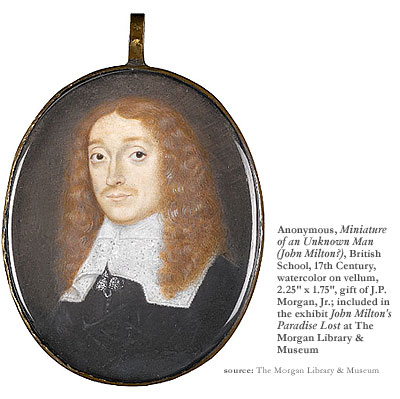

The most curious piece of art accompanying the manuscript is a small portrait in watercolor on vellum. The unambiguous title, Miniature of an Unknown Man (John Milton?), seems another stitch of curatorial cleverness, and when you take it together with its mustachioed neighbor and the paucity of visual works in the exhibition, we are reminded that, in the spirit of the Morgan Library’s history and mission, this exhibition is specifically invested in the physical history of an object.

This means, disappointingly, that it is not an exhibition about a poem, a poet, or his poetry, which assuredly maintain more modern interest in Milton than the nuances of book history and art ownership. It is, perhaps, less a celebration of John Milton’s poetry than of J.P. Morgan’s possession. But in either case, the exhibition—in all its smallness—succeeds within the boundaries it has defined for itself.