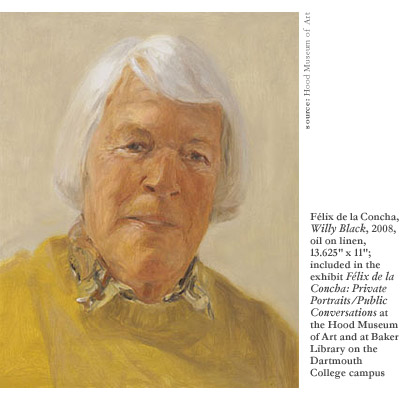

Willy Black stares at us from the canvas on the wall. The portrait shows an older woman with white hair. She has a soft smile beneath tired eyes and her face is well-wrinkled. Her mouth is frozen in a half-smile, the brushstroke shine on her lips leaves the impression that the painter captured her image in the middle of speaking. A quote from her on the wall reads, “We’ve taken all the places kids can learn limits away from them and set them for them, and I don’t think that’s right. I think that a kid has to learn to experiment to learn what their own limits are and they can’t just be imposed on them all the time. We’ve taken a lot of childhood away from kids by all the changes we’ve made on everything they do.”

A woman and her daughter walk past, and the mother stops in front of the portrait. “Willy Black,” she says, reading the placard next to the painting. “I knew a Willy Black. She was my kindergarten teacher.”

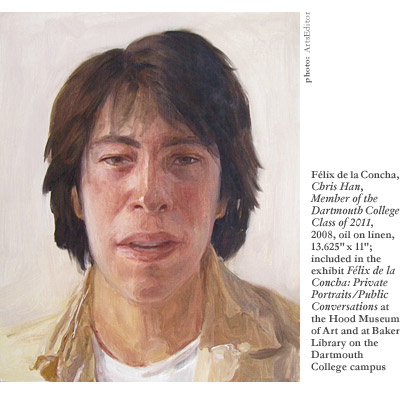

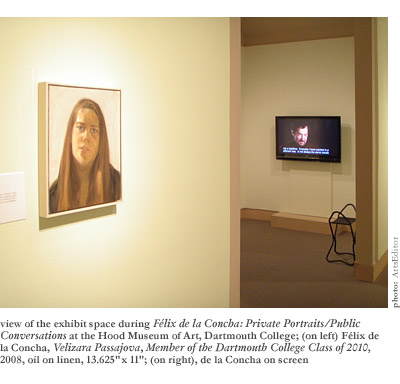

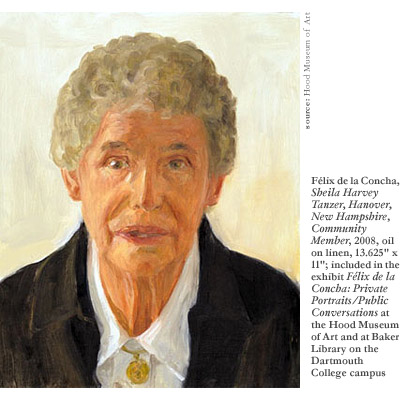

This portrait is one of fifty-one on display in the exhibit Félix de la Concha: Private Portraits/Public Conversations at the Hood Museum of Art and at Baker Library on the Dartmouth College campus from April 4th through September 27th, 2009. The exhibit was undertaken in conjunction with the Dartmouth Centers Forum (DCF), an organization seeking to create dialogue on a variety of social, political, and intellectual topics. The Hood commissioned artist Félix de la Concha to paint portraits of people from the local community, focusing on the DCF’s campus theme for 2008-2010, “Conflict and Reconciliation.”

Diverse members of the Dartmouth College community and surrounding upper Connecticut River valley sat for the portraits. Included in the exhibit are the now former president of Dartmouth, the student body president, and members like Willy Black, who apparently had no direct connection to the college until this exhibit. Each portrait was painted in a two-hour session, in which de la Concha listened to the sitter speak about areas of conflict and reconciliation in their lives. In addition, he recorded video and audio of each session, portions of which are included in the exhibit.

De la Concha was trained in the Spanish tradition of painting. He theorizes that it is a natural tendency for Spanish children to gravitate toward painting, perhaps because of the image-based Catholic roots of the culture. There is an endless list of famous Spaniards—Pablo Picasso and Diego Velázquez, to name a couple of de la Concha’s childhood idols. As no one else in his family is a painter, he guesses that maybe he was meant to fill that gap. Previous projects of his include One a Day: 365 Views of the Cathedral of Learning, which consisted of 365 paintings—one a day for a year—of different views of the Saint Paul Cathedral from points in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Another, Fallingwater en Perspectiva, is a number of paintings of the Frank Lloyd Wright house Fallingwater.

and Dartmouth College student, class of 2009

How he began the very specific act of portraiture with conversation, de la Concha says, “My first project I did about four years ago of ‘portraits with conversations’ was for purely artistic reasons. The theme was to talk about painting itself, and as an experiment to see what kind of work would emerge while I would be talking to the sitter and painting them, therefore disjointed in my concentration. I had in mind the automatic drawings from the Surrealist movement. And I had as sitters people from different fields in the cultural world. From that project, aside from the aesthetic results of the paintings, I realized that the testimonies I was recording were very special, because of the special circumstances in which they were recorded.”

De la Concha finds that the conversations affect the process a great deal, almost more than he would wish, as a painter. “Not just because the sitters are talking, and therefore moving all the time,” he says, “but because I feel completely naked. A portrait is a very delicate work. Any brush stroke can change it radically and I cannot have conscious control of it. The sitters may consider they are doing their confessions, but I am revealing my inner soul there, too. And what they are telling me, and how they express themselves, and how they pose, of course everything affects the result.”

The most vulnerable part of the process for him is the very end, when he has to show the sitter the portrait, the culmination of two hours of work affected by everything said. Sometimes it comes out well, and sometimes not. Sometimes the sitter is happy with the image, sometimes not. For example, at a lunchtime panel on May 5th, three students who participated in the project (Molly Bode, Andrew Zabel, and Micaela Klein) were asked what each thought about their resulting portrait. All agreed that a “sustained period of reconciliation” was a good way to describe their first reaction.

The work could end there, with the completed portrait. The exhibit would be emotionally empty if this were the case. In the paintings, de la Concha has placed no overt symbols of the conversations. These are simply paintings of people. They almost seem to remove individuality from the sitters. The lighting is all the same, the colors are all a similar muted palette, aside from the occasional bright red in a shirt or tie. All the sitters look artificially close in age. There are subtle shifts in body language and in facial expressions, but all the portraits are remarkably similar despite the diversity of the subjects. The only things that set them apart are small placards, like the one next to Willy Black, displaying the person’s place in the community and a single quote pulled from the entire two-hour portrait session.

But this is not a dead exhibit of homogenous portraits. De la Concha filmed and recorded audio of each session as it took place. Then he edited the recordings, cut them up, and re-arranged them to create a multimedia presentation. This combination of video, audio, and paint adds crucial depth to the exhibit—beyond a simple study in faces toward something deeper with long-reaching social implications, toward a work of art rather than a piece of craft, a work that is almost an academic study of one community’s diverse views on conflict and reconciliation.

The very first thing a viewer of the exhibition sees is an LCD screen split four ways. In each quadrant, to illustrate the process, de la Concha has placed a two-minute video of the two-hour process, compressed. In fast-forward, a sitter talks while de la Concha paints the portrait. He starts with rough outlines of tone, the light and dark, then slowly refines the splotches into the shape of faces. As they talk, the speakers run the gamut of emotions—smiles, frowns, skin creased, eyebrows raised. They shift, straighten, and slouch, and all the while the portrait is refined. The brush darts around the four faces simultaneously, filling in the eyes and mouth. Grimacing lips transform into a slight smile. De la Concha has freed his oil paintings from the constraints of time—no longer are they bound by the canvas. In these videos, they are fluid and expressive.

and Dartmouth College student, class of 2010

Deeper in the exhibit are more screens, with different presentations of the portrait sessions with de la Concha, to different effects. There is a screen continually displaying entire two-hour sessions. Put on the headphones and you are transported into the studio with the artist and his subject. You can listen to the one session for as long as you wish as the portrait-sitter talks through moments of conflict and reconciliation, and gives generalizations on the world through his or her own eyes. In real-time, the portrait takes form, and you can see de la Concha’s brushwork, his selection of colors, and deft technique.

On one screen in the back, clips from each of the sitters’ portrait sessions are cut together to create a single continuous monologue. It is a jumble of thoughts, but the juxtaposition is striking. Diverse individuals continue conversations started independently, yet the thinking is similar, hinting at a common outlook within this community.

The exhibition is a bold effort that leaves the viewer feeling raw, laid open through the display of so many personal lives. This personal connection is its great strength. Rather than approaching the daunting, complicated topics of conflict and reconciliation from the front, the exhibit takes a more circuitous approach to the subject. The exhibit itself puts forth no doctrine. Instead, the accrual of so many personal connections over time begins to form a picture of the community.

Sheila Harvey Tanzer, a resident of the community, says, “The older I grow the more I believe that it’s our perceptions of a certain situation that are the most important factor… How do we perceive it? And what can we learn from it? Those seem to be ways to keep the mind on something creative and positive, rather than falling into the trap of anything negative.”

The images in Félix de la Concha: Private Portraits/Public Conversations are deep and complex, multifaceted representations of the subjects. Each portrait is a unique collection of video, audio, and paint. While none of the portraits are truly exemplary works of art, they don’t need to be. The exploration within multiple media creates a new place for the old form of oil painting.

Where the exhibit falls short is on the specific theme of conflict and reconciliation. It is a difficult topic to present in any format. The commissioners of the exhibition hoped that individual stories captured by de la Concha could “paint” a portrait of the community’s collective view. Unfortunately, there is not enough of each story to really see the full arc from conflict to the strategies for reconciliation that each person uses.

In light of this, what we’re reminded of most is the simple fact of common experience. A quote on the wall above one row of portraits sums it up nicely: “Through our shared stories, we understand the universal suffering in our lives as well as the joy.” Or as James Rice puts it during his portrait session, “Everyone has something they’re struggling with. The more we share our stories the more we realize we’re not alone.”