In late 2005, BBC journalist Mark Kermode interviewed German film director Werner Herzog near Herzog’s Los Angeles home. The interview, which took place outside, was interrupted by an attack from an unseen assailant wielding an air rifle. Herzog, despite being struck in the abdomen, insisted that the interview continue, although he did yield to relocating indoors. According to Kermode, the director’s response to the incident was this: “It was not a significant bullet. I am not afraid.”

This anecdote, which quickly passed into film legend, is a perfect means of introducing the uninitiated to the vital qualities of Herzog as both a man and director. Since making his first shorts in Germany in the early 1960s, Herzog has released dozens of films. While his strong stylistic choices and independent productions have curtailed any mainstream success, he is numbered among the great filmmakers of the late 20th Century by professionals and aficionados alike.

Herzog has cultivated a reputation for a fearless, obsessive approach to filmmaking. He creates most of his films on location, frequently in inhospitable wilderness, and bases many on actual events, rendering them as fiction and documentary in almost equal measure. Indeed, those labels often become nominal when considering his work. More so than perhaps any other director of his generation, Herzog blurs the lines between historicity and fantasy. He surrounds his “fictional” works with the veneer of fact, yet at the same time takes extensive liberties in the pursuit of truth—to Herzog, fact and truth are two discrete concepts. Despite drawing inspiration from history, Herzog does not hew to a strict reconstructive approach. He weaves allegory out of reality and imagination, boiling the incidents of the past down to what he sees as their most essential and compelling elements. On a technical level, Herzog’s goal is to give his audiences as unimpeded and unfiltered an experience as possible. He casts unknowns, uses very little in the way of artificial lighting, and lingers on shots, creating a documentary feeling to increase the implicit “truth” of his films.

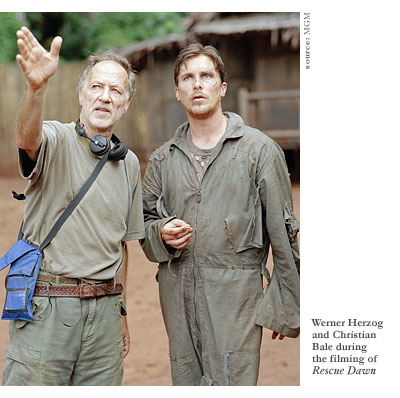

Rescue Dawn (2007), Herzog’s newest film, is on some levels a departure from these characteristics. While still very recognizable as his work, the faintest traces of a Hollywood sensibility make their presence felt. The American characters are all well-known Hollywood actors, and the ostensible subject matter—the travails of POWs during the Vietnam conflict—is intrinsically American as well. Despite these paeans to commercial appeal, however, Herzog maintains his artistic integrity, and the resulting hybridization of approaches is as harrowing as it is beautiful.

The film concerns German-born Navy fighter pilot Dieter Dengler (Christian Bale), who is shot down over Laos in 1965 prior to the United States’ official involvement in Vietnam. Taken prisoner, Dieter plots an escape with fellow POWs Duane Martin (Steve Zahn) and Gene DeBruin (Jeremy Davies). The capture, escape, and subsequent events form the tapestry that supports Herzog’s journey into the world of a man driven to extremity by circumstance.

One of the more intriguing ways to examine Rescue Dawn and its place in the Herzog canon is to draw parallels with the director’s other film most similar in premise and ambience—Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes (Aguirre, the Wrath of God) (1972). Doing so immediately throws the newer film into sharp relief. The superficial differences serve to distract the casual viewer from deeper thematic shifts. Rescue Dawn is not a departure for Herzog, but the product of an evolution in narrative concerns.

Both films, broadly, display the descent of Western man into untamed and hostile wilderness. The titular protagonist of Aguirre is a mutinous 16th Century conquistador played by the volatile Klaus Kinski, an early collaborator of Herzog’s, who commandeers a detachment of soldiers and slaves in South America to find the fabled city of El Dorado. Dieter and Aguirre are both military men confronted by a disordered natural realm of which they are entirely ignorant. The key difference, however, is that while Aguirre attempts to impose his own manias on the wilderness and is destroyed for it, Dieter finds a new equilibrium with the larger world once the trappings of civilization are stripped away.

The final scene of Aguirre, one of the most famous in Herzog’s entire filmography, helps to typify this distinction. Most of the expedition, including Aguirre’s daughter, are dead or dying from starvation and disease. Only Aguirre remains on his feet, undaunted and quite mad, as the party’s raft drifts downriver. A troop of monkeys descends on the raft, running rampant over the bodies and detritus. Aguirre rants and raves at them, vowing to marry his daughter and found a pure dynasty that will rule the continent. The camera planes over the river, spiraling in tighter and tighter on Aguirre, as he stands alone among the monkeys with dreams of conquest and power still written across his face.

Herzog’s version of the story of Don Lope de Aguirre stands as a compelling indictment of unchecked ambition and an affirmation of man’s powerlessness against nature. This is a concern that appears again and again in Herzog’s work over the subsequent decades. In recent years, however, both Herzog and his protagonists seem to have arrived at a more tranquil endgame. In Rescue Dawn, the character most like Aguirre is not Dieter, but supporting player Gene. Obsessed with the smells of old processed food wrappers and convinced that release is imminent, Gene is unable to forgo his misguided perspective and is abandoned by the more enlightened Dieter following their escape. Gene vanishes into the jungle, never to be seen again. One can assume that, much like Aguirre, he meets a bad end.

But Herzog is no longer interested in bad ends. Dieter suffers, even more so than Aguirre, but his tribulations uplift him rather than destroy him. In a scene parallel in both placement within the film and overall significance to the finale of Aguirre, Duane is brutally murdered. Dieter does not panic or lash out—he flees, into the jungle, merging with the landscape and evading his pursuers. There is a shot where the murderers race past Dieter, who stares out at them, only his eyes visible through the leaves, his body perfectly still. This is perhaps the most important image in the entire film. It demonstrates that Dieter has learned the lessons that Aguirre and Gene are incapable of absorbing. His advice to the crew of his aircraft carrier following his rescue speaks to this: “Empty what is full…fill what is empty.” By disposing of those parts of himself that are useless and changing to accommodate what he learns, Dieter is his own salvation.

Likewise, it is clear that Werner Herzog has learned a great deal over his four-decade career. His early works, fraught with tensions over his collaborations with Kinski and lack of funding, are grimmer and more brutal. As indicated by Rescue Dawn, however, a new Herzog has begun to emerge—more optimistic, perhaps, and certainly more sure of himself, as he nears seventy with no signs of slowing down. Some things, however, have not changed—Herzog’s artistic patience, his dedication to the ecstasy of truth, and his willingness to unleash some significant bullets of his own into the world of cinema.